President Andrew Jackson has always been the favorite historical figure to compare with Donald Trump. The similarities are familiar and recognizable to Trump’s warmest admirers and worst enemies: Jackson was a combative populist, who rallied the nation’s democratic majority to overthrow the rule of a smug, self-dealing elite—or, he was a lawless white supremacist who pandered to the nation’s ugliest prejudices and belligerent impulses.

The usefulness of these comparisons long ago passed the point of diminishing returns. But Trump’s ongoing war against elite academia in general, and Harvard University in particular, has created a new and uncanny parallel to the most dramatic fight in Jackson’s day—the seventh president’s attack on the Second Bank of the United States. The story is worth recounting as the seminal conflict in American history between popular democracy and elite expertise. (The details of Trump’s current war against Harvard can be found in excellent accounts by Gregory Conti here and here and by Steven Pinker in The New York Times.) Two conclusions will emerge from what follows: 1) In attacking and ultimately killing the Bank, Jackson and his supporters destroyed a valuable public institution they did not understand and could not replace, harming the nation’s economy and retarding its development. 2) In arrogantly rejecting even the most reasonable demands for reform, the Bank’s leaders and supporters richly earned its fate.

From the very beginning of the republic, the effort to establish a national bank had occasioned the most embittered and significant controversies over the nature of the federal union. The constitutional dispute depended on whether Congress’s legislative powers were limited to those expressly enumerated (the Constitution did not authorize the creation of a bank) or whether it included implied powers (the power to create a bank was implied in the express power to regulate commerce). It was this issue that first divided Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. But behind the constitutional dispute was an even more fundamental conflict over the nation’s political future. For Hamilton, a national bank was “a political machine of the greatest importance to the State,” an instrument to bind the nation’s business elite to the national government and the key to emulating the British model of a strong fiscal-military power. For Madison and the republicans, the Bank was a tool of corrupt favoritism and aristocratic dominion.

The controversy seemed to vanish, like so many others, in the burst of national patriotism that followed America’s second war with Britain. The original bank’s charter lapsed after 20 years in 1811, just in time for the War of 1812 and the pressing financial demands it created. The government’s financial embarrassments in the war seemed to vindicate the Bank’s necessity. President Madison signed the act creating the Second Bank of the United States in 1816 with hardly a murmur of constitutional protest. The Bank’s architect in the House was John Calhoun. “I seem to be the only person that still cannot find authority for the bank in the constitution of the U.S.” Sen. Nathaniel Macon of North Carolina complained.

The Second Bank of the United States was not an administrative bureaucracy, like the future Federal Reserve, but a privately owned and controlled corporation with a highly profitable relationship to the national government. The government provided one-fifth of the Bank’s $35 million in capital, and appointed one-fifth of its 25 directors. It was the exclusive depository of the public’s funds, which it could use for its own purposes without paying interest. In exchange the Bank paid the government a $1.5 million “bonus” in its first years of operation and performed the government’s banking services without charge. Unless renewed, the Bank’s charter would expire after 20 years, in 1836.

The perception that the constitutional controversy over the Bank had been settled led John Marshall and the Supreme Court to pronounce upon its legitimacy in McCulloch v. Maryland. But Marshall went further than declaring that the Constitution authorized Congress to establish the Bank. His decision also held that, in creating the Bank, Congress implicitly denied the States the power to tax it. To old-school republicans, this seemed to turn the Constitution, and the 10th Amendment, on its head: Congress’s expressly enumerated powers could be extended indefinitely by implication, and the States’ sovereign power to tax property within their jurisdictions could be silently withdrawn by implication.

Marshall thought he was kicking the dead and discredited doctrines of strict construction and state sovereignty into their graves. Instead, he sent them roaring back to life.

