There is an ugly irony in the timing of Norman Podhoretz’s death on December 16. Just two days earlier two Muslims murdered fifteen Jews in a massacre at Australia’s Bondi Beach. In America, anti-Semitism is surging among segments of the young and excessively online right. It also often accompanies the anti-zionism that is rampant on the young left. The new mayor of New York, Zohran Mamdani, may seem like a moderate relative to where the Democratic Party is going.

Meanwhile, the Republican president Podhoretz came around to supporting in his final years, Donald Trump, may be on the verge of waging a regime-change war against the self-described Marxist-Leninist leader of Venezuela, Nicolas Maduro. Podhoretz never regretted his support for the Iraq War. He was the archetypal neoconservative hawk to the finish. He would have been happy to see a war against Maduro—yet the war most important to him, against anti-Semitism, is being lost at home and among America’s allies.

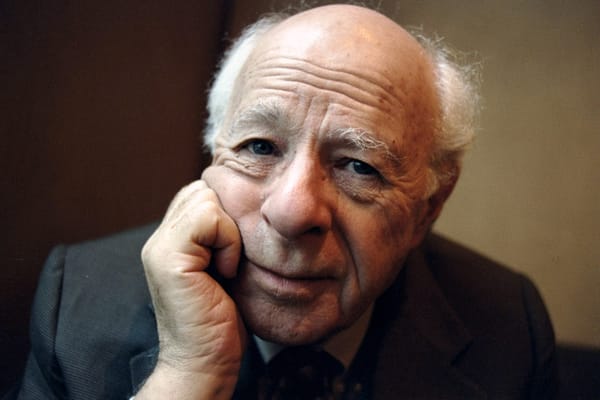

Did Norman Podhoretz’s life end in failure despite the success his foreign-policy views found in the Republican Party?

Podhoretz was tough and smart. He had to be tough in the Brooklyn he was born into in 1930, in what he later referred to as an “integrated neighborhood.” “For a long time I was puzzled to think that Jews were supposed to be rich when the only Jews I knew were poor, and that Negroes were supposed to be persecuted when it was the Negroes who were doing the only persecution I knew about—and doing it, moreover, to me,” he wrote in one of his most famous essays, “My Negro Problem—and Ours.” He recalled “being repeatedly beaten up, robbed, and in general hated, terrorized, and humiliated.”

His family insisted he study Hebrew, even as they were also eager for him to assimilate to (white, gentile) American norms. He made it to Columbia University, then further study at Cambridge in England. He wasn’t of military age during World War II, but after Cambridge he was drafted into the Army from 1953-55, which brought him into extensive contact with Americans from far outside his native milieu. He liked the Middle American soldiers he served alongside. They had a good sense of humor, for one thing.

“He liked the Middle American soldiers he served alongside.”

At the turn of the 21st century Podhoretz would publish a book he called My Love Affair With America. His America was a successful melting pot—the postwar America confident in the righteousness of its moral propositions. These propositions defined the country, and Podhoretz was passionate about fighting for them, first as a liberal, later as a neoconservative. Commentary magazine, which Podhoretz edited for thirty-five years, was his pulpit. When liberals turned skeptical of American values in the 1960s, Podhoretz turned skeptical of liberalism. And as the hard left grew hostile to Jews and Israel, Podhoretz and his fellow neoconservatives turned hostile to the hard left.

That didn’t initially make them friendly to the right, however. The neoconservative “Family,” as Benjamin Balint calls it in Running Commentary, his history of the magazine, “instinctively regarded the the old Right as a brackish cesspool home to anti-Semites, anti-immigration nativists, reactionaries, chauvinists, protectionists, and isolationists.” They “associated conservatives with xenophobes, Dixiecrats, or John Birchers; southern agrarians full of nostalgia for the antebellum South…; rich ‘Rockefeller Republicans’; or Catholic Ivy League National Review types.”

The discomfort with older elements on the right never entirely went away. When Russell Kirk suggested that some neoconservative mistook Tel Aviv for the capital of the United States, in remarks he gave at the Heritage Foundation in 1989, and when Pat Buchanan argued the following year that only the Israeli defense ministry and its “amen corner” in Congress wanted the United States to fight a war against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, Podhoretz branded both as anti-Semites and pressured William F. Buckley Jr. to repudiate them. He wasn’t satisfied by Buckley’s “positively talmudic … whitewash of Russell Kirk,” who may have merited Buckley’s “deepest respect as one of the founding fathers of the contemporary conservative movement” but was nonetheless possessed of an “antisemitic stench.”

Podhoretz likewise found the National Review editor’s criticisms of Buchanan inconsistent: If Buckley labeled Buchanan’s rhetoric anti-Semitic, how could he shirk labeling the man himself the same way? Buckley’s response, reproduced in the concluding chapter of his 1992 book In Search of Anti-Semitism, was to say he found it “odd how much… happier some people are to believe that someone is really evil, when there is the alternative, intellectually respectable, of believing instead that that person misbehaved.”

