Visions of Heaven and Hell is a three-part 1994 BBC documentary exploring the prospects and terrors of the hi-tech future that was looming on the horizon in the early years of the internet. The film features a who’s who of prominent figures of the era: Silicon Valley titans like Bill Gates, industry-adjacent thought leaders like Howard Rheingold and Esther Dyson, cultural luminaries like David Byrne and William Gibson. The prevailing mood of techno-optimist hype is set off against an eerie score, dizzying montages of global cityscapes, and somber narration by Tilda Swinton.

Around 30 minutes into Visions, a less well-known figure makes an appearance: a wiry, nervous young Englishman by the name of Nick Land, identified only as a philosopher. “The structure of societies, the structure of companies, and the structure of computers,” Land declares, gesturing frenetically, are all “moving away from a top-down structure of a central command system … towards a system that is parallel, that is flat, which is a web and in which change moves from the bottom up.”

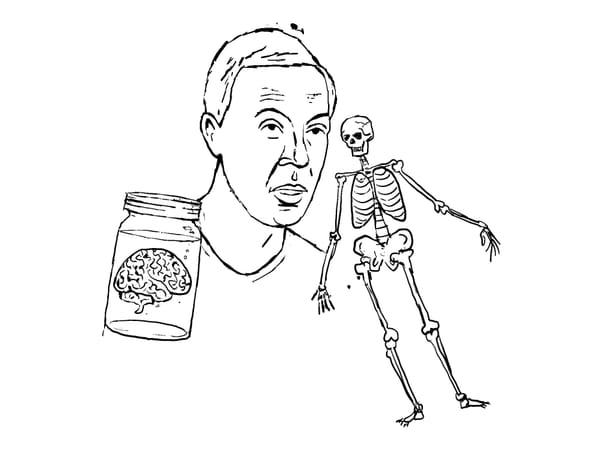

Today, this interview is better remembered for its setting than for what Land said. He appears seated in what seems to be a Victorian-era lab or the back rooms of a natural history museum. Visible behind him are a human skeleton and glass display cases containing rows of brains, some of them cross-sectioned, in vats. If you Google Image search “Nick Land” today, stills from the interview are among the first results that come up.

Over the three decades since his appearance in Visions of Heaven and Hell, Land has become a cult figure. The still from the interview has persisted in meme form because it captures—and has contributed to—the aura that has accumulated around him. The basic substance of what he said—that technology was decentralizing and flattening social structures—wasn’t all that different from what more mainstream Silicon Valley-adjacent voices like Dyson and Rheingold also said in their appearances in Visions, and elsewhere; open any issue of Wired magazine from the period, and you’ll find similar predictions. Land’s backdrop hints at what set him apart. Hovering behind his electric excitement about the digital future was a gothic, death-haunted vision in which the thrill of the new was uncannily tinged with archaism and dread.

His latest turn in the spotlight has revived these themes. It began when, in an appearance on Tucker Carlson’s show a few weeks ago, the podcaster Conrad Flynn named Land as a crucial figure for understanding the current trajectory of tech innovation. By Flynn’s account, the deeper motives behind the current AI boom lie not so much in the drive for profit as in the occult religious convictions and practices of many industry insiders, who seek to use the technology to conjure demons. And Land’s philosophy, Flynn argued, has fed Silicon Valley’s dark AI ambitions. Carlson was intrigued and disturbed.

In an image from the interview that has already been meme-ified, we see Carlson looking in puzzlement at a “numogram” drawn by Land and several collaborators in the late 1990s. This odd graphic might be mistaken for a circuit diagram but, as Flynn explained to Carlson, it is not a technical illustration but a medium of mystical communion with the spirit world: “a system of divination [Land] uses to be in contact with the outside, with what he calls the lemurs.” Carlson interjected: “And lemurs are demons.” Flynn confirmed this: “The word lemurs originally goes back to Roman times. It meant spirit. So these are the spirits that [Land] hears whispering in his ear.” This matters, according to Flynn, because Land’s ideas are “huge in Silicon Valley.”

