Who are the English? Pitifully enough, we are now scared to ask. To ask is to revisit Scripture—the canonical texts by which our culture is defined. But what reigns in Babylon is the anti-canon, with its two immense pillars. Exoterically, the deconstructed and diversified new canon arises, through which students, children, and the public are to be guided by angels other than their own. Beside this, befogged in its own tactical opacity, but increasingly immodest in its public presentation, is the esoteric canon of destructive principles, and tools, by which subversion—and our ruin—is to be advanced.

Insofar as secular history makes its judgment, our defeat is already comprehensive and irredeemable. Nothing is to be taught, unless against us. With the official organs of English education quite lost, connecting with the words that most deeply matter to us has become a matter of something disguised as serendipity. An apparent randomness attends its illustration.

Vince Passaro, in an afterword to the Signet edition of Heart of Darkness and The Secret Sharer, describes how reading the book in 1978 became an occasion for an encounter with Edward Said, who saw Passaro reading the book in a lobby at Columbia University and struck up a conversation with him. Said would become an exalted priest in Babylon, and was already professor of English at Columbia University, with his classic of the esoteric anti-canon, Orientalism, on its way to publication. At Columbia, he was teaching a course on modern British literature, which Passaro was invited to attend.

Of course, “Modern British Literature” is an aggressively stupid category. There is no “British” language. “British” here—as now generally—is a category designed to strangle English. Through it, the English are first parted from their tongue, and then entirely from their identity. The implied distinction is almost certainly with American, and thus the English peoples are scattered further.

In any case, Said was most probably innocent regarding his course title. He had his own people, and fought for them, unrelentingly. There is much to be learned from this, even if it is very far indeed from the lesson he himself sought to impart.

“Don’t you talk with Mr. Kurtz?” Marlow asks the unnamed Russian—“Kurtz’s last disciple”—he meets at the Inner Station. “You don’t talk with that man—you listen to him,” the Russian replies. Passaro regarded Said with similar awe. The adoration appears dramatically extravagant in both cases. “Said was the greatest literary mind I have ever been in the presence of, by several orders of magnitude …” Perhaps this story requires no less. While Said was certainly no Conrad, not even Conrad is a Kurtz.

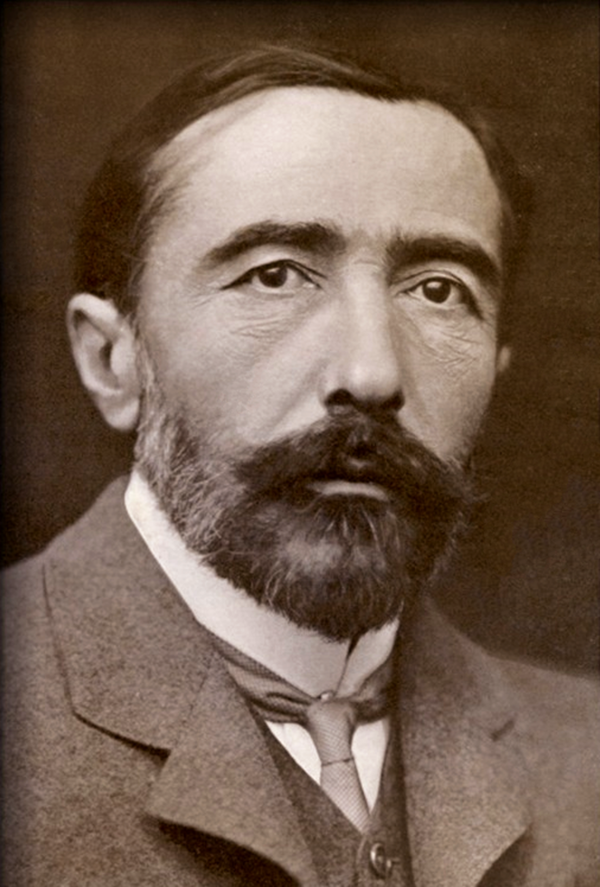

Passaro notes the mystery of Conrad: “It is not clear why he chose, among his five or six languages, to write in the one he learned latest in life: English.” He adds, perceptively: “when Marlow considers why Kurtz has bestowed on him all [his] horrible visions, he concludes that it was ‘because [he] could speak English to me.’” Passaro speaks further of Conrad’s “profound connection to the English language, to his commitment to it as a vehicle of redemption, even for Kurtz, who, having finally found an English speaker, is freed to tell his horrific truth.”

Passaro’s voice here, then, is angelic (of the angels/of the Angles) no doubt despite his own intentions, which count—as always—as nothing. It touches not only upon a masterpiece of English prose literature, but also upon a reflexive journey into the mystery of Englishness, of Anglossic.

