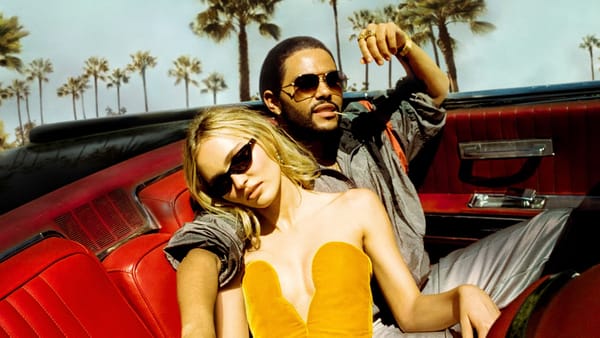

The HBO miniseries The Idol has garnered nearly universal scorn from critics since its pilot episode debuted at the beginning of June. The series, created by Abel “The Weeknd” Tesfaye and starring a shockingly beautiful Lily-Rose Depp as a mid-career pop icon, has been described as “nasty, brutish, much longer than it is, and way, way worse than you’d have anticipated” and “cringe-worthy.” As often occurs, though, this barrage of negative coverage has provided ironic marketing taglines that have made the show a modest hit with audiences, if not critics.

The controversy around The Idol began well before the show’s first episode was released. Perhaps not since Bret Easton Ellis and Paul Schrader disastrously cast a strung-out Lindsay Lohan to star in their collaborative effort, The Canyons, has a Hollywood entertainment product had so much palace intrigue around its production. The Idol’s juicy backstage history was documented in a scandalous Rolling Stone article months before the series premiere, which set the stage for its later critical panning. Initially, Tesfaye had recruited Amy Seimetz, best known for The Girlfriend Experience, to direct the entirety of The Idol. Unhappy with her creative choices, however, Tesfaye fired Seimetz after she had already shot 80 percent of the series. Why? He told reporters that Seimetz brought a “female-centric” perspective to the series that he believed missed the point—all but daring the entertainment media to cancel him.

Tesfaye replaced Seimetz with Sam Levinson, the creator of the dark teen drama Euphoria, to reshoot the entire show and bring it to completion. Hiring Levinson, an auteur with a unique tone and style, amounted to a total creative overhaul of the show. It also heightened the production’s controversy-driven marketing scheme: Levinson faced accusations of cultivating a hostile work environment for the set he ran on Euphoria, and those accusations followed him to The Idol. (The casting of Depp, whose father was recently embroiled in one of the highest-profile and most fraudulent #MeToo cases, in the lead role of Jocelyn could be read as another provocation.)

Levinson is a self-aware enfant terrible who knows what buttons need to be pushed to trigger the right kind of controversy. The Idol’s critics aren’t wrong to be triggered by the show: Embedded in the series is material that directly assaults the fundamental ideological basis of what passes as pop-cultural critique in 2023. The negative reaction to The Idol proves that Generation Woke is not, as midwit conservatives imagine, cavalier about sex. On the contrary, today’s bien-pensant critics are sexual puritans who speak in social-science jargon. Women are expected to be, it seems, sexually empowered, but never to actually do anything sexual—which, in practice, always risks being disempowering due to the inescapable messiness of interpersonal relations.

Levinson and Tesfaye challenge all this head-on in The Idol. In the first sequence of the show, the smoldering Jocelyn, played by Depp, is enthusiastic about posing nude for a shoot. The on-set intimacy coordinator, however, has to point out that she can only pose nude if her team fills out paperwork two weeks ahead of time. His concerns are dismissed by Jocelyn’s label manager (Jane Adams, whose calculating and removed aura evokes that of Cate Blanchett’s Lydia Tár). Later, after Jocelyn meets the androgynous club promoter, pop-music guru, and possible sex cultist Tedros (Tesfaye) and is instantly smitten with him, her best friend and assistant Leia (Rachel Sennot) protests that Tedros “seems so rape-y.” “I like that about him,” purrs Jocelyn.

“Pop music is the ultimate Trojan horse,” Tedros says to Jocelyn while necking backstage at the smooth-talking pimp’s club. This quotation is the show’s mantra, and also functions as a metaphor for Levinson’s creative philosophy. He is masterful at adopting the language and imagery of contemporary pop culture, channeling its addictive and seductive qualities, and deconstructing it with antagonistic thematic content that, in a subtle and elegant manner, challenges the normative thinking that dominates the entertainment industry. With both The Idol and Euphoria before it, Levinson has created products that are entertaining and addictive in the way that social-media generation products tend to be, but also deeper and more emotionally resonant than their glitzy entertainment sheen might initially suggest.

Prestige cinema is practically dead. This year’s Oscar Best Picture winner was Everything Everywhere All At Once, a nearly unwatchable travesty. Last year, Coda won the award; I don’t even know what that is. What vitality remains in the entertainment industry is mostly to be found in streaming series. With shows like Succession, The White Lotus, and Levinson’s projects, HBO has remained at the forefront of creativity in this area by giving creators a long leash.

Levinson has used his good standing with the network to create an aesthetic that hovers between pure pop and the avant-garde. The language of social media and zoomer culture is all over his work: diverse casts, buzzy Red Scare aphorisms, cell-phone and social-media usage interjected constantly into the plot—it’s all there. But there is also a raw brutality in his stories. His characters are abused, violated, and raped. Sadomodernism—defined by Moira Weigel as “denying audiences conventional narrative and subjecting them to pain”—lurks in every frame of Levinson’s projects, even as they are maxed out with contemporary pop excess. He channels the orgiastic violence of Gaspar Noé, the complicated misogyny of Lars Von Trier, the bourgeois misery of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and (with The Idol especially) the fetishistic and maximalist style of Nicolas Winding Refn—all in shows produced for addictive enjoyment.

In a dinner-table scene in The Idol’s third episode, Tedros informs Jocelyn that her friend and creative director Xander (Troye Sivan) has an idea for her upcoming album cover: He suggests they use a recently leaked image of Jocelyn’s face covered in semen. Jocelyn isn’t sure, but her assistant objects strongly, saying: “There are millions of girls who look up to you.” Jocelyn points out that the image is already in circulation, being used against her—so why not assert ownership over it? Leia notes that there was also an outpouring of support for her in response to the leak. “There is no difference between the people making fun of me and the people supporting me,” says Jocelyn. “They’re all capitalizing on me, and they’re all driving people to look it up.”

“We are all feeding the simulacrum, exploiting and being exploited.”

This exchange implicates me, you, and all of us. Fame in the era of social media has abolished the boundaries that separated the entertainer from the entertained. We are all feeding the simulacrum, exploiting and being exploited. This is why The Idol is such a shock. It not only amplifies the commercialization of sex and violence, it makes clear that we are driving it. The performative puritanism of those who object to the show is as empty and hollow as the pop-culture spectacle that we all take part in. The outrage Levinson provokes is just a marketing peg.

It is easy to see Levinson’s project as nothing more than zoomer shlock or, even worse, loathsomely exploitative. But this is exactly why he is an exciting artist: By alienating so many, he forces the few to give themselves over to his vision, and find truth in it. Perhaps that is why The Idol is so upsetting to so many of its viewers: It tells the truth. We all know the entertainment industry that it depicts is disgusting; we know it runs on the exploitation of sexuality and human bodies, and that fame itself is little more than the willingness to be devoured by the mob. As Oscar Wilde said: “The truth is rarely pure and never simple.” Levinson portrays the world as it is—full of greed, addiction, rape, exploitation, manipulation, perversion, alienation, and disconnection—and not as we want it to be.