The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex, and Controversy in the 1980s

By Paul Elie

FSG, 496 pages, $33

In the prologue to his new book The Last Supper, Paul Elie remembers being a young man in the 1980s, “riding the D train with The Village Voice and the Pensées in a black messenger bag.” His reading material was fitting preparation for this book, a masterful survey of pop culture—if a less sure treatment of religious controversy—in the ’80s. His canon is capacious: A-sides and B-sides, major works and minor, early stuff and late, live performances and music videos, installations, short films, feature films, essays, novels, memoirs, biographies. Elie deftly intercuts figures and artifacts in an elaborate chronology of the decade. It is a decade in which, he says, we are still living.

“A soup can is sacralized.”

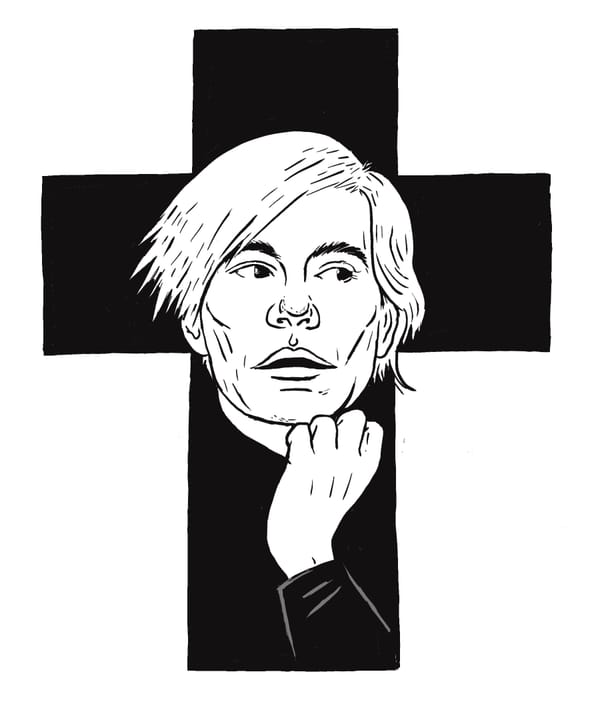

Elie describes the long 1980s as the full flowering of postsecularity—that phase of modernity in which religion rebounds from its losses, but religious authority does not. Religious topics and images suffuse a public that is rife with variance and contestation. The sacred mixes with the profane, if indeed the profane can still be called profane. Beheld by Andy Warhol, a soup can is sacralized, announcing that “presence is everywhere.” If this age has a dogma, it is that the ordinary is extraordinary.

A religious age produces religious art. But the art of the postsecular age, Elie proposes, is “crypto-religious.” Elie uses this term to denote art that “incorporates religious words and images and motifs but expresses something other than conventional belief.” Its styles are many: enigmatic (Bob Dylan, U2), rebellious (Madonna, Sinead O’Connor), sensuous (Prince, Leonard Cohen), ironic (Warhol), esoteric (Brian Eno, Arvo Pärt), blasphemous (Salman Rushdie, Andres Serrano), satanic (Robert Mapplethorpe). In every case, the artist’s religious profession is elusive. Crypto-religious art always “raises the question of what the person who made it believes.”

Elie’s canon encompasses any and every religion, but Catholics, more or less lapsed, are his most numerous and most typical subjects. Elie, of course, is the longtime Catholic correspondent for The New Yorker. But there is a further necessity. Catholicism is the great instance of a doctrinally and culturally thick religion that relaxed during the long 1960s, cutting loose millions of adherents and cutting slack to those who remained, even as its imperious phase lived in memory. So it supplies in spades the raw material of crypto-religious art: a public heritage that can be invoked, evoked, traduced, and remixed by artists who are shaped or exercised by it while disregarding its strictures.

For Elie, crypto-religion confesses what religion always, in truth, has been: a process of personal meaning-making that draws on traditional religion but is not answerable to it. “It makes clear (as if we needed reminding) that the questions at the core of experience can’t be settled through fact or doctrine.” Elie resists not only fixed definitions of faith, but any clear definition of the crypto-religious. Often we suspect that, under cover of crypto-religion, he is lumping artists who have a religious self-understanding with those who merely had a religious upbringing.