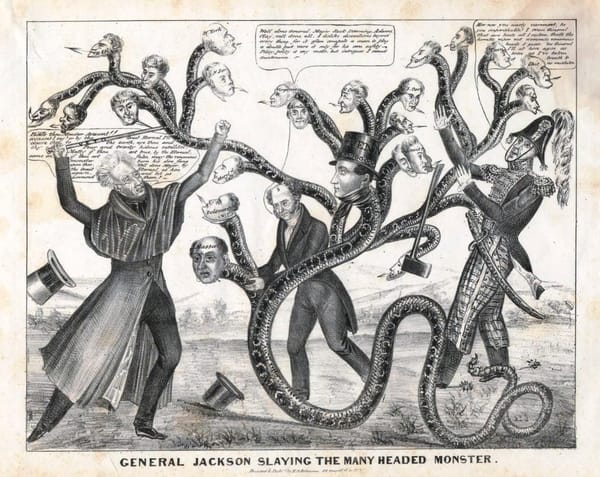

The Bank quickly became a symbol of three combined offenses against democratic principles: It represented aristocratic privilege, unaccountable power, and a usurpation of the reserved rights of the States. For a decade, the Bank’s critics grumbled impotently, their grievances left to fester under an elite national consensus. Then, in President Jackson, the Bank’s neglected critics found their tribune and champion.

Their grievances, however, were either abstract and philosophical or contradictory and misguided. Jackson’s practical objections to the Bank’s functional role in the economy were either untrue or contradictory. He claimed the bank “had failed in the great end of establishing a uniform and sound currency.” This was false. The Bank’s notes were the only paper currency that held the same value in all parts of the country. As Alexis de Tocqueville wrote, “The Bank forms the great monetary bond of the Union just as Congress is the great legislative bond, and the same passions that tend to make the states independent of the central power tend to the destruction of the Bank.”

“Jackson’s true objection was not that the bank had failed but that it had succeeded.”

Jackson’s true objection was not that the bank had failed but that it had succeeded. But this objection, flatly stated, would have divided the Bank’s critics into hostile camps.

His attack on the Bank brought together three antagonistic factions. The first faction—which included Jackson himself—despised all banks and paper currencies as a corrupt swindle. Americans’ distrust of banks reflected hostility toward the financial elites, who seemed to profit from the complex monetary and credit instruments that everyone else relied on, resented and could not comprehend. But it also reflected their bitter experiences with a financial system that was poorly regulated, chaotic, unstable, and teeming with incompetents and crooks.

Gold and silver were reliable as a store of value. But they were inadequate as a medium of exchange. Banks filled the void by issuing paper notes supposedly redeemable in gold or silver. These notes traded at fluctuating discounts from their face value, based on the issuing bank’s reputation for solvency. And the proliferation of paper currencies made counterfeiting exceedingly easy and common. The system thus allowed unscrupulous or sophisticated market actors to cheat those less informed, particularly wage earners and farmers. Hard money advocates attacked the Bank of the United States as the preeminent source of these vices. In fact, it was the one institution that worked to restrain them.

And that was precisely the source of a second popular grievance against the Bank. Indebted farmers, particularly in the capital-starved West, wanted easy credit and cheap money. They championed relief laws that forced creditors to accept at face value depreciated bank notes as payment for debts denominated in gold. The immense resources of the national Bank allowed it to hold substantial notes issued by private banks. (Most of the taxes paid to the government as custom dues were paid in private bank notes.) This financial stake empowered the Bank to act as an informal regulator of state-chartered banks. It could destroy a bank that behaved irresponsibly by forcing it to redeem its notes. The constant pressure it asserted prevented banks from lending too freely or issuing too many notes. Indebted western farmers and wildcat bankers resented this check on their states’ financial autonomy and popular sovereignty.

And finally, many financial rivals, on Wall Street and elsewhere, envied the privileged position of the proud and powerful Bank headquartered in Philadelphia. These rivals saw no reason why only one institution should be the sole depository of public funds.

So to sum it up: The Bank’s hard-money critics were leagued in a crusade with those who resented the bank as a check on the local supply of cheap money; principled critics who denounced the bank as a privileged monopoly were leagued with those eager to expand that monopoly into a privileged oligarchy. But at a high level of abstraction, these flagrant contradictions seemed to disappear.

The president of the Bank, Nicholas Biddle, fully embodied the abstract grievances that united his enemies. No one could deny Biddle’s prodigious abilities. The son of an old and prominent Philadelphia family, he graduated from Princeton at 15, then served as the private secretary to the American minister in Paris. He practiced law, wrote a history of the Lewis and Clark expedition, edited a distinguished literary journal and served in both houses of the Pennsylvania legislature before becoming President of the Bank at age 37 in 1823. An English visitor described Biddle as “the most perfect specimen of an American gentleman that I had yet seen.”

“Biddle managed the Bank with undeniable competence.”

