‘Assassination is not an American practice or habit,” William Henry Seward, the secretary of state under Abraham Lincoln, wrote in dismissing warnings of a plot to kill him and the president during the Civil War, “and one so vicious and so desperate cannot be engrafted into our political system.”

As the Union celebrated Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Seward was confined to his bed, recovering after a fall from a run-away carriage. At around 10 the same night that Lincoln attended a play at Ford’s Theatre, a large, nervous-looking man, with his hat pulled close over his eyes, rang the bell at Seward’s home. He claimed to have medicine that he must administer personally. The doorman let the man in, and pointed him up the stairs. Seward’s son Frederick stopped him near the door to the bedroom, explaining that his father was asleep and not to be disturbed. At this, the man pulled out a pistol. It misfired. He bludgeoned Frederick over the head with his weapon, cracking open his skull. He then pulled out a bowie knife, knocked over Seward’s horrified daughter, who had been sitting at her father’s side, and flung himself on the invalid he had come to kill, slashing at Seward’s face and throat. The last thing Seward remembered hearing was the sound of his daughter’s screams.

Seward survived; the brace on his neck from his earlier injury prevented the knife from severing any arteries. To date, no cabinet official has been killed in office. American Presidents have not been so fortunate. Of the nine presidents elected in the decades between Lincoln and McKinley, three were murdered, an occupational death rate of 33 percent. These postbellum presidents’ odds of getting assassinated were higher than antebellum presidents’ odds of getting re-elected.

Yet all this appalling violence did not disrupt the democratic norm that the president should make himself available to the public he served. Seward’s optimistic faith was qualified by dreadful events, but not repudiated or abandoned. William McKinley was assassinated by a man standing in line to shake his hand. His successor, Theadore Roosevelt, almost as a dare, set the world record for the most handshakes by a head of state in a single day: 8,513 on New Year’s Day, 1907. There were no metal detectors or official invitations to screen these thousands of visitors. The door was open to anyone who showed up reasonably clean and sober. And only a year earlier, a man had been caught walking into Roosevelt’s office with a pen knife up his sleeve. No one loved life more than Roosevelt. But he insisted on living it on his terms.

“Defending America’s tradition of free speech will require following Kirk’s example.”

Something similar could be said of Charlie Kirk, who appeared in public despite death threats, and never shied away from controversy. Defending America’s tradition of free speech will require following Kirk’s example, rather than insisting on a tepid civility.

“Caesar had his Brutus, Charles the First had his Cromwell, and George III may profit by their example,” Patrick Henry declared in the speech that marked the origins of the American Revolution. “If this be treason make the most of it.”

The United States was founded in a violent reaction against an imagined plot to impose tyranny. With the English threat removed, Americans immediately turned their wary suspicions on one other. And they have never stopped hurling monstrous accusations against opponents they tacitly acknowledged as legitimate. There is no more deeply rooted American practice than smearing other Americans as supporters of tyranny—be it “monarchist,” “communist,” or “fascist.” What air is to fire, James Madison wrote, liberty is to “the violence of faction.” But the intemperate freedom with which Americans habitually assail one another has been an unlikely source of resilience, the rhetorical excesses a cathartic outlet for dangerous discontents. To paraphrase Homer Simpson’s toast to alcohol, freedom is the cause of, and solution to, all our problems.

As a matter of abstract logic, it seems reasonable to suppose that when a public official calls his opponents “fascists” or “communists,” he is opening the door to violence. But as Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. once wrote, “a page of history is worth a volume of logic.” Hyperbolic rhetoric is a constant in American political life. It explains a sudden surge in murderous violence about as well as the presence of oxygen explains the outbreak of a fire.

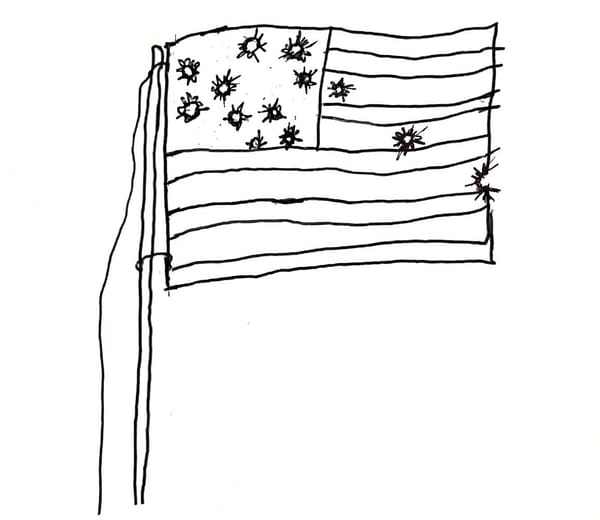

This is no reason to dismiss the threat political violence poses. Charlie Kirk’s assassination was the latest ghastly incident to highlight the dark forces swirling at the foundations of our civil society, surging and receding from one moment to the next. But historical perspective on this intractable problem should discourage a recourse to either simple solutions or radical despair.

Violence in almost every category has declined drastically since the 1960s and 1970s, to say nothing of even earlier eras. The most ominous difference today is not the scale or frequency of violence, but the absence of any unifying consensus to mitigate its corrosive effects.

I will not try to litigate which side is guiltier of the gravest transgressions against the inherited decencies and political freedoms most Americans continue to cherish. I have my own view (it is obviously the left!), but I have stared incredulously at too many incredulous friends to imagine my view is the only one available to reasonable people.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to defend civil discourse in the abstract without an implicit consensus on what speech or conduct is beyond the pale. The principle that no one should be assaulted, criminally prosecuted, or murdered for the mere expression of ideas is necessary but not sufficient.

Basic standards of decency must still be enforced through the informal mechanisms of shame, ostracism, or diminished status. The problem is that these standards are no longer mutually intelligible. It is difficult, even dangerous, to reason sincerely with people who lack a common understanding of what is incendiary and offensive. In that case, respectful discourse among citizens degenerates into the banal platitudes exchanged between diplomats from antagonistic civilizations—signaling not ideas but emotional attitudes of overt respect and implicit fear. The real conversation occurs within separate silos, where uncomprehending grievances fester.

The most pressing danger we face is not anarchic violence or authoritarianism, but an ongoing retreat from the boisterous fray of democratic deliberation. Eventually, political polarization, unchecked by any attempt at thoughtful engagement, will end in stultifying isolation. As the intellectual historian Carl Becker once put it, in the realm of ideas men must find common ground to fight one another.

It would be a grim perversion of Kirk’s legacy if his murder contributes to this lamentable trend. At 31, he exemplified a wholesome delight in political combat among a younger generation that lacked any model for it. In watching videos of him over the past few days, I have been struck less by the substance of his ideas than by his demeanor. He has the poise and tone of one arguing among trusted friends: Cheerful, confident and uninhibited, he provoked in earnest without showing any vulgar or malicious inclination to offend for the mere sake of offending. He had a youthful style that once stood out as singularly American.

The most dangerous response to his murder is not the loathsome online celebration of it. The only novelty in that is the existence of social media magnifying the voices of irresponsible morons and fanatics, who have ever been with us. It is, instead, the decent and well-meaning conceit that political freedom depends on an absolute assurance of safety. If that were true, American democracy would have expired in the same furious passions that brought it to life.

Whether Kirk’s example will become a warning or an inspiration will be determined not by Kirk, or his assassin, but by the generation he joyfully irritated and inspired. T.S. Eliot once wrote, “They constantly try to escape/ From the darkness outside and within/ By dreaming of systems so perfect that no one will need to be good.” There is no substitute for virtue in a republic, and the foremost virtue is and always will be courage.