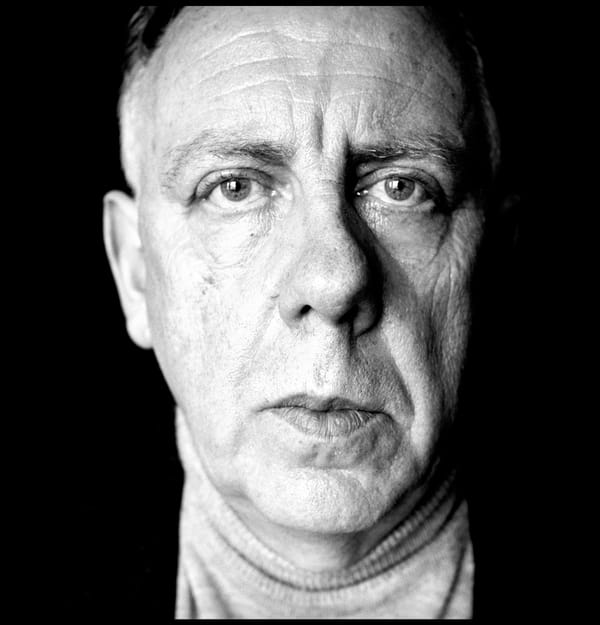

Alasdair MacIntyre (1929-2025) had all the signs of a restless mind. Few philosophers changed their views as much as he did. Thomas Kuhn, in The Structure of Scientific Revolution, described how difficult it is to move from one intellectual paradigm to another. But the truly difficult task is to reflect on one’s failure in accepting the old paradigm, and to give an account of it.

That’s the lonely, humbling task MacIntyre set for himself in the 1970s. Like many of his generation, his paradigm had been Marxism. Born in 1929 in Glasgow, MacIntyre had joined the thriving British postwar left, blending his philosophical pursuits with political activism. It was a hard moment for some Marxists, as postwar prosperity produced the thriving middle class that seemed to falsify once and for all Marx’s theses about the inevitability of a proletarian revolt against the capitalist system.

Not so for MacIntyre. Postwar prosperity showed the defects of excessive historical determinism, but also invited skepticism about attempts to quantify human progress in terms of material prosperity. The ambiguities of the new economy provided an opportunity to ask deeper questions. Above all, they called for an account of how market relations erode the social bonds that uphold healthy communities. Isolated and exposed by the modern economy, people looked to a liberal—and ostensibly neutral—state to protect them from the ravages of the market. But neutrality masked substantive positions. Even more dangerously, the abstract categories liberals latched on to legitimize their government—above all various “rights”—were too open-ended to protect individuals and their communities. Instead, they became ready tools for those who sought to advance their own material interests.

This Marxist paradigm, then, presupposed the failure of two other paradigms: one political, and one moral. Liberalism could not live up to its promises. And while utilitarianism—the pursuit of the greatest happiness for the greatest number—provided a neat axiom to measure and resolve all human problems, MacIntyre, unlike most intellectuals of his time, was never seduced by its solutions. Like another dissident philosopher, Elizabeth Anscombe, he had spotted that utilitarianism’s repudiation of absolute moral prohibitions could justify any action, however intrinsically repugnant.

It was on those moral terms that MacIntyre saw how the methods of Marxism floundered. It accepted too many sacrifices on the altar of History. Identifying the brutality of Stalinism before the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, MacIntyre reflected on the failures of Marxism without blithely abandoning everything he had believed. Many of MacIntyre’s leftist friends, realizing what utilitarian premises legitimated, casually replaced Marxist-inflected utilitarian morality with liberal morality. Stalinism was wrong because we have rights; the rights derided as bourgeois five minutes before the Hungarian Revolution suddenly became sacrosanct, baptized with the authority of neo-Kantianism. This, for MacIntyre, was too much, sheer intellectual sloth.

MacIntyre’s most important essay series from the late 1950s, “Notes from the Moral Wilderness,” is a philosophical cri-de-coeur reckoning with the defects of Marxism, undertaken without abandoning his prior conviction that liberalism and capitalism were likewise failures. One needed a system capable of identifying that failure. Going in and out of various left-wing circles and movements, moving from one university to another and to the United States in 1969, it would take him until 1971 to repudiate Marxism as a political project. If Marx was not a reliable guide, who could provide a sounder alternative?

“Aristotle succeeded in providing coherent answers where Marxism and liberalism had failed.”

By the late 1970s, MacIntyre had come up with what was for a British-educated, revolution-endorsing philosopher a stunning answer: Aristotle. More than just invoking a long dead thinker as an authority, MacIntyre asserted that Aristotle succeeded in providing coherent answers where Marxism and liberalism had failed.

In After Virtue (1981), MacIntyre outlined the core theses of this Aristotelian paradigm. The pursuit of the good had to be exercised in a social context. Moral philosophy, he wrote, “characteristically presupposes a sociology.” Human beings discover the good together, in practice-based communities, by cultivating in common the qualities of mind and character—the virtues—necessary to achieve the good. The school of moral philosophy known as virtue ethics had already been exploring similar arguments, but MacIntyre went much further by sketching a picture of a healthy society as a whole, which also implied a powerful critique of where societies go awry.