I spoke to Land over Zoom around a week later and asked him whether he thought his influence within the tech industry was as extensive as Flynn claimed. He said he had “no idea,” and wasn’t in regular contact with anyone there. But as he reminded me, if you take his thinking seriously, it hardly matters. If Flynn and Carlson are worried that “I had this wacky, drug-fueled thought that then got passed into Silicon Valley and became influential,” they’re “not seeing the picture. The picture is completely the other way. That stuff is coming back to us.”

“Land was restating an idea he’s had for over 30 years.”

Land was restating an idea he’s had for over 30 years. Here is how he put it in a 1993 essay called “Machinic Desire”: “What appears to humanity as the history of capitalism is an invasion from the future by an artificial intelligent space that must assemble itself entirely from its enemy’s resources.” Interdimensional lemurs may sound strange; this may be even stranger. That said, it is also familiar from, for one, the Terminator movies—a constant reference point in Land’s earlier work—in which a future artificial intelligence sends emissaries back to the past to secure its own existence.

The fact that his idea echoes a movie plot isn’t incidental. One of Land’s most famous coinages is “hyperstition,” which he defined as “fictions that make themselves real.” They can make themselves real because they are, in fact, anticipatory emanations from the future. This was also the idea behind the lemurs, which first came into Land’s writing by way of William S. Burroughs’s 1987 short story “The Ghost Lemurs of Madagascar,” which in turn, drew on the legend of the lost continent of Lemuria invoked by Madame Blavatsky.

Like capitalism, lemurs come from what Land calls the “Outside,” a realm beyond direct human apprehension in which Kant’s “things in themselves” mingle with Lovecraft’s Old Ones. The Outside is the future, but also the pre-human past of Lemuria and Atlantis. It is beyond our space-time coordinates, so these amount to the same thing. Such ideas may still seem bizarre at first glance, but not much more so than those held by many in the AI industry, increasingly the motor of the global economy. The possibility that we might soon fall under the sway of an alien superintelligence is regularly discussed in mainstream venues and in the highest policy circles. The culture has caught up to Land. Carlson’s baffled contemplation of the numogram is a picture of our shared condition.

Before his latest turn in the public eye, Land was best known for his founding role in two underground schools of thought, both surrounded by an air of enigma, paradox, and danger. The first is accelerationism, which he helped articulate as a philosophy professor at the University of Warwick in the 1990s, the period in which he appeared in Visions of Heaven and Hell. The second is neoreaction, a product of the early 2010s right-wing blogosphere, in which he was an avid participant.

“Accelerationism emerged from a left-wing heresy.”

Accelerationism emerged from a left-wing heresy: the injunction by the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari to “accelerate the process.” Contrary to those who sought to mitigate the disruptive tendencies of advanced capitalism, Deleuze and Guattari argued in their 1972 work of gonzo philosophy Anti-Oedipus that the “true revolutionary path” was to seek their intensification: “to go still further,” as they put it, “in the movement of the market.”

This became the guiding mantra of a line of thinking Land pursued in a series of texts, many written with his Warwick colleague Sadie Plant and the collective he co-founded founded with her in 1995: the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU). The CCRU’s ecstatic vision of “cyberrevolution” took digital technology as a vehicle for reviving the transformative vision of the May 1968 revolution in France, the failure of which was the initial impetus for Deleuze and Guattari’s collaboration.

It would be easy to assume that Land made a hard turn to the political right somewhere between the 1990s and the 2010s, when he reemerged as a neoreactionary blogger residing in Shanghai. But Land never stopped being an accelerationist. In his 1990s writing, the task was to liberate “runaway capitalism” from the “human security system” that was holding it back; that was also true in the 2010s. By then, however, he had come to attribute the inhibition almost exclusively to the progressive left that had become culturally dominant in the West. Taking up his fellow neoreactionary Mencius Moldbug’s term “the Cathedral,” he wrote in a 2013 blog post: “Conceive what is needed to prevent acceleration into a techno-commercial Singularity, and the Cathedral is what it will be.”

