Malaparte: A Biography

By Maurizio Serra

Translated by Stephen Twilley

NYRB, 736 pages, $39.95

Maurizio Serra’s biography of Curzio Malaparte mostly consists of digressions, which is just the right approach in recreating the “mythomaniac, exhibitionist, and serial turn-coat” Kurt Erich Suckert, born in industrial Prato south of Firenze to a well-paid Austrian textile expert. He turned Kurt into Curzio and acquired a surname by reversing Napoleon’s good-side Bonaparte into bad-side Malaparte. Once he in turn was well-paid as a journalist (Mussolini, himself a newspaperman before entering politics, made it into a formal and well-pensioned profession with exceptionally high pay), he lived as a socialite in the highest echelon of interwar Italian society, in which newly rich industrialists like Agnelli of Fiat and Vittorio Cini (whose private island filled with art faces St Mark’s in Venice) mingled with the oldest aristocracy, or at any rate with those princes, barons, and marquises who were still solvent (great wealth was a rarity except for the Sicilian princes whose vast estates were only lost with the 1950 land reform). In Rome, Italy’s aristos gather at their La Caccia club, which still admits no untitled commoners, however rich or famous. He met everyone in the city who mattered, including Mussolini’s son-in-law, the socialite foreign minister Ciano, had an affair with the younger Agnelli’s neglected wife, and talked with everyone about everything, except for his war record.

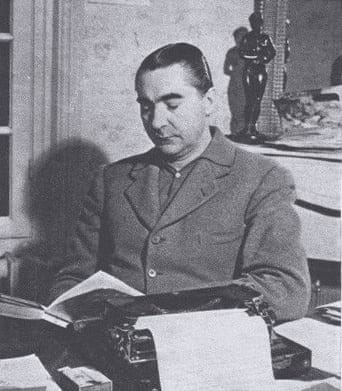

“He met everyone in the city who mattered.”

What Malaparte did not want to advertise was what he did in the Great War: volunteer at age 16 upon the outbreak of war in August 1914 to serve in the just-formed volunteer Garibaldi legion that fought for the French.

When Italy entered the war in 1915, Malaparte—still under age—left the legion to volunteer into the Italian army’s Alpini mountain troops, which fought under oafish generals until the panicked November 1917 collapse of the entire high-mountain Italian front at Caporetto, which forced the British and French to rush reinforcements they could ill afford to spare.

In gratitude for the swift arrival of French troops the year before, in 1918 Malaparte’s unit was sent to help prop up the French front, where his lungs were exposed to German poison gas with ill effects that lasted till he died of lung cancer in 1957. And it was on the French front, with the war about to end, that Malaparte shot his mutilated best friend, who begged him for a bullet as he suffered atrociously with no hope of survival.

Very willing to boast about much else, including his many affairs, Malaparte was reticent about his truly valiant military service because in postwar Italy, everybody and his brother claimed to have been a great hero, and the generals who had insisted on fine cuisine every single day, and stayed far behind the front in order to enjoy it, strutted about Rome like so many tinpot Caesars, claiming credit for the final victory they had not won, and blaming the cowardice of their soldiers for the Caporetto debacle. The generals were mostly from Alpine Italy, where the battle was fought, while many of the troops were conscripted from the coastal south, and utterly unfamiliar with high mountains. They suffered horribly from the arctic cold of the winter.

Malaparte published his own explanation in his provocatively titled first book Viva Caporetto, in which he praised the common soldiers who persevered in the Alpine cold with their inadequate uniforms and unhygienic leggings, under their middle class high-school graduate junior officers who did their duty and died in droves, while the politicians continued to dine out every night in Rome, with the war far, far away. The book was promptly confiscated and pulped, as was a new edition under a different title; it was only fully published in 1980.

But Malaparte’s advance both in journalism—he had joined the Fascist Party and editors loved his incisive prose—and in high society was unstoppable. In his Rome, the mass of “black” aristocrats and descendants of mere papal nephews were outranked by the princes who had veritable palaces they could still staff—like the Orsini, solidly documented since the year 757, and the Colonna, whose descent from Julius Caesar had been derided as pretentious fantasy for more than a thousand years.