Biddle managed the Bank with undeniable competence and skill, bringing stability and order to the nation’s chaotic banking system. But his exceptional talents and abilities encouraged a characteristic flaw. He was arrogant. He failed to see that he and his Bank depended more on the government’s favor than the government depended on him and his Bank. His and his allies’ conduct throughout the Bank War amounted to a perfect illustration of John Kenneth Galbraith’s observation, “People of privilege will always risk their complete destruction rather than surrender any material part of their advantage.”

“No officer of the Government, from the President downwards, has the least right, the least authority, the least pretense, for interference in the concerns of the bank,” Biddle declared. This was unbelievably rich. The Bank was by law the only place where the government could park the public’s money, money the Bank could lend freely to anyone, on any terms. Biddle seemed to go out of his way to make the anomalous position of the Bank—a privately owned and run institution wielding enormous public power—as flagrant and obnoxious as possible. Those who managed the Bank, he wrote, “should be at all times prepared to execute the orders of the board in direct opposition, if need be, to the personal interests and wishes of the President and every officer of the Government.”

When asked during public testimony whether the Bank had ever “oppressed” any of the State banks, Biddle answered “Never.” But he immediately added, “There are very few banks which might not have been destroyed by an exertion of the powers of the bank.” He thought this demonstrated his high-minded restraint. His critics interpreted it differently.

Though the Bank’s charter was not due to expire until 1836, Jackson’s hostility was obvious from the moment he came into office in 1829. “I do not dislike your bank any more than all banks,” Jackson had told Biddle, a statement that was neither intended nor received as a reassurance.

Biddle and his allies decided to push through legislation rechartering the Bank before Jackson stood for reelection in 1832. Confidently rejecting most reform proposals, the Bank’s friends calculated that Jackson would not dare risk a controversy over the Bank in an election year. It was the first of several spectacular miscalculations.

“It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes,” Jackson declared in his message vetoing the Bank’s charter.

Distinctions in society will always exist under every just government. Equality of talents, of education, or of wealth can not be produced by human institutions. In the full enjoyment of the gifts of Heaven and the fruits of superior industry, economy, and virtue, every man is equally entitled to protection by law; but when the laws undertake to add to these natural and just advantages artificial distinctions, to grant titles, gratuities, and exclusive privileges, to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of society—the farmers, mechanics, and laborers—who have neither the time nor the means of securing like favors to themselves, have a right to complain of the injustice of their Government.

From the Bank’s imposing Greek-revival headquarters on Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street, Biddle dismissed the veto message as mindless demagoguery.

“It has all the fury of a chained panther, biting the bars of its cage,” Biddle wrote of the veto message. “It really is a manifesto of anarchy, such as Murat or Robespierre might have issued to the mob,” he wrote. Edward Everett of Boston thought it was an outrage without precedent in any civilized country. The President’s message appealed “to the worst passions of the uninformed part of the people” turning them against an ancient and vulnerable minority, namely, “the poor against the rich.” It would not be the last time that an objection to government favoritism was interpreted as a malicious and even violent attack on those favored.

In a spectacular misjudgment, Biddle and his allies actually paid to have Jackson’s veto message printed and widely circulated, on the assumption that it obviously exposed him as a vile demagogue. Behind this error was a more fundamental mistake. Biddle and his supporters were so confident in their position, they saw the controversy as an opportunity to defeat Jackson rather than as a grave threat to the Bank’s legitimacy, which depended on its neutrality. It was understandable that Jackson’s enemies would want to exploit the Bank issue for political gain. But only egregious hubris explains the eagerness with which Biddle and the Bank’s sincere friends flung themselves into a war they might have avoided.

The hope that they might secure Jackson’s cooperation by threats and belligerence amounted to an outright delusional misunderstanding of the man they were dealing with. “The bank … is trying to kill me,” Jackson said, “but I will kill it!”

Jackson’s stated objections to the Bank Charter came on two levels, on broad principle and in its practical details. He presented it as a violation of the Constitution and the American principle of equality under the law. But his veto message also cited several specific provisions of the Bank’s charter and discussed each of them at length. Some of these concrete objections were obviously reasonable and just; others were questionable or overblown. But most of them could be accommodated without seriously undermining the Bank’s mission.