Although Podhoretz never got the condemnation of Kirk and Buchanan he wanted from Buckley, in other respects the conservative movement of the 1990s and early 2000s largely followed Podhoretz’s lines. He supported NATO’s expansion after the Cold War and a broadly interventionist foreign policy; so did most organs of the conservative movement. In economics, Podhoretz and other neoconservatives came around to a skepticism toward the welfare state and an appreciation of capitalism not much different from the attitudes of mainstream conservatives. Podhoretz thought there was little to distinguish neoconservatives from the rest of the center-right on cultural issues, too—with one crucial exception, immigration.

“The conservative opponents of immigration argue that, unchecked, it will end by destroying the common culture which has given this country its character and held it together in all its diversity. The neoconservatives, myself emphatically included, disagree,” he wrote in a 1996 essay, “Neoconservatism: A Eulogy.” His title alluded to his belief that neoconservatism’s success in remaking the right meant that it “no longer exists as a distinctive phenomenon requiring a special name of its own.”

The neoconservatives had joined the conservative coalition as critics of the left’s anti-Americanism and as ardent anti-Communists in the climactic years of the Cold War—so ardent that Podhoretz at times criticized Ronald Reagan for negotiating with Moscow, conducting a policy of “appeasement by any other name.”

George W. Bush’s foreign policy pleased Podhoretz better than Reagan’s did. He was unstinting in his support for the Iraq War; called for Bush to bomb Iran, too; and in 2008 he published a book making the case for the war on terror as, in the words of his title, World War IV: The Long Struggle Against Islamofascism.

His initial impressions of Donald Trump’s entry into presidential politics were unfavorable. He recounted to The Claremont Review of Books, “I said to my wife: ‘This guy is Buchanan without the anti-Semitism,’ because he was a protectionist, a nativist, and an isolationist. And those were the three pillars of Pat Buchanan’s political philosophy.”

He bristled at Trump’s condemnation of the Iraq War—but was relieved not to hear any strong criticism of Israel. And he came to rethink his views on immigration. He told The Claremont Review of Books in 2019: “What has changed my mind about immigration now—even legal immigration—is that our culture has weakened to the point where it’s no longer attractive enough for people to want to assimilate to, and we don’t insist that they do assimilate.”

“We don’t insist that they do assimilate.”

Norman Podhoretz was a tremendous force as an editor, writer, and prime exponent of neoconservatism. He was also a power as a founder of a dynasty. His son, John Podhoretz, co-founded The Weekly Standard with Fred Barnes and fellow second-generation neoconservative William Kristol, before eventually becoming editor of Commentary himself. Podhoretz’s son-in-law, Elliot Abrams, helped to implement the family’s hawkish policies during stints in government under Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump. Abrams was point man for the maximum pressure campaign aimed at Maduro in the first Trump administration.

The Norman Podhoretz spirit is still alive, even if the man is not. War with Venezuela would be a fulfillment not only of Elliott Abrams’s designs but of his father-in-law’s longtime insistence on the need for force in confronting foreign opponents. But the tragedy of Norman Podhoretz is that foreign policy he advanced is at cross purposes with the struggle against anti-Semitism. Wars bring refugees and waves of migration, including, as a result of America’s wars in the Islamic world, Muslim refugees and migrants to Europe and the United States. Among these migrants are some who perpetrate attacks on Jews; many more are politically hostile to the state of Israel.

The problem is not simply that Muslim immigrants will almost certainly not be friendly toward Israel; it’s also that migrants and refugees from almost anywhere are likely to be less philo-semitic than native-born Americans. Newcomers from Latin America, Asia, India, and Africa do not see Jews or Israel the way white Protestants historically have. Immigration from almost any part of the world begets at best indifference toward Jews and Israel—and at worst, hostility, even to the point of violence.

Yet neoconservatives like Podhoretz have traditionally not only been hawkish in foreign policy, they have been liberal in their immigration policies and hostile to the strongest proponents of immigration restriction: the very paleoconservatives Podhoretz regarded as “nativists” and “xenophobes.” Though Pat Buchanan’s words may have inflamed Podhoretz’s sensitivities, Buchanan’s policies would make the election of figures like Zohran Mamdani or Ilhan Omar far more difficult, if not impossible.

Podhoretz was smart and brave, and while he was stubborn, too, he understood that Donald Trump, for all he may have resembled Pat Buchanan, was the best choice for the safety of Jews and Israel. The hard choice facing neoconservatives today is whether to fight or make friends with the populist right beyond Trump—not with the lunatic fringe, to be sure, but with the heirs to Buchanan. The populist right has its risks. The globalist left, on the other hand, presents the certainty of an America, and wider West, less concerned for Jewish well-being.