In After Virtue, MacIntyre distinguished practices from institutions. Practices are the sites where human beings discover the good internal to a practice that helps achieve the human good. I learn to play chess well by mastering the strategies required to win the game; these are goods internal to the practice. Institutions are the sites where goods external to the practice, such as money, prestige, and power, are used and achieved. These external goods and the institutions arranged around them are certainly useful; someone might incentivize me to play chess well by offering me prizes. Institutions are needed to sustain practices across time. But MacIntyre stresses that though institutions can be confused with the human good, they are not the human good.

It is difficult, if not often impossible to have such practice-based communities and institutions today, MacIntyre argues. We don’t know how to achieve the human good anymore. To keep the chess analogy, we now live in a world where we lack agreement on what the rules of the game are. Worse, those of us who think that we know what the rules of chess are and the strategies required to win it really have no idea. Imagine that half a generation is convinced that all the pieces move the same way, and the other half think that the only opening move permitted in chess is 1. e4 e5. This only begins to convey the catastrophic scale of what has been lost in our moral discourse, and the intractable character of our moral disagreements.

We ended up in this position, MacIntyre argues, because of modern liberal individualism, which defines the human being as essentially constituted by his autonomy. It assumes an individualist society of autonomous agents, and the moral theory it tries to build upon that assumption is one whereby a human being legislates moral rules for himself as the moral law. This idea—a Kantian one—stems from the Enlightenment project.

MacIntyre was not the first to attack neo-Kantianism, but his ingenious argument was to show what kind of culture this way of thinking produces. When the justification for morality is autonomous choice, society becomes populated with “emotivist” selves. They regard judgments about what is good to be mere expressions of preferences and feelings. They thus use moral concepts to advance their own preferences and feelings. The moral vocabulary of the Enlightenment becomes a ready tool for self-assertion. To advance their own preferences, those with power, status, invoke “utility,” “contract,” and “individual rights.” Far from leading to a classically liberal order, this clash of feelings and anxieties leads to the emergence of therapeutic managerialism.

MacIntyre grasped the irresolvable character of our social conflict while most Westerners were still convinced that we could rediscover some elusive political or economic consensus. MacIntyre explained why that aspiration, so dear to the postwar world, was now impossible. Our position was not the result of a few contingencies, whether a few elections or some other factor. It lay in the way we had organized our whole civilization.

In so arguing, MacIntyre made a rather non-Marxist argument. Ideas had consequences; the history of philosophy explains where we are now. We are not, to borrow a phrase, unburdened by what has been. We are not free to pick and choose from the ideas of the past to suit our desires. Intellectually and practically, we are formed and guided by the past. We are forever indebted to it, beholden to the democracy of the dead. MacIntyre’s repudiation of autonomy was not just a theoretical argument against it or a demonstration of the pernicious social culture it produced. In Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (1988) and Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry (1990), he completed the trilogy begun with After Virtue. These two works demonstrated that the way we think and act is constituted by our history, with the goal of showing the superiority of the Aristotelian paradigm over its contenders.

“We’re dumber than we think we are because we’ve lost more than we realize.”

But After Virtue remained MacIntyre’s most powerful, most jarring book, perhaps because it was the ultimate anti-therapeutic text. The thesis, that we’re dumber than we think we are because we’ve lost more than we realize, is destabilizing. It’s all the more so in a world where conservative certainties of God, nation, and family and progressive certainties of History have fallen away. Yet MacIntyre’s project was never just about destruction. It was an effort to build a new practice of intellectual and moral inquiry, a new paradigm or tradition to better understand the world and change it for the better. But a paradigm, even a correct one, is not guaranteed success. It may remain on the periphery. And as it develops, its practitioners may also come to disagree, dividing into competing camps or schools, each claiming not only interpretative fidelity to the master and his core theses, but also a better capacity to meet new challenges.

MacIntyre was easily one of the most brilliant philosophers the British Isles produced in the 20th century. But his reputation within academic philosophy did not match his achievements. Three forces conspired to marginalize him. The first was the critical response to his conversion to Aristotelianism, then Catholicism. MacIntyre’s critique of the Enlightenment in After Virtue and embrace of Aristotle put him under intense suspicion. By contending that pluralism was the sign of social fragmentation, not something to celebrate, and blaming the Enlightenment project for producing this shattered culture, MacIntyre overturned the tables in the temple of Anglophone postwar philosophy. But because of his fame and reputation, because he had been very much part of the mainstream of Anglo-American philosophy, his critics had to engage with him. However, after his next book, Whose Justice? Which Rationality?, his critics changed tack. Here, this prominent philosopher argued that to really demonstrate its superiority over alternatives, the Aristotelian paradigm needed to be reinforced by Thomism. His critics responded by excommunication.