It was in the spacious princely salons that Malaparte found material for his often tendentious, mildly subversive but never truly rebellious articles that the Fascist regime could tolerate in a war hero, and which kept him in funds and also in lovers as he plowed his way through the bored wives of high society. He only paused when he reached the summit with Virginia Bourbon del Monte, wife of Edoardo Agnelli, son of Italy’s richest man, the Fiat cofounder Giovanni Agnelli, and mother of Gianni Agnelli, born in 1921, the man who would outrank all other Italians, prime ministers and presidents definitely included, as Italy’s leading public figure from 1955 if not before, until a few years before his death in 2003. He was born too early to be Malaparte’s natural son, but Gianni’s brother and closest associate Umberto was born in 1934…

As Gianni’s advisor for many years, often dining in his vast and art-filled Rome house directly across the street from Italy’s Presidential Palace, or in his villa high above Turin, or in his Park Avenue apartment in Manhattan, whose walls were reserved for more than ten Matisse paintings, I met Umberto many times. I could see no resemblance to Malaparte’s portrait, but by a non-genetic derivation there was a perfect continuity in character with Gianni, who was as recklessly brave as Malaparte had been on the Russian front and more so in fighting the Allies in 1944 in Tunisia, and who competed with Malaparte in conducting amply publicized affairs with the Viking goddess of Dolce Vita fame Anita Ekberg, Rita Hayworth, Linda Christian, the French star Danielle Darrieux, Pamela Churchill, and the widowed Jackie Kennedy—who would later slide way down-market to marry utterly vulgar Onassis—not counting other and younger women he met on the ski slopes where he persisted with his thrice-broken leg, including a 22-year-old American with whom he descended to meet me in a hotel lobby—they had met the day before when waiting in the same ski-lift queue. His wife Marella Caracciolo, a very tall and literally aristocratic beauty, seemed perfectly serene whenever I met her with my own wife—and her brother was the publisher of a major magazine funded by you-know-whom.

By the time Mussolini betrayed his own friends and his Jewish lover on November 17, 1938, by publishing his “race decree” against the Jews to advance his alliance with Hitler that would end with his dead body hanging upside down in Milano’s Piazzale Loreto on April 29, 1945, Malaparte was no longer the convinced fascist of 1922 who had marched on Rome with Mussolini in his bold seizure of power, later ratified by a cowed parliament after the repulsive little king Victor Emmanuel III prevented any use of force by threatening to abdicate (he would deservedly lose his throne in 1947 because of his shameless cowardice).

Malaparte’s first political indiscretion was the 1931 Paris publication of the book Technique du coup d'état, in which he described Hitler’s failed 1923 Munich Putsch, not without noting his womanish character as he strutted about in his uniform, while he described Mussolini as a facile chancer in his own successful March 1922 seizure of power, which Malaparte had been part of. In 1967, when I had to choose the title of a book for an insistent British publisher who had decided that I must become a writer, I came up with Coup D’État while standing at a pub counter between two beers—unashamedly copying Malaparte because there were no techniques in the original, while my own was subtitled A Practical Handbook because it is all about techniques right from the opening line: “Overthrowing governments is not easy.”

Malaparte’s alibi when accused of disloyalty was that he had described the mechanics of seizing power as an antidote to protect against any attempt against Mussolini himself, but his irreverence was undeniable, and had to be punished. He was immediately fired from La Stampa, Agnelli’s Turin newspaper that paid him the equivalent of several contemporary New York Times salaries, and placed under constant surveillance. The latter did not bother Malaparte while his wealthy friends competed in inviting him to stay in their castles, villas, and palaces.

But on Oct. 17, 1933, Malaparte’s surveillance produced its results: He was arrested and imprisoned in Rome’s lugubrious Tiber-side prison Regina Coeli, and expelled from the Fascist Party.

“It was his own intrigue that was his downfall.”

It was his own intrigue that was his downfall: In 1931 he had written a fawning biography of the multi-talented decorated soldier, high Fascist official, and fearless aviation pioneer Italo Balbo, but two years later Malaparte started insinuating that Balbo was plotting against Mussolini, just as the latter was about to appoint him governor of the Italian colony of Libya. Balbo went straight to Mussolini to have Malaparte locked up. After one month in prison he was exiled to the very small island of Lipari with only fishermen for company for a term of five years.

But Malaparte was not bereft of powerful friends, none more so than Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini’s son-in-law and foreign minister. So less than six months later, in the summer of 1934, his place of exile was elevated to elegant Ischia, where he lived in luxury, with friends and lovers coming over on the ferry from Naples, and then to very fashionable Forte dei Marmi. Italy’s richest newspaper then as now, Milano’s Corriere della Sera, even found a way to publish his articles and keep him in funds by having him write under a pseudonym.

Finally the five years were halved to two and a half—a sequence shamelessly summarized by Malaparte as “five years in hell” once Fascism fell and he had to become an instant anti-fascist and fascismo victim. Also in those five much less than hellish years he received permission and found the money to build a remarkable villa on the edge of the rocky cape Massullo of the hyper-fashionable (then as now) island of Capri, one of the places in Italy where it was already impossible to obtain a building permit. Finally he wrote and published in 1940 his most frivolous book when Italy entered the war, Donna come me—“Woman Like Me.”