Problems arise. For one thing, when we conflate the Catholic (n. a member of the Roman Catholic Church) with the merely Catholic (adj. relating to the Roman Catholic Church), there is no exit. And sometimes you do need to let a guy leave. For instance, James Joyce, whom Elie calls “the vividest example” of a 20th-century “crypto-Catholic” artist, and a godfather of ’80s crypto-religion. Elie says that the 20th-century crypto-Catholics had personal understandings of Catholicism that put them at odds with the official Church. “This led them to express their Catholicism furtively—and cryptically.” The crypto-Catholic cherished a Catholic self-understanding, which he regarded as all the truer for being at odds with the actually existing Catholic Church.

Does this describe Joyce? Undoubtedly he was saturated, like his alter ego Stephen Dedalus, with the religion from which he had exiled himself. But exile presumes borders. Stephen’s “Non serviam,” which quotes Satan’s self-exile from heaven, could be translated for our purposes: “I will forever speak Catholic and nevermore be one.” It evokes the author’s obsession with what he has renounced. This is the deal Joyce struck with the Church, and it is quite different from “I’m staying, but on my own terms.” If Joyce was a Catholic writer, the sense must be adjectival: His novels pertain to Catholicism (preeminently, among many faiths). Whether he was a nounal Catholic, even an eccentric one, is a biographical question that might be settled by his widow’s instruction that he not receive a Catholic funeral. To call Joyce a crypto-Catholic is to conjure his Catholic profession semantically.

“Joyce seems to have viewed the Church as narrow and demanding, the ultimate bitch ex.”

The broader effect is to recruit him to a view of Catholicism as whatever a creative spirit needs or wants it to be. But Joyce seems to have viewed the Church as narrow and demanding, the ultimate bitch ex. In the notion of the crypto-Catholic Joyce, we suspect a desire to claim a great Modernist as a post–Vatican II Catholic liberal avant la lettre. But had he been one, we would not remember him.

In many cases, a valorization of the ordinary is what authenticates an artist’s crypto-religion. Joyce’s Ulysses is “infused … with the Catholic sacramental practice of consecrating ordinary things for sacred purposes.” With this observation Elie is on firm, if well-trodden, ground. The extraordinary ordinary is a soft extension of the doctrine of the Real Presence. Readers of faith-and-literature scholarship may encounter it under the heading of “the sacramental imagination” of Flannery O’Connor or Gerard Manley Hopkins. The concept is Catholic-ish, but also an off-ramp. To the extent that it elides the difference between profane and sacred, between presence and Real Presence, it obviates dogmatic and disciplinary claims. Elie writes: “Ordinary life is full of meaning, present from moment to moment. … Firm beliefs have softened, rituals been left behind, faith in a personal God thinned out or chipped away—but the sense of a supernatural presence remains.”

Elie offers a brief history of the ordinary. The Protestant Reformation championed the ordinary; the Council of Trent opposed it by holding “the lives of ordinary people … less significant than those of priests and nuns.” The 19th-century revolutionary movements announced “the age of the common man”; Catholic anti-modernism condemned democracy, women’s suffrage, and premarital sex. Vatican II opened the doors to the ordinary with guitar Masses, the elimination of Latin liturgy and altar rails, and the pastoral nullification of strictures against artificial contraception; only weird traditionalists objected. The political meaning of “the ordinary” slides around, but in Elie’s usage it is always laudatory and always antithetical to dogmatism, especially Catholic dogmatism.

Crypto-religious artists affirm the ordinary in extraordinary ways. Warhol had his Brillo boxes. The sub-Warholian artist-nun Corita Kent made a silk screen of Wonder Enriched Bread, “a frank reference to the Eucharist,” which the Vatican II Church was rendering ordinary. Daniel Berrigan, SJ, made his name in the Vietnam Era as an anti-war protestor, destroying draft files with human blood and homemade napalm. Evidently as a matter of course, “he celebrated Mass by consecrating supermarket bread and jug wine, using a coffee cup as a chalice.”

