Immediacy, or the Style of Too Late Capitalism

By Anna Kornbluh

Verso, 240 pages, $24.95

Forty years after the publication of Fredric Jameson’s path-breaking New Left Review essay on “Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,” literature professors continue to beguile suggestible students with the insistence that sleep deprivation, Trumpism, and the entrepreneurial endeavors of the Kardashian family are typical expressions of “late capitalism.” There have been a few attempts to update the periodization, mostly by accentuating the lateness. Hence, a visitor to the website of Verso, the premier left-wing publishing house, will come upon the phrases “very, very late capitalism,” and now “too late capitalism.” The second of these appears in the subtitle of Anna Kornbluh’s new book, Immediacy, which—like any number of Verso titles before it—purports to do for our cultural moment what Jameson did for his.

The odd thing about the undying attachment to the term “late capitalism,” of which Kornbluh’s book is but the latest manifestation, is that it refers to an epoch that ended, by all serious accounts, in the 1970s. For about eight decades, “late capitalism” meant one thing: a centrally administered market economy. When the German economist and historian Werner Sombart coined the term in the introduction to the first volume of his Modern Capitalism in 1902, he even stated that the term should be used interchangeably with “early socialism.” For Sombart, capitalism was an “historical individual” that had passed through the phases of organic life: from the sheepish infancy of early capitalism as it emerged unevenly in feudal Europe, through the reckless and headstrong individualism of 19th-century high capitalism, to the wizened repose of late capitalism, “quieter, more lawful, more rational, in accordance with its advanced age.”

In Sombart’s economic sociology, high capitalism is characterized by the “intensified commercialization of economic life, the debasement of all economic processes into purely commercial transactions.” In late-capitalist society, by contrast, the anonymous domination of the market is brought under control, and the psychological anxieties of a competitive economy subside. One finds “an increase in the number of restrictions until the entire system becomes regulated rather than free,” Sombart wrote, such as “factory legislation, social insurance, price regulation,” as well as “works councils [and] trade agreements.” Additionally, “the status of the wage laborer becomes more like that of a government employee,” and such laborers are met with “the living wage, expressing the same principle as that underlying the salary scale of civil servants; in case of unemployment the worker’s pay continues, and in illness or old age he is pensioned.”

This model of economic evolution dominated the historical consciousness of the modern Western world until the latter half of the 20th century. Theoretical disagreements revolved around the precise dating of the epochal transitions and the normative evaluation of the entire developmental process. Sombart identified the onset of late capitalism with the outbreak of World War I, and he embraced this development. A chauvinist and virulent anti-Semite, he interpreted the war as Germany’s protest against the world-dominating Anglo-American commercial sensibility. During the interwar years of conservative reaction against Weimar liberalism, Sombart extended this interpretation by arguing for the removal of the Jewish merchant spirit from German cultural life to facilitate the emergence of late-capitalist institutions.

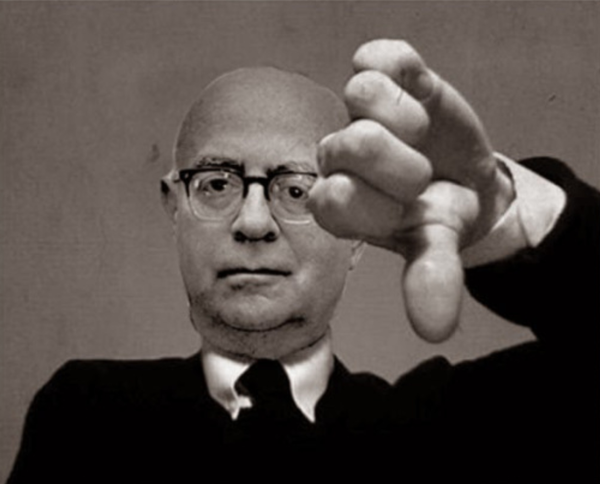

Unsurprisingly, many of the German Jewish intellectuals who were cast into exile in the 1930s criticized Sombart’s conception of late capitalism but without necessarily challenging his developmental schema. The social philosopher Theodor Adorno, for example, saw late capitalism as the logical successor to the 19th-century bourgeois market economy but disparaged this “highly organized and completely centrally administered economy” as “the totalitarian phase of governance.” When Adorno repopularized the term at the April 1968 meeting of the German Sociological Association in his controversial presidential address, “Late Capitalism or Industrial Society?”, his intention was to convince his listeners that this antiquated phrase was still applicable to the postwar European welfare state, notwithstanding its post-capitalistic features. In the months following Adorno’s lecture, the Belgian Trotskyist Ernest Mandel likewise adopted Sombart’s term as the title of his dissertation on postwar economic prosperity—the Fordist era of job security, affordable housing, and public investment in higher education—which was published as Late Capitalism in 1972.