All frivolity ended when he was fully rehabilitated and made Corriere della Sera war correspondent in Romania, fascist Croatia, German-occupied Ukraine, and Finland, thereby directly experiencing to the full the sheer horror of racial and genocidal war, a much broader, deeper, and more hopeless horror than the murderous artillery and poison gas he had personally experienced in the First War. Many of his articles were not published by the paper but instead collected in his 1943 book The Volga Rises in Europe, then in 1944 Kaputt (death), and finally in the 1949 Skin, that title being an allusion to the open thighs of Neapolitan matrons, women, and teenage girls who were all trying to catch their own spam-bearing GI in 1944 by sitting on the steps of the rising inner-city alleys.

Malaparte’s wartime writings include both a veritable historical document and a fabrication, the former being his interview with Hans Frank, governor general of Hitler’s newly conquered Polish colony, in which the Jews were killed and the Poles were degraded into a servile class (not without the help of countless Polish collaborators). Frank played the elegant and cultured conqueror in his palatial quarters to impress Malaparte, not knowing that Malaparte had already been in Warsaw as a war correspondent in 1919, and could never accept Frank’s confident assertion that the Poles were of a naturally slavish disposition once in firm Aryan hands.

The fabrication, designed to bypass the need for a detailed catalog of horrors, was his interview with Ante Pavelić, head of the Croat puppet state that served the Nazis:

While he spoke, I gazed at a wicker basket on [his] desk. The lid was raised and the basket seemed to be filled with mussels, or shelled oysters, as they are occasionally displayed in the windows of Fortnum and Mason in Piccadilly in London. ‘Are they Dalmatian oysters?’ I asked Pavelic. [He] removed the lid from the basket and revealed the mussels, that slimy and jelly-like mass, and he said, smiling, with that tired good-natured smile of his, ‘It is a present from my loyal Ustashi. Forty pounds of human eyes.’

This highly improbable story was Malaparte’s way to cut to the chase because Pavelić’s militiamen were even more enthusiastic if much less industrial killers than the Germans, eagerly murdering the few local Jews as well as many more Serbs. In post-Communist Croatia I saw them march through Zagreb in triumph, quite a few with their old Ustasha uniforms, that being an occasion to be commemorated with a submachine gun rather than a camera.

A different kind of horror is evoked by Ante Pavelić’s subsequent fate. Having gained favor in the eyes of some high-ranking clerics by killing hundreds of thousands of Orthodox Serbs and forcibly converting as many to Catholicism, Pavelić safely reached Perón’s pro-Nazi Argentina with the help of Catholic institutions acting in the name and under the authority of Pope Pius XII. There Pavelić prospered until a local Serb shot him in 1957, after which he fled to Franco’s Spain to live two more years. (It was my great honor that it fell to me fifty years later to tell the Cardinal Secretary of State Agostino Casaroli that if Pius XII were made a saint, the Jews would remember the names of all concerned—and he was on top of the list—for a least a thousand years.)

It is a matter of personal regret for me that Curzio Malaparte, who immediately saw through the fabrications of every other dictatorial regime, fell for Mao’s China hook, line, and sinker when he visited in 1956, to the point of gifting his Capri house, his only possession, to the Chinese Writers Association, a sorry group destined to be purged, then imprisoned, then starved or even eaten alive if in Zhuang country. Malaparte was ill in Beijing where he received an early version of the 1972 James Reston treatment—that now deservedly forgotten New York Times correspondent underwent emergency surgery while in Beijing with Nixon, was treated in the one and only decent Beijing hospital with foreign-trained doctors that was very strictly reserved for the very top leaders, and reported the story as if he had experienced average Chinese medicine.

Malaparte likewise found a humanist Communist China, a much better alternative to Soviet Communism, and just like the US press with Nixon in 1972, did not even report that Mao’s insistence on the use of human excrement delivered by handcart for use as fertilizer in fields all around Beijing meant that the city smelled like a blocked sewer. (So it was when I arrived four years later.)

Serra won the Prix Goncourt for the French edition of his biography, and his preference for an endless series of digressions (which extend to the medieval origins of the family of a lady our hero bedded perhaps only once) would be frustrating in a life of Napoleon or Mussolini, but is the only possible approach with Malaparte, who at the end threw even Mao’s China into the pot, but whose tale is quintessentially Italian. His only real journey was from hard-working industrial Prato to Rome’s ineradicable frivolity, which makes the important trivial and vice versa.