One man’s ordinary is another man’s anomie. In 1897, at the end of the century of revolutions, the sociologist Emile Durkheim described four types of suicide, one of which ensues upon society-wide moral deregulation. When dogmas and stigmas melt into air, clearing the way for “ordinary” modern life, many people will feel that their lives are suddenly without meaning.

The anthropologist Mary Douglas had a similarly illiberal take in the 20th century. After Vatican II, the ancient obligation to abstain from meat on Fridays, a clear and constant and achievable discipline, was replaced by choose-your-own-adventure penance. Catholics were to discern as individuals the particular sacrifices they were being called to make. Might be something new every week! The idea was to make Fridays “ordinary,” and boy did they become ordinary. Today, very few Catholics are aware of their Friday obligation. In the immediate wake of the Council, Douglas observed that the loss of the familiar Friday custom was devastating for … may I call them ordinary Catholics? I mean the great majority, who lack the education or inclination for verbally explicit religious self-scrutiny. People for whom clear standards, disciplines, and identity markers are exceedingly helpful. “Do whatever you want” sounded a lot like “We don’t care what you do,” which in practice meant that their religion had been abolished. Having ceased to observe Fridays, many of them ceased to observe Sundays.

We thus have a partial explanation of why Vatican II, that gentlest of revolutions, which purged nothing but the weird shit nobody wants back, was followed by a calamitous decline in affiliation. And of why churchgoing, like solvency, sobriety, monogamy, life expectancy over 80, and other indices of wellbeing, has become a privilege of the disciplined bourgeoisie. Dogmas and stigmas are the stuff of ordinary people’s ordinary lives.

Elie assumes the emptiness of authority claims, but it is only by resisting or repurposing these claims that his favored religious mode finds any meaning. Martin Scorcese’s 1988 film The Last Temptation of Christ was based on the Nikos Kazantzakis novel in which, as Elie puts it with the expected emphasis, Jesus “dreams of coming down from the cross in order to live as an ordinary man.” The film drew on “historical Jesus” scholarship, which was current at the time. This body of scholarship sought to recover the “Jesus of history,” who was perhaps a very different figure from the “Christ of faith.” Catholics and Protestants objected to the film’s emphasis on the ordinariness of the Second Person of the Trinity. He is indeed a bemused and sullen Messiah, quite apart from the brief but memorable visualization of his impure thoughts about Mary Magdalene.

“The fundamentalists” were bad enough. But “it was the rejection by the Catholic bishops—men who hadn’t seen the film themselves, just taken things on trust from their subordinates—that pushed things over the line,” for Elie no less than Scorcese:

They could have watched the film before dismissing it. They could have gone with their people to the theaters and watched it with them. … They could have taken the controversy as an occasion to affirm the doctrine of the two natures of Christ and urged Catholics to watch the film with that in mind. They could have recognized Scorsese as a Catholic of a kind, one whose search was aligned with current Catholic biblical scholarship and the struggles of ordinary Catholics.

“Also possible is that they would have found The Last Temptation a tedious provocation.”

Also possible is that they would have found The Last Temptation a tedious provocation, which dramatizes the mystery of Christ’s divinity by depriving Christ of attributes of divinity attested by the Gospels. As for “historical Jesus” scholarship, perhaps it had been weighed in the balance. These days, even Elaine Pagels is unable to find that it established much.

Protests in Hollywood made the film controversial but of course did not hinder its distribution. Elie snidely describes the bused-in protestors “returning to the places where their God was not blasphemed and their faith not dishonored.” If all the dogmatists returned to the provinces, whom would the crypto-religious scandalize?

In The Last Supper, religious dogmatists are routinely tagged “conservative” (and once, without irony, “the bad guys”). Their opposite numbers are never denominated “liberal.” They are themselves, the capacious creative people. They are ordinary.

The ACT UP die-in of December 1989 is the last major event that Elie narrates. It deserves its placement as the culmination of the postsecular ’80s, and Elie relates it well. The AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power objected to John Cardinal O’Connor’s dogmatic line on sexual morality, which he maintained while presiding over the Archdiocese of New York’s extensive ministry to AIDS victims. Several thousand protestors converged on St. Patrick’s on a December Sunday, bringing their slogans, flyers, and condoms. During O’Connor’s homily, a few dozen activists fell silently in the aisles as if dead. Finding him unfazed, they began to shout at him. During communion, at least one activist desecrated the Eucharist by breaking a host into pieces and casting the pieces on the floor.