To summarize a few key points the Bank’s friends might have conceded without sacrificing justice or self-interest: Jackson correctly pointed out that the renewed charter would dramatically increase the bank’s stock value even after accounting for the annuities it required the bank to pay the government. The Act thus represented an instant gift of millions of dollars to the bank’s private owners, a substantial percentage of whom were foreigners. “For these gratuities to foreigners and to some of our own opulent citizens the act secures no equivalent whatever,” he complained.

Jackson’s objection to the Bank’s privileged status as an exclusive monopoly was based on a provision that prevented the government from chartering additional banks as possible rivals. The Bank’s supporters could have conceded this abstract objection without serious risk that the anti-bank president would want to create more of them.

And finally, the bank charter exempted it not only from punitive and discriminatory state taxation but from all state taxation, creating an unnecessary and unfair advantage over state banks.

The Bank might have escaped a ruinous political battle by yielding on all of these points, allowing Jackson to claim victory without harming the institution. Instead, its defenders chose an all-or-nothing confrontation on the high plane of principle, where there could be no compromise—and where they were bound to lose.

The rhetorical battle that followed will seem familiar to anyone who has observed the hyperbolic accusations that proliferate from and around Trump. Both sides accused the other of tyrannical and corrupt motives. “The nation stands on the very brink of a horrible precipice” the Bank’s defenders cried. Jackson was a backwoods Caesar, determined to overthrow the Republic. In denouncing Jackson as a tyrant, his enemies did not delude themselves into claiming they opposed the wildly popular leader in the name of democracy. They were refreshingly honest in their elitism. “The present contest is nothing more than a war of Numbers against Property,” Edward Everrett wrote.

If Jackson represented the vulgar tyranny of a popular demagogue, the Bank represented the subtler tyranny of organized money. “It is a fixed principle of our political institutions to guard against the unnecessary accumulation of power over persons and property in any hands,” Jackson’s Treasury Secretary wrote. “And no hands are less worthy to be trusted with it than those of a moneyed corporation.”

The Bank was responsible for nearly 20 percent of all personal and business loans in the county; it issued 40 percent of all bank notes in circulation. Its capitalization of $35 million was more than double the national government’s annual spending. The Jacksonians were not exaggerating when they described it as a shadow government controlled by a small clique of elites. One of Jackson’s most outspoken advisers said he preferred “a broken, deranged, and a worthless currency, rather than the ignoble and corrupting tyranny of an irresponsible corporation.”

The Jacksonian obsession with the Bank’s corrupting influence on the nation’s politics was initially misguided. The Bank lent freely to its friends and enemies in Congress. Quoting Jonathan Swift, Biddle observed that “Money is neither Whig nor Tory.” But in attacking Biddle and the Bank, Jackson effectively goaded him into confirming their suspicions.

In the election of 1832, the Bank became nakedly political in wielding its immense resources to defeat Jackson. The Bank spent $80,000 printing campaign materials opposed to Jackson, and Biddle himself spent an additional $20,000—as a share of total GDP, that equates to about $2.5 billion today. Behind this direct financial intervention was the even more formidable influence the Bank wielded over the business community that depended on its favor. Underwriting this power was not the wealth of private citizens but the money of the government Jackson was elected and reelected to run.

After the election, Jackson resolved to begin removing government deposits from the Bank, which represented 50 percent of the Bank’s total deposits. He believed the election vindicated his opposition and that defanging the Bank was necessary to prevent it from buying its salvation. Removal arguably violated the law, which provided that the Treasury Secretary could only remove deposits with an official finding that they were unsafe. The Bank was clearly solvent. So there was no basis for concluding that the funds were at risk. But there was a colorable argument that evidence of the Bank’s political misconduct qualified. At any rate, Jackson had to remove two Treasury Secretaries before he found one who agreed with him.

In removing deposits without any plausible showing against the Bank’s financial position, Jackson’s actions violated the spirit of the law and perhaps the letter as well. And in transferring deposits to friendly state banks, Jackson committed the same sins he claimed to oppose—favoring his partisan friends with control of the public’s money. The only difference was Jackson’s “pet” banks were not as competent or as powerful, for good or ill.

“Biddle met escalation with escalation.”

Once again, Biddle met escalation with escalation. He resolved to use his bank’s existing power to tighten credit and impose a sharp economic downturn. “Nothing but the evidence of suffering abroad will produce any effect in Congress,” he wrote. “All the other banks and all the merchants may break, but the Bank of the United States shall not break.” Once again, Biddle overestimated his position.

