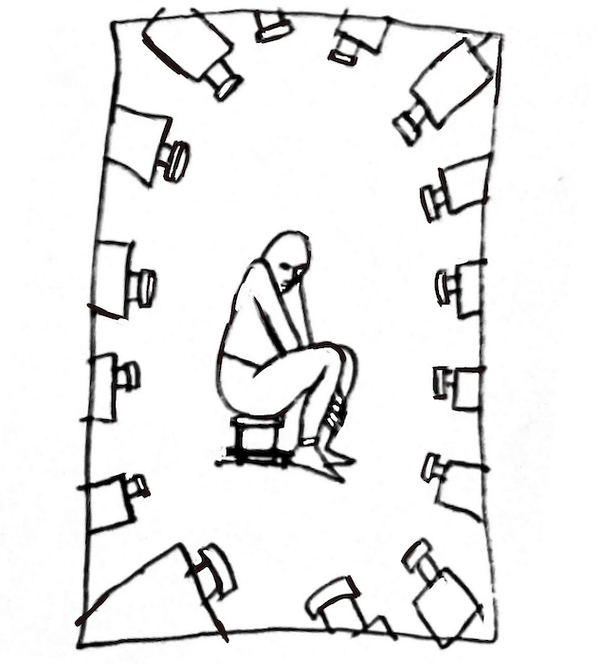

Feminism now defines the Spanish state in the way Catholicism once did. It has its own ministries and budgets and its vocabulary now saturates schools, HR departments, culture, and media. But the result has not been the promised liberation, but a heightening of social control under what might be called “surveillance feminism”—a movement that expands governmental control by casting women as victims, rather than beings capable of exerting independent agency.

A recent controversy of “anti gender-based violence bracelets” shows surveillance feminism at work. Since 2009, judges have paired restraining orders with devices installed on wrists or ankles of alleged abusers who have either been sentenced or whose sentence is pending. Victims are given smartphones which, among other functions, alert the alleged victim if the perpetrator’s device location draws too near.

Earlier this year, a handover between private contractors managing the devices led to the loss of months of location data, potentially leaving victims unprotected and undermining prosecutions. The right has taken the opportunity to attack while the government has gone on the defensive by blaming the company. But no one is asking the more important question: What kind of feminism takes what was once a problem of freedom and translates it into a matter of risk assessments, telecom contracts, dashboards, and tracking devices?

New methods of surveillance have been accompanied by an expanding array of offenses. Legislation known as the “Only Yes Means Yes” law merged “sexual assault” and “sexual abuse” into one crime, with positive consent being the deciding factor. New types of sexual misconduct such as catcalling were criminalized. The result was that women came to be seen as victims, or potential victims, in need of constant supervision and protection.

“The law involves the state in the most intimate aspects of life.”

This law involves the state in the most intimate aspects of life. By requiring positive consent, it implies that women must always know what they want in intimacy and to want it with distinct enthusiasm. The old demand for sexual freedom, it seems, requires an ever growing apparatus of control to ensure that “only yes means yes.”

The scandal surrounding left-wing politician Íñigo Errejón revealed how far Spain’s feminism of “sexual freedom” has turned into surveillance of private life. Accusations against him first appeared on journalist Cristina Fallarás’s Instagram, where anonymous testimonies were posted publicly. Fallarás later published these accounts as Don’t Post My Name, a book presented as testimony to women’s trauma. Actress Elisa Mouliaá then publicly accused Errejón of sexual assault, though her own statements seemed to indicate that the encounter had left her hurt and disillusioned rather than coerced.

Nevertheless, the episode was treated as a case of gender violence and folded into a narrative of systemic misogyny. What emerged was a moral economy in which women’s feelings are taken as proof of wrongdoing and public denunciation replaces due process. The affair showed how the logic of “believing women” extends the therapeutic and carceral state into the most private realms, where even desire and rejection become subjects of collective policing.

Can we have a feminism focused on freedom that doesn’t dissolve into surveillance of the most intimate aspects of everyone’s lives? Such a feminism would concern itself less with the regulation of private life and more with the material conditions that would prevent women from being dependent on abusive men. Unfortunately, the Spanish left has largely neglected the material realities that dominate working-class life and the possibility of uniting around them.