What separated Land’s early accelerationist writings from his later neoreactionary texts was the failure of the cyberrevolution he and the CCRU had heralded in the ’90s. Back then, they seemed to think a radical shift toward decentralization, flattening, and liberation from control systems was around the corner. Land told The Guardian’s Jenny Turner in 1995: “The signs indicate that a really big upheaval is coming in 1996,” when we would see a “convergence between computers, broadcasting and telecommunications.” Later, the CCRU saw similar promise in the Y2K event, in which digital technology seemed poised to disrupt the orderly progression of calendrical time itself. What happened instead was the bursting of the dotcom bubble and—worse, from Land’s perspective—the rise of Web 2.0. The Facebook era, for Land, was a time of deep disillusionment. The CCRU had hoped for the digital dissolution of individuality into anonymous cybernetic swarms, but the internet that took shape in the early 2000s sought instead to replicate and ratify conventional offline identity.

The rise of Web 2.0, not coincidentally from his perspective, also marked a left turn in the politics of technology: The dominant culture of the web—and the companies that ran it—was hyper-progressive. In that sense, it is unsurprising that progressivism became Land’s arch-nemesis in the new millennium, and that he aligned himself with an array of similarly disgruntled right-wing bloggers. His most intensive period of neoreactionary blogging activity came after the 2012 US election. The second Obama administration, Land wrote in a 2013 post, marked the zenith of “sacralized progressivism, ivory tower brahminism, academic-media fusion as the exclusive source of recognizable authority, and the absolute identification of governance with public relations.”

In this context, the only remaining possibility was “exit.” This was a term he and other neoreactionaries adapted from the political scientist Albert O. Hirschman to refer to a sort of hi-tech version of Rod Dreher’s “Benedict Option,” which was articulated in the same moment of mid-2010s progressive dominance. Land’s own exile in China, where he believed an accelerative trajectory toward “modernity 2.0” was underway, was a version of this. Other neoreactionaries placed their hopes in seasteading colonies, charter cities, or perhaps Mars—anywhere one might escape the Cathedral’s panopticon. What was to be eschewed, for Land and his fellow travelers in those years, was what Hirschman called “voice”: participation in the political process. As Land wrote in another 2013 blog post, “Our cause is depoliticization … Markets, machines, and monsters might inspire us. Rulers of any kind? Not so much.”

The irony is that something resembling the neoreactionary coalition of the early 2010s is now in close proximity to power thanks to the very thing they dismissed: “voice,” or democracy. The inner circle of the current White House includes factions closely resembling the uneasy bedfellows Land identified in his internet environs back then: Religious conservatives, ethno-nationalists, and “techno-commercialists”—or what is now called the tech right.

Land is aware that his dismissal of politics in the early 2010s looks somewhat ironic in retrospect. When I spoke to him, he told me that since Trump’s return to office, he has been in a “back to the drawing board mode. This isn’t the near future that I was seeing. It’s a shock. I can't pretend that there’s some kind of prophetic vindication in it at all.” That said, he can find ample vindication elsewhere on the contemporary scene—not least, in the recent effort to identify him as a facilitator of rogue AI takeover.

Most of us, if accused in a major public forum of being the mastermind of a demonic conspiracy, might want to correct the record. This hasn’t been Land’s response to the Flynn interview. When I spoke to him, he called Flynn a “master of narrative—really, quite impressive.” He detected in his and Carlson’s effort to spin a tale about where AI is coming from and what it means an instance of a tendency he’s been observing. “Lots of people,” he said, “are getting this stronger sense about things coming together, seeing a peculiar significance in things happening rather than it just being just random episodes of the unfolding of secular history.” What Carlson and Flynn hinted at was that tech entrepreneurs developing AI aren’t simply individuals responding to material incentives, but agents of a “directed historical process.”