“This early-high-late schema lost its applicability in the 1970s.”

This early-high-late schema lost its applicability in the 1970s, when it became clear that capitalism could respond to crises of growth by rehabilitating the laissez-faire economic policies Sombart had identified with 19th-century high capitalism. Indeed, the masterminds of neoliberal reform weren’t solely motivated by their antipathy to bureaucratic administration and their enthusiasm for free enterprise; they also rejected Sombart’s organicist historical periodization, arguing that the rejection of laissez-faire had been driven by contingent political developments, not an inevitable process of evolution.

If the rise of neoliberalism seemed to undermine the conceptual basis of “late capitalism,” what accounts for its persistence as an organizing concept in contemporary left-wing thought? There is a simple answer. Jameson’s 1984 essay on “The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism” purportedly took its central term from Mandel, establishing continuity between Sombart’s sociology of late capitalism and the exuberant superficiality of postmodernity. And make no mistake: Jameson’s analysis of the stylistic innovations of the 1970s and ’80s was brilliant. But it had nothing to do with late capitalism. Indeed, one year after the publication of this essay, the pugilistic urban theorist Mike Davis excoriated Jameson in the pages of New Left Review, alerting the reader to his conflation of late capitalism with cultural developments that only began after the recession of the 1970s, that is, after late capitalism had already ended. Late capitalism was defined by International Style architecture, Davis argued, not the Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles. We can add Brutalism and Levittown to this architectural counterclaim, along with Kafka’s Castle and Huxley’s Brave New World, Hannah Arendt and Lewis Mumford—these protests against the bureaucratic Leviathan defined the culture of late capitalism.

Davis’s critique should have sounded the death knell of this anachronistic misapplication of Sombart’s periodizing concept. Instead, when Jameson expanded his essay into a monograph in 1991, he dismissed Davis, in a footnote, as a “militant” leftist, thereby inaugurating the ragpicker’s ethos that has dominated academic “theory” ever since. Contemporary scholars of culture are late to the conversation; they rummage through the annals of modern intellectual history as though it were a junkyard of scrap terminology, refurbishing concepts that no longer possess a living connection to reality. They don’t even know what these words once meant.

Kornbluh’s Immediacy is the latest entry in the ever-growing bibliography of “late capitalism.” The occasion for this Jamesonian pastiche is an ongoing dispute within English departments over the usefulness of critical theory for the interpretation of literature and culture. Whereas a small contingent of “post-critical” researchers have been experimenting with interpretive methods that go beyond the paranoid reference to systems of social oppression operating beneath the surface of every text, Kornbluh’s book defends the critic’s ability to cultivate an eye for the calamitous essence of the capitalist totality in every inconspicuous cultural artifact. Adorno called this procedure “social physiognomics,” and Kornbluh positions her project within this tradition.

This would require a comprehensive theory of our present social system, but Kornbluh can’t decide what to call it, when to date its emergence, or how to describe its uniqueness. “Too late capitalism,” she tells us, is “a contradictory moment where the overmuchness of lateness arrests itself.” This slogan competes with “circulation-forward capitalism” and “undead zombie capitalism” to anchor her account of the “zombie phenomenality” of our “petrodepression hellscape.” The basic features of this system include the familiar characteristics of neoliberalism—Kornbluh avoids this concept—like “the gigification of labor,” “just-in-time logistics,” and “attacks on unions, ruthless efficiency standards, expansion of temporary labor,” as well as new features, such as the “instantification of communications,” the “absolutization of time,” and “imperatives for incessant self-facement.” We are witnessing “capitalism’s extremization of its eternal systematic pretext: Things are produced for the purpose of being exchanged.” Obscure references to all three volumes of Marx’s Capital follow.

“Immediacy,” Kornbluh asserts, is the hegemonic style of “too late capitalism.” Insofar as culture always presents itself as immediate, this marquee argument is peculiar, but Kornbluh means to suggest that there is something about “circulation-forward capitalism” that sucks us into the here and now and inhibits our ability to appreciate the social relations constitutive of everyday life. Popular culture exploits this myopia, from immersive art installations to the ubiquity of first-person narration in fiction.