The “pandemonium” at St. Pat’s was all over the news, all across the country. It was denounced by conservatives, of course, but also by most liberals and many gay rights activists. Elie accentuates the positive:

In a sense, it worked for all involved. It made ACT UP a force in AIDS policy. At the same time, the public response to it made clear that … sacred space was still sacred. … A quarter century after Vatican II … it turned out that the presence of Christ in the Eucharist was still “real” for the Catholic populace and still credible in society.

Provocateurs target pieties, and the pieties are enlivened by the assault. This is well observed. But there is another reason why the St. Patrick’s action was more successful than ACT UP joints at, say, the Stock Exchange and the General Post Office. To generate outrage, it is useful to feel outrage. Those seeking to establish the moral urgency of the AIDS crisis could thank the Church for its intransigence. O’Connor, no less than ACT UP, was doing something beyond the pale.

“Dogmatism scandalizes liberalism, at least as much as liberalism scandalizes dogmatism.”

The reciprocal outrages at St. Patrick’s reveal the possibility of dogmatism as an avant-garde mode. Dogmatism scandalizes liberalism, at least as much as liberalism scandalizes dogmatism. No figure in the decade had such a clear understanding of these dynamics as Andy Warhol. He did not seek to distance himself from the Catholicism in which he had been raised, and his continuing practice distinguished him from his collaborators at the Factory, his louche studio. Warhol allowed his Catholicism to inconvenience him—just how far remains a mystery. While recovering from a gunshot wound to the chest in 1968, he vowed to attend Sunday Mass faithfully. He kept his vow (for the most part) as long as he lived. Then there is the legend of his perpetual virginity. If he ever did have sex with a man, he kept it a secret even from his diaries. Elie seems to regard it as plausible that Warhol might have died a virgin, though it seems equally plausible that, at a time when even Robert Mapplethorpe dreaded being called gay by the press, Warhol was just very, very cagey. Though Elie doesn’t mention it, biographers report that Warhol, following the counsel of a priest, always refrained from receiving communion—which suggests both that he had habits he did not care to renounce, and that he regarded those habits as mortally sinful.

Elie summarizes the tantalizing suggestions of a eulogist (speaking at St. Patrick’s, of course): “His indulgence of decadent behavior at the Factory was rooted in compassion for the lost souls who found their way there.” Is that a dogmatist glowering above the turtleneck? Our question about Warhol’s faith—was it for real or just a pose?—is the question that arises any time religion emerges as fashionable, or as part of a scene. Warhol, atypically within his scene, seems to have understood his faith as a set of demands. Perhaps he was sacrificing for style, like a true dandy. Certainly he was performing the “deeply superficial” irony that you can’t make light of what isn’t grave.

If Madonna’s dirty-virgin persona seems so 1984, and The Last Temptation of Christ is an expired outrage, Warhol’s style of faith remains a compelling paradox. It is not specific to its historical moment. Elie proposes that postsecularity is here to stay, that “schematic” religion is a thing of the past. But what if history didn’t end in 1989?

In his epilogue, Elie writes: “A generation of digital natives assumes that the species is ‘wired’ for this, that, and the other behavior—but the seeking of transcendence through devotion to a personal God and service to others isn’t one of them.” This is an odd thing to say about the generation who, according to recent surveys, are helping to halt the decline of religion in America. The Zoomers are not seeking “the ordinary” in religion. They are seeking truth claims and disciplines, dogmas and stigmas. Many are drawn to the forbidden fruit of the Tridentine Mass. Modernity is dotted with recurrences to traditional religion among tone-setting cohorts, from the Oxford Movement to the Decadent Movement to the Dimes Square scene, late of downtown Manhattan. If the return to tradition is perennial in modernity, the postsecular ambience Elie documents may prove unrepeatable. Elie describes the ’80s beautifully, but he misdescribes them as the beginning of our cultural moment. The religious energy of the present age is not crypto-religious—it is trad.