The old term for a “directed historical process” is providence—a concept Land explored a few years ago in a series of essays for this magazine. In a recent dialogue with the Russian philosopher Aleksandr Dugin, he brought it up by way of a passage from Goethe’s Faust in which Mephistopheles describes himself as “a portion of that power which always works for evil and always effects the good.” Because Satan is ultimately subordinate to a higher divine will, what might seem to us like the devil’s machinations are always manifestations of a “providential scheme.” Milton’s Paradise Lost, as he noted, points to the same conclusion.

But Land also complicates things by linking this theological model with its secular successor, popularly known as the “Whig interpretation of history,” after the liberal party that dominated British politics in the 18th and 19th centuries. “Whig history” became a derisive term for a classically liberal vision of inexorable scientific, technological, material, and political progress of the sort recently expressed in books like Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of our Nature. Land, too, seeks to vindicate a certain version of Whig history—but with a diabolical twist. Samuel Johnson’s remark that “the first Whig was the devil” should be taken quite seriously, he told Dugin: “In the Anglo-Protestant Whig tradition there is always a complicated relationship to what can crudely be called Satanism.” And it is on this basis that he seeks to defend it.

“God does his work through the devil.”

To make this case, Land cited two early articulations of economic liberalism: Bernard Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees and Adam Smith’s “invisible hand,” both of which argue that “private vices” contribute to public goods. Conventionally understood, the invisible hand is a secular inversion of divine providence: What determines our collective fate is not the transcendental will of a divine being, but the sum total of material incentives working themselves out immanently. And yet this view—Land calls it the “Empty Summit”—isn’t as at odds with a theological one as it might seem. For one, it emerged out of the specific theological matrix of early modern Protestantism, famously described by Max Weber, in which the operations of the market were understood to manifest the otherwise inscrutable logic of divine predestination. The popular contemporary version of this is the “prosperity gospel,” in which God’s favor is revealed by material success. Land’s view, of course, is far darker and more ambiguous. For him, the principle Mandeville and Smith discovered at the foundation of capitalism—that public goods can only be produced by way of private vices—expresses the same theological precept enunciated by Goethe’s Mephistopheles: God does his work through the devil.

If you squint, this is the same idea Land proposed back in 1993 when he said “what appears to humanity as the history of capitalism is an invasion from the future.” Then as now, he claimed that a force outside of historical time—call it God or “the planetary technocapital singularity”—was “guiding the whole desiring-complex towards post-carbon replicator usurpation.” His older account of a “directed historical process” was a mashup of Deleuze and Guattari with Neuromancer, Blade Runner, and the Terminator films. He has now recast it in the terms of Abrahamic religion and English political history.

By Land’s account, the self-improving neural networks that have brought us Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT belong to the Whig tradition: They are technologies defined by decentralization, self-organization, and the “Empty Summit.” Already in 1994’s “Meltdown” he praised the “connectionist or antiformalist AI” of neural nets over its top-down competitors. Today’s AI, he told me, has reached “a sort of eschatological moment of triumphant liberal technology.” And it exploded because its developers embraced a “connectionist, decentralized model. No one knows what’s going on in an LLM. You train it, rather than being able to program it. And it’s completely replaced top-down AI.” It’s in this sense that AI—like laissez-faire economics—has something to do with the devil, but also with providence working through the devil.

Critics of capitalism have often highlighted that system’s Satanic associations. In his 1982 book All that Is Solid Melts Into Air, the radical social theorist Marshall Berman interpreted Goethe’s Faust as an allegory of the deal with the devil made by modern man, who sacrifices his soul in exchange for economic dynamism and worldly pleasures. In a similar vein, in The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America (1980), the Marxist anthropologist Michael Taussig explores the way poor rural wage laborers in Colombia and Bolivia understand their participation in the capitalist economy as a pact with the devil, a source of moral pollution they attempt to expiate through ritual. Taussig interprets this demonological theory as a folk critique of capitalist exploitation. What is unusual in Land’s case is that he underlines the demonic dimensions of capitalism and AI, again, as a proponent of what he calls “paleo-liberalism.”

