As the United States approaches its 250th birthday, the most enjoyable way to observe the occasion is with Burr, Gore Vidal’s brilliant novel retelling the history of the founding from the perspective of its most notorious villain. The next year is sure to feature many reverential meditations on the founding, starting with Ken Burns’s new documentary series. And, inevitably, the most pious Americans will use the occasion to condemn the founders for falling short of the democratic ideals they established. Vidal’s Burr offers something different: Aristocratic, 180-proof cynicism toward the whole affair. It won’t do as the main course, but it is guaranteed to make the festivities more fun. And Vidal’s portrayal of Aaron Burr as his novel’s protagonist is more than an entertaining gimmick. Vidal uses it to make a serious point about American democracy and the men who created it.

There are three ways of understanding (and practicing) politics: 1) a neutral process of accommodating conflicting ideals and interests; 2) a struggle between right and wrong, truth and error, the virtuous and the wicked; and 3) a great game, where the score is denominated by power, and the animating, amoral purpose of all who play is to win. Since the Revolution, American politicians have been uniquely adept at the first approach, uniquely passionate about the second, and uniquely pious (or hypocritical) in rejecting any open acknowledgment of the third. Great Americans do not aspire to rule; they burn only with the pure passion to serve.

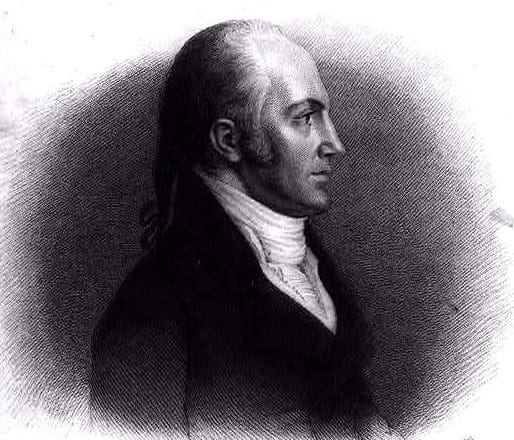

Burr was the great outlier. He made no secret of the fact that he regarded both principles and alliances as mere tactics in the great game. To the other founders, this made him the most dangerous man in the republic. To himself (in Vidal’s telling), this made him the only honest and reasonable man in public life.

“Men who agreed on nothing else agreed he must be stopped.”

No significant American political figure, until Donald Trump, has been accused of so many crimes both lurid and grave. Burr tried to steal an election. He tried to destroy the United States and make himself emperor of a new nation carved out of America and Spain. He was guilty of unspeakable sex crimes. He was not merely corrupt but brazen in his corruption, impervious to shame in a way that made his venality seem almost honest. Yet he commanded popular loyalties that horrified and united his many high-placed enemies. Men who agreed on nothing else agreed he must be stopped, by any means necessary.

The Trump parallels should be obvious. But there was one crucial difference: Burr was stopped. His rivals united successfully, first in blocking his path to the presidency, and then in expelling him from public life in disgrace. The political style he represented was exiled from the nation’s highest office for nearly 250 years.