Twice this year, I found myself at conferences where a familiar question surfaced: Why do women not vote conservative? The tone was not hostile, only puzzled. Conservative women asked it themselves, with a kind of weary civility. But none of the answers seemed to satisfy. Some cited the state’s failure to support both motherhood and career; others blamed the lingering shadow of a conservatism that once sought to tether women to secondary roles.

No one could explain why so many women still turn away from even the most progressive forms of the right. Why do they keep voting for a left that consistently throws them under the bus, prioritizing for instance ideologies that deny biological sex and insist on men’s feelings and desires? The answer is simple, although no one wants to see it: Conservatives offer women performative reverence. Progressives offer equally performative protection. But no one offers women the thing they were once promised: freedom.

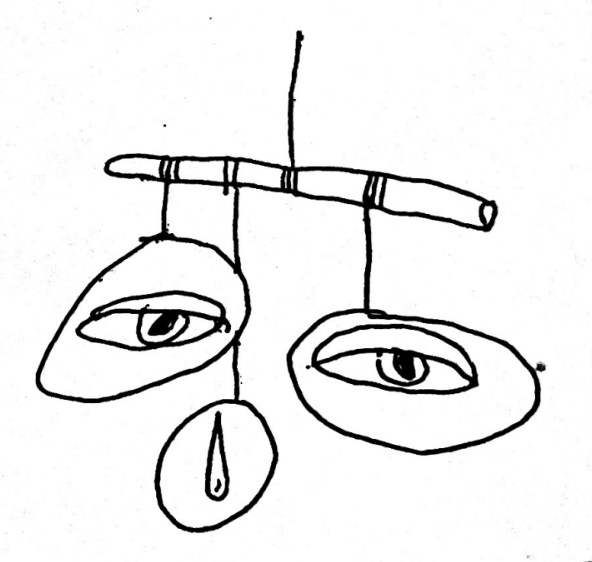

“The woman may be defended, even exalted, but only within the place assigned to her.”

In the United States, women have leaned left for decades, not out of fervent ideological commitment, but through the steady pull of education, work, and shifting social norms. In 2020, Edison exit polls showed that 57 percent of women voted for Joe Biden, compared to 45 percent of men. Across Europe, too, women often favor center-left parties offering tangible supports: childcare, healthcare, material security.

But the dilemma runs far deeper than electoral politics. It touches upon the very essence of what it means to be free. I remain loyal to the feminist promise, however battered or dimmed, of genuine emancipation for women. This vision is not content to merely manage or glorify womanhood, but to transcend its limitations altogether, to be more than a body assigned a function, to move beyond the scripts of sex and tradition, and to claim the dignity of self-authorship. I never wanted merely to be accepted as a woman; I wanted to be free.

The longing for something beyond one's assigned role has not disappeared in me nor, I suspect, in my female friends. And I think it echoes faintly in women’s political leanings, even when the pragmatic reality of political options falls depressingly short.

But for all its progressive posturing, the left, like the right, continues to frame women’s political existence through the lens of womanhood: a role to be honoured, managed, or performed, but never transcended. Women do not lean left because it offers a credible path to emancipation. They do so because the right never even tried, and because the left, despite everything, still carries a faint echo of that promise.

Conservatives do not restrict women uniquely. The right never promised liberation to anyone. Its philosophical roots, in Burkean prudence, de Maistre’s theistic authority, and Schmitt’s decisionism, reject the Enlightenment’s emancipatory project. Freedom is not a matter of self-creation but a disciplined space maintained by stable institutions. The individual is shaped by inherited obligations, not self-chosen ones. Within this architecture, womanhood is a foundational principle. The woman may be defended, even exalted, but only within the place assigned to her.

The right has long supported women whose political power affirms conventional womanhood, exemplified by Phyllis Schlafly’s campaign against the Equal Rights Amendment. Across mainstream conservative politics today, women are encouraged to seek equality with men, but within the same moral framework that conservatism offers to men: duty, hierarchy, continuity, and the primacy of family. British members of parliament like Miriam Cates champion pro-natalist policies, arguing that women’s flourishing lies in embracing family as a civic virtue. The message is consistent: Womanhood is to be honored, but not transcended.

If women lean left, it is not because the left still offers a coherent emancipatory project. It abandoned that project long ago. But it carries the memory of a time when it did. For a time in the twentieth century, the left offered women something transformative. The vote, legal personhood, reproductive autonomy, access to education: These were not attempts to honor femininity but to dissolve it as a political condition. Simone de Beauvoir’s insight remains radical. One is not born, but rather becomes a woman. Womanhood is constructed, imposed, and naturalized as destiny. Feminism’s aim was not to celebrate this identity but to transcend it.

“Emancipation requires solidarity and a shared moral horizon.”

This project was indebted to Hegel. Subjectivity is not given; it is formed through struggle and recognition. For Beauvoir, as for Hegel, freedom is not the absence of structure but the reconciliation of one’s condition with one’s will. Emancipation means overcoming subjection, not managing it.

After the Cold War, it seemed this vision might flourish. The Berlin Wall had fallen; history, we were told, had ended. The ideological scaffolding collapsed. Anything seemed possible. But the moment passed. Judith Butler taught that the self is a performance, and soon the culture began to perform accordingly. Class struggle gave way to pronouns; liberation gave way to HR diversity training. The grand vision of freedom was displaced by debates over who gets the most lines in the next blockbuster.

Why? Because freedom glimpsed after 1989 proved frightening. The collapse of the old order left no moral architecture, only the brutal efficiencies of global capitalism. The dream of emancipation collided with the realities of deindustrialization, inequality, and exhaustion. Into that void marched identity.

In this new dispensation, the political subject became not a bearer of freedom but a bearer of injury. Feminism retreated from the goal of transcending womanhood, seeking instead the recognition of that role. Feminists came to believe that true emancipation could not be achieved and so abandoned the project. Emancipation requires solidarity and a shared moral horizon. Postmodernism offered none of these; it offered instead infinite deconstruction and the comforting cynicism of those who had given up.

As feminism turned inward, the category of woman, which Beauvoir had sought to dissolve, became a site for endless struggles over representation. What had begun as a politics of liberation hardened into a politics of visibility, in which to be seen is to be fixed.

Today, women are invited to succeed, but only as women; to claim rights, but only through the vocabulary of identity. Conservatives seize on the contradictions. Why is misogyny condemned in Western institutions, yet excused when clothed in cultural tolerance? Why is the word woman erased to accommodate trans activism, even as women's rights are eroded? Yet here too, the critique rarely escapes the structure it attacks. The right does not challenge the primacy of womanhood; it seeks to sanctify it. The vision it offers is not one of freedom, but of restored tradition.

“A society that trades emancipation for representation will not remain liberal for long.”

In this, left and right converge. Both insist that women remain political subjects only through the lens of womanhood. There is another path. To be free is not to become a better woman; it is to cease being one, politically. This means refusing to let the realities of biology or lived experience dictate one’s political horizon. It means recovering the possibility of the subject: a person capable not merely of rights, but of obligations freely chosen.

Freedom is not safety. It is the fragile space in which one may choose what binds. That space is now denied by both sides: by the right in its fidelity to traditional hierarchies, by the left in its obsession with recognition. And so women remain politically homeless: voting left because it faintly echoes freedom, rejecting the right because it never promised it.

But this is no longer a question for feminism alone. It is the question upon which the future of political life itself now turns. A society that trades emancipation for representation will not remain liberal for long. What is needed now is not better recognition but the renewal of an emancipatory project. Not better tools of management, but a politics capable once more of asking what obligations we might choose, not as women, not as men, but as subjects.