Martha Nussbaum took to the New York Review of Books to denounce MacIntyre’s revolt from reason. You could perhaps survive in mainstream philosophy as a theist and a Catholic, as Charles Taylor did; but you then had to act as he did and wear your liberalism on your sleeve. MacIntyre was of course not prepared to do that. He was branded as a conservative, a reactionary, and his days in the philosophical mainstream were over.

The second was the dynamic of the liberal-communitarian debate of the 1980s and ’90s, which stemmed from the response to the age’s most important neo-Kantian, John Rawls. This might have been a chance for the mature MacIntyre to take up a distinguished position amongst other Anglo-American eminences, as communitarian arguments echoed MacIntyre’s concerns. The communitarians criticized Rawls’ thought experiment of the original position—the notion of an “unencumbered self” freed from all meaningful social ties, bonds, and relationships. Since MacIntyre had also criticized Rawls, neo-Kantianism, and liberalism for producing atomized individuals, this seemed to put him on the side of Michael Walzer and Michael Sandel, the two most important spokesmen for this position. But the communitarian challenge was designed to foreclose a truly radical alternative. It was one made by liberals for liberals, which absorbed criticisms of Rawls into the autonomy-based framework. Here was a case of a paradigm refusing to acknowledge it was in crisis, and its challengers not really willing to push the point too strongly.

The third was the university system itself. Among academic philosophers, interest in MacIntyre cooled in the 1990s. If interest lingered on, it was often in other departments that were less tied to philosophy’s methodological commitments, such as English literature. Perhaps one of the most ingenious applications of his argument was made by the sociologist James Davison Hunter in his book Culture Wars. MacIntyre’s success in the university system proper was inversely proportional to his success in public intellectual life. After Virtue was one of most widely read philosophy books of the past 40 years, a proper bestseller that has sold over 100,000 copies. But it rarely appears on the syllabus of philosophy courses.

MacIntyre’s thinking was simply too capacious to fit into the normal academic channels. He was one of the last true humanist philosophers, capable of drawing from a huge repertoire of classical learning to say insightful things about old books. He dared to generalize about the past, and if he made mistakes, they were always interesting ones. MacIntyre wrote analytically but thought continentally. Such men just didn’t fit in the compartmentalized academic life of the late 20th century.

What was unique about MacIntyre was that he could give a thoughtful account of why his efforts to launch a new tradition of enquiry, a new paradigm, had failed. In a fragmented moral world, MacIntyre anticipated that the positions of Thomist Aristotelians, notably their pursuit of the highest good that culminated in the beatific vision, would be considered unintelligible. It would not register as good in the liberal institutional order and would scandalize its guardians. Marginalized, the best that Aristotelians could hope for was to build communities that could disrupt the established orders. What would that look like?

Like Hegel, MacIntyre spawned a left-wing school and a right-wing school; as with Hegel, one school is poised to be far more influential than the other, if not necessarily faithful to the master’s every pronouncement. In After Virtue, MacIntyre had described Marxism as an exhausted political tradition. But he seemed to hold out some hopes for its revival. Politics was his weak point, as Pierre Manent observed; the political asides in his writings and talks were often conventional Marxist bromides. He worked hard to ensure the authorized reception of his oeuvre would be “revolutionary Aristotelianism.” This left-MacIntyreanism was designed partially in response to the liberal charges of the 1980s and ’90s, which labelled MacIntyre as a conservative or reactionary. But whatever endorsement and energy MacIntyre lent to it, this project gained little traction, not least because very few leftists were interested in his mature work. MacIntyre’s cool reception from the left vindicated another of his early diagnoses: If faced with a paradigm crisis, the left would rather endorse liberal autonomy than explore other alternatives.

“It is impossible to understand the new postliberal right without discussing Alasdair MacIntyre.”

The most enthusiastic audience for continuing MacIntyre’s tradition of inquiry came from the American right. That’s something that surprised and troubled him, as his own paradigm could not account for that. In MacIntyre’s description of the social culture produced by modern liberal individualism, the left and the right pick various aspects of autonomy and defend it for themselves. Defending marriage, life, and the family but also defending capitalism and the market, the right asserts that individuals possess property rights against their community, religion, or government. Defending sexual freedom while also defending economic statism, the political left asserts that individuals possess privacy rights against their community, religion, or government. Both agree on the importance of individual autonomy, even as they attack social structures from different directions. So in one of his last properly political interventions in 2004, MacIntyre argued that one should not vote for either American political party.

But this was not a definitive statement on the American political landscape; it turned out to be his summary judgment on a dying political moment. Ignored by the left, the MacIntyrean Aristotelian paradigm ended up getting picked up by a new American right that was critical of both capitalism and liberalism. It is impossible to understand the new postliberal right without discussing Alasdair MacIntyre.

There is, to be sure, considerable theoretical distance between MacIntyre himself and these postliberals. MacIntyre himself also tried to put as much personal distance between him and those rightists as he could, such as in his pronounced refusal to read Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option. In short, MacIntyre begat devoted children that he disowned. Whether he was right to do so is a question that MacIntyre’s death does not answer. Nor should it. He helped us see the ruins of our time. What practices we develop to escape them is no longer his concern. These questions trouble us; he can rest in peace.