Immediacy is itself a manifestation of this trend. We are encouraged to read the book in a way that feels like mindless scrolling as Kornbluh surveys the cultural landscape with a handful of recurring buzzwords that sound as if they were lifted from a Jacuzzi advertisement. “Whirlpooling presence, gushing feeling, welling current—this is the superfluency of ‘stream style,’” she announces in her analysis of Fleabag, the British comedy series. “Binge is the way of life,” she continues further along, “the constant stream an oceanic jet of immersive flow.” “In the liquid emulsion of these modes,” she writes in her discussion of hybrid literary genres, “in their propensity for indistinct blur, in their churning flow, glides the writerly guise of propulsive circulation: frictionless uptake, fluid exchange, pouring directness, jet speed.”

Much of Immediacy consists of Kornbluh’s pot shots at exemplary products of “too late capitalism.” She reviles Kim Kardashian’s recent collection of selfies, “the burlesque mordancy melding pure profit motive to winking exposé of misogynist image obsession.” Among recent literature, she can’t stand Karl Ove Knausgaard’s “defictionalized omnigeneric fluency,” nor anything written by Maggie Nelson, whose “bounding omnivorism bespeaks immediacy as genre dissolve.” In the domain of moving images, Kornbluh detests streaming video, “the art form par excellence of too late capitalism,” which is “rushing, delugent. We might drown.” She is bored by “the monotonous spill of the sogging stream,” especially that “widening gyre of swirling flush,” AMC’s Better Call Saul. In the world of scholarship, Kornbluh loathes the auto-theory of Paul Preciado and Sara Ahmed, which “liquidates genre in quest of engrossment, repudiates constructions like concepts, trills charisma, and exults sui generis self-springing emanativeness,” not to mention more aphoristic forms of theorizing that “burble with immediacy” by virtue of their “elliptical dance of vaporescence and glut.”

Jameson famously argued that the avant-garde poetry of the 1970s bore a likeness to the dissociated speech of a schizophrenic. Similarly, the mode of contemporary theory practiced by Kornbluh resembles the speech patterns of fluent aphasia, a neurological condition that causes its victims to produce grammatically coherent yet unintelligible sentences that speech pathologists describe as “word salad,” such as: “Medium dissolves, extremes effulge, exposure streams.” Kornbluh’s favorite grammatical construction is an abstract noun followed by a contextually meaningless intransitive verb in a two-word clause, simulating a kind of infantile babbling. “In the extremity of too late capitalism,” she writes, “distance evaporates, thought ebbs, intensity gulps. Whatever.” Page after page, Immediacy discharges these empty phrases in order to disguise the fact that it has nothing to say.

Kornbluh only deviates from this mannered style when referencing current events. “Shit is very bad,” she laments, and we find marbles of this shit scattered throughout the book in the form of hysterical non sequiturs: “One in five students pursues treatment for climate grief.” “The University of Chicago and Temple University have the largest private police forces in the country—and they actually shoot people.” “A small number of hyper-consuming billionaires have irreparably degraded the planet, ergo billions of people will be displaced and killed.” Notice how these allusions to suffering are delivered with an inappropriately blasé intonation, as though reality were something foreign that one learns about in Vox headlines. We are encouraged to believe that, because people are dying and the planet is melting, Marxist literary criticism is urgent, but the relationship between theory and practice remains obscure. Take, for example, Kornbluh’s basic political aspiration: “The masses of people and their social institutions, up to and including the state, must implement transformative solutions like decarbonization, universal care, and vibrant cities that prioritize people over profit, liberate sexuality, and combat racist imperialism with democratic internationalism.” OK. Does roasting Maggie Nelson bring us closer to this desideratum?

“The tragedy of late theory is that it never makes contact with reality.”

The animating principle of Kornbluh’s mode of writing lies in its syncopation of pyrotechnics and posturing: Illusions of serious scholarly activity bar entry to lay readers who feel inadequate to the theorist’s formidable intelligence, but the target reader knows to ignore the smokescreen of neologisms and just vibe with the author’s helpless rejection of our fascist, sexless, ecocidal order. Perhaps Kornbluh is right to suggest that contemporary American consumer culture is shallow, self-absorbed, and politically inconsequential. However, her book will be less informative to readers searching for a sociological diagnosis of this predicament than to readers interested in observing how this superficiality unfolds in the realm of theory. The tragedy of late theory is that it never makes contact with reality.