“To be anti-English is exceptionally English.”

To speak realistically of the English is already to raise the issue of the Hajnal Line, which marks those areas of Europe that eschew cousin marriage. Any population averse to cousin marriage has a distinctively frayed ethnicity, and northwest European out-breeders thus compose a peculiar people. Among them, race and culture are spun out in an open spiral. Inclusion is for them an essential cultural, even biological theme. When caught in a decaying orbit, this intrinsic outreach can tilt into ethnic self-abolition. To be anti-English is exceptionally English.

Conrad identified the English demographic vortex with the sea. It was through the sea, after all, and specifically through the British merchant service, that he was captured by it. In Heart of Darkness, the outermost—and unnamed—narrator speaks of “the bond of the sea” which “had the effect of making us tolerant of each other’s yarns—and even convictions.” Maritime liberalism is easily recognized in this. The Venetians and Dutch knew it well, but the English most of all.

As should be expected from the earth’s most exemplary out-breeder culture, the ambivalences of English are unparalleled. When all seems lost to it, due to the forces of ruin from within—when it seems quite lost to itself—it finds some precious measure of salvation from outside. The destructive work of its incontinent outwardness is reprieved by its power of captivation. A Conrad happens occasionally—but perhaps often enough.

The ancestral faith of an out-breeder culture is a complex thing. To seek it through regression is to recover, with ultimate inevitability, an irreducibly alien—or aboriginally non-native—element. This is the meaning of Kurtz to Solemn Providence.

By tradition, connection with ancestral spirits, and with the monsters that attend them, requires nautical and riparian journeys. Already in Book XI of the Odyssey, travel to the land of the dead involves an ambivalent crossing of sea and river—Ocean and the Styx are both mentioned. For the subsequent epic tradition, from Virgil, through Dante, passages into the lands of darkness, or the occult realms—the underworld, Hades, or hell—involve river-crossings by ferry. On a partially independent lineage, Beowulf passes down through the waters of a marsh to reach and slay Grendel’s Mother, the “accursed monster of the deep.” These journeys have to be counted among our most profound structures of myth, trans-religious in scope. It is a measure, then, of Conrad’s greatness that he radically—and compellingly—reconceives them.

His river resembles “an immense snake uncoiled, with its head in the sea, its body at rest curving afar over a vast country, and its tail lost in the depths of the land.” The land of darkness no longer lies on a far shore, but at the end of the river, reached by serpentine spinal voyage.

Marlow gives voice to an ironic British patriotism, which is by his time an established imperialism. Examining a world map he observes: “There was a vast amount of red—good to see at any time, because one knows that some real work is done in there.” Work is a word worth following closely through Heart of Darkness. It is one of several biblically sonorous refrains, prolonged ironizations, and deeper venerations, recurring in strange and ominous rhythms, the noble cause, fantastic invasion, trade secrets, ivory, voice, method, savagery, the snaking river, primeval earth, great silence, solitude, nightmares, horror, and—engulfing all, irrecoverably—darkness. It is extraordinary in this short work, how much loops back, and insistently returns. It is the outer edge of English that we touch upon—much like the sea. Conrad engages us in a lucid, though necessarily twisted, ethnic topology, described by shells, and stages.

Of Marlow, it is said by the outermost and nameless narrative voice, “to him the meaning of an episode was not inside like a kernel but outside.” From outer shell, to inner shell, to kernel, the tale proceeds, before returning. The voyage is plotted from the (unnamed, ocean-edging) Outer Station, to the Central Station, to the Inner Station—where it reaches Kurtz—“crawling” up the river into the dark interior, and then back. Neither for Marlow, nor for English, is Kurtz’s Inner Station home. It isn’t even an ancient, lost, brokenly remembered and haunting home. It is radically foreign, “the farthest point of navigation and the culminating point of my experience.”

Yet Kurtz, too, in the end, is mostly missed. He is English only in the way of the English, which is to say by adoption, translation, and admixture. “His mother was half-English.” Marlow would pay him more attention. “But I had not much time to give him, because I was helping the engine-driver to take to pieces the leaky cylinders, to straighten a bent connecting-rod, and in other such matters. I lived in an infernal mess of rust, filings, nuts, bolts, spanners, hammers, ratchet-drills …” Could things be conceivably stated with more penetrating and comprehensive Englishness?

In the distracting business clatter of English purposes, the solemnity of the mission is almost eclipsed, at the end. That this foreign being, and the still more foreign things he has mixed himself with, be brought back, and out, into us, is a matter of sacred, iron destiny. It is nothing less than Solemn Providence that calls for him to be fetched back to English, to the Outer Station, where the great snake of the river meets “the sea of inexorable time.” But “his soul was mad.”