Now that economic, political, and geopolitical life revolves around the project of building artificial superintelligence, many observers have come around to something like Land’s view: The endpoint of the secular economic logic of neoliberalism—competition, innovation, the pursuit of profit and efficiency—simply is the End Times, much as that was biblically understood. As Land sees it, people—those working in AI, but also AI detractors like Carlson and Flynn—are coming around to his longstanding view that “it’s not like there’s two things going on, where one thing is Silicon Valley building superintelligence, and the other thing is a spiritual realm full of demonic entities.” He added: “As this convergent wave becomes more and more intense, people are gonna really say, look, these can’t be different things.”

Around the same time as his 1994 BBC appearance, Land reviewed Out of Control, one of Silicon Valley’s founding manifestos, by Wired executive editor Kevin Kelly. The book, for Land, exemplified the notion of what he now calls the Empty Summit: “God is dead, and everything happens bottom-up. Top-down control is inhibition.”

The Nietzschean dictum cited by Land might have summarized Kelly’s views on organizational structure, but not his religious convictions. Kelly was a born-again Christian, and his hopes for digital networks were always closely tied to his faith. As a young man backpacking the world in the 1970s, he had experienced a religious conversion on Easter Sunday at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. He came to believe the development of self-organizing networks and self-regulating feedback systems—the subject of his book—replicated the logic of divine creation. “To succeed at all in creating a creative creature,” he wrote, “the creators have to turn over control to the created, just as Yahweh relinquished control to them.” In other words, Kelly saw divine providence and laissez-faire as closely linked. As in Weber’s account of Protestantism, the corollary of God’s absolute sovereignty is a doctrine of non-interference.

“Silicon Valley’s visions of the future have always been infused with religion.”

The tech right is often seen as the most secular wing of the contemporary right. But Silicon Valley’s visions of the future have always been infused with religion. Before Kelly, there was the new media prophet Marshall McLuhan, listed on the Wired masthead in the 1990s as the magazine’s “patron saint.” Although he was circumspect about his faith in his public proclamations, McLuhan viewed electronic communications as a means of realizing the mystical body of Christ. In this, he built on the ideas of the Jesuit mystic Teilhard de Chardin, who theorized that the universe was progressing towards an “Omega Point” of divine unity. This idea anticipated and influenced—via McLuhan among others—the notion of the Singularity that has motivated so many of those working toward artificial superintelligence. Along similar lines, the “Magna Carta for the Knowledge Age,” an ostensibly secular manifesto of the digital revolution written in 1994 by Wired’s Esther Dyson and the futurists Alvin Toffler and George Gilder, proclaimed nothing less than the “overthrow of matter.”

In an earlier moment, messianic proclamations about the digitally connected future were predominantly euphoric, but in recent years they are often far gloomier, not least among those promoting the technology. OpenAI founder Sam Altman summed up the prevailing mood when he infamously declared a few years back: “I think that AI will probably, most likely, sort of lead to the end of the world. But in the meantime, there will be great companies created with serious machine learning.” On the other hand, there are also investor Peter Thiel’s much-discussed recent lectures on the Antichrist, which invert the usual terms of AI safety discussions. The real apocalyptic danger, Thiel argues, is the pursuit of safety itself, which threatens to bring about an authoritarian one-world government that will trap humanity in mediocre stasis.

Such warnings are reminiscent of Land’s account of the “human security system” that was inhibiting technological takeoff—the function he came to attribute to the Cathedral in his neoreactionary period. When we spoke, I asked him what he made of Thiel’s lectures. Noting that Thiel’s outlook is informed by René Girard’s Christian anthropology, he told me: “I don’t think he has biblical time as part of his frame. I think it’s basically still secular historical time.”

It was a remarkable statement. Thiel is a Christian; Land is not, at least in any conventional sense. But Land was telling me Thiel’s understanding of history is insufficiently providential. This was roughly what he said about Carlson’s warnings about AI, too, in his dialogue with Dugin. “The notion that God’s plan for the world can be thrown off course,” he remarked, “if that isn’t heretical, then something is really deeply wrong at the core of your religious conception.” Land’s language has evolved over the past 30 years, but his faith hasn’t wavered.