In shedding any pretense to political neutrality, the Bank confirmed the President’s judgment of it. “Independently of its misdeeds, the mere power—the bare existence of such a power—is a thing irreconcilable to the nature and spirit of our institutions,” one Jacksonian wrote.

Biddle’s great tragedy was that he completely failed to understand the fears and resentments generated by the unaccountable power he wielded. Nor could he imagine the appeal of the democratic leader he opposed. He described the Jackson administration as “a mere gang of banditti” and Jackson himself as a “frontier Cataline.” The nation, he predicted in a speech to Princeton alumni, cannot “long endure the vulgar dominion of ignorance and profligacy. You will live to see the laws re-established—these banditti will be scourged back to their caverns—the penitentiary will reclaim its fugitives in office, and the only remembrance which history will preserve of them, is the energy with which you resisted and defeated them.”

A year after this prediction, his Bank lost its charter, never to be restored. Not until the Civil War would the national government reestablish a national banking system and currency. Biddle’s bank, renamed under state charter as the United States Bank of Pennsylvania, went bankrupt in 1841. Biddle died three years later, broke and broken.

If the Bank’s allies “were genuinely concerned about sustaining the bank in order to stabilize the US financial system and promote the general welfare,” one financial historian has noted, “then their failure to seek a negotiated compromise in the face of determined presidential opposition was not only impolitic but shortsighted as well.” Unfortunately, he concluded, “Bank supporters were so locked into maintaining the status quo that they utterly failed to weigh properly alternative means of achieving most of their goals.”

That searing judgment comes in a paper in The Business History Review, published in 1987 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Alan M. Garber, the current President of Harvard, would do well to read it carefully.

The sincere friends of elite universities acknowledge that a serious rot has taken hold within these institutions—bloated “diversity, equity, and inclusion” bureaucracies, blatant and unlawful racial discrimination in student admissions and faculty hiring, ideological activism masquerading as academic inquiry, and a hothouse campus climate that sometimes seems as dogmatic and intolerant of dissenting views as a chapter of the John Birch Society. These institutions have forfeited a great deal of public trust and support, and not just among conservatives.

At the same time, it is unclear whether Trump wants to destroy elite universities or reform them. His comments and conduct over the years do not inspire confidence that he cares deeply about the life of the mind or the disinterested pursuit of truth. His own Trump University suggests he sees higher learning the way Jackson saw banks—as a swindle, though Trump of course is not necessarily opposed to a good swindle.

The political attack on elite universities includes a lot of ignorance, bad faith exaggerations, unlawful tactics, and plain envy. These excesses may well serve as an excuse for academic leaders to forget what brought their institutions into this vulnerable position in the first place.

The spirit of Nicholas Biddle is very much alive in the attitude of Lawrence Summers, a man as brilliant and perhaps as arrogant as Jackson’s great nemesis. He cites the tremendous power Harvard possesses as the reason it must resist Trump. And he seems to believe that the immense government privileges the university enjoys, amounting to billions of dollars in public funding and tax exemptions, belong to Harvard by some eternal right indistinguishable from the first principles of free government. In fact, Harvard’s political privileges have always depended on the public’s perception that it stands outside the political arena.

In responding to Trump’s attack, Harvard faces a clear choice: It can seek an accommodation that salvages its reputation and public legitimacy as an apolitical institution without sacrificing its core mission. This will require imagination, courage, and humility. Or it can join the resistance, conflating its fate with the fate of the Republic, the sincere friends of a great and distinguished university with the foes of Donald Trump.

In the middle of the bank war, Jackson went on a national tour, which included Boston—and Harvard. This put the university in a difficult position. Since Harvard had awarded President James Monroe a Doctor of Laws on his visit, the failure to bestow the same honor on Jackson “would be imputed to party spirit,” Harvard governors worried. They thought it best to avoid that imputation, though it scandalized Boston’s brahmin community, Harvard’s most distinguished alumnus most of all. John Quincy Adams raged against his institution’s “disgrace in conferring her highest literary honors upon a barbarian who could not write a sentence of grammar and could hardly spell his own name.” But Harvard’s president stood firm. The American people had elected Jackson their president, he wrote. It was Harvard’s duty to honor the office, not the man.