On July 18, after declaring “Crypto Week,” President Trump signed into law the GENIUS Act, in a major legislative win for the burgeoning cryptocurrency lobby. Two other bills keenly supported by the industry, the CLARITY Act and the Anti-CBDC Surveillance State Act, also passed the House this month and are now awaiting a vote in the Senate. Together, these bills promise to turn an industry once relegated to the shadows into an important part of the American economy.

When Bitcoin, the first cryptocurrency, was invented, it was promoted as a financial technology that would empower individuals and wrest power away from the state and centralized elites. Just a decade and a half later, those same elites—including the Trump administration and bipartisan majorities in Congress—have embraced cryptocurrencies. But that is because, rather than lifting up ordinary citizens, crypto has become a new means of expanding elite power and wealth.

I was once a Bitcoin true believer. Back in 2013, I sat in a New York University classroom when an eccentric libertarian took to the podium to evangelize the new currency. Drawn to the message, I soon interned at the Bitcoin Center on Wall Street, where I participated in the nascent community. I later hosted events promoting the merits of cryptocurrencies. In 2018, I joined the crypto-focused news site CoinDesk, where I reported on the industry. I also produced a documentary series on cryptocurrencies.

I was never a major player in the ecosystem, but as I met various influential figures and learned more about how crypto really worked, I began to realize that behind the rhetoric of freedom, decentralization, and empowerment was a reality in which a few elites were accumulating immense wealth under false pretenses. As the cryptocurrency economy expanded and evolved over the course of the 2010s, it became hard to ignore how radically the facts diverged from the vision I had been sold. So in 2019, I wrote a Medium post called “Leaving Crypto,” terminated all my crypto-related contracts and collaborations, and sold all my crypto assets.

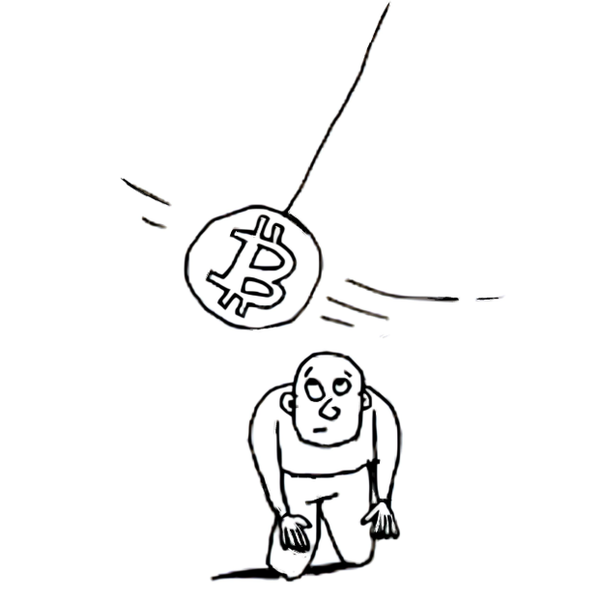

In the years since, the speculative frenzy around cryptocurrencies has only continued to gather steam, to the benefit of private actors who have reaped massive profits from the industry’s growth and are exercising a growing influence over the state. In the process, Bitcoin’s founding goal of fighting unconstrained government spending has been inverted, as crypto is increasingly serving as a means of enabling more deficit spending, an agenda the Trump administration has all but explicitly embraced. Today, crypto is merely the latest ruse to persuade the public to surrender democratic freedom and financial sovereignty to oligarchs.

The story of Bitcoin begins with a simple question: Where does money come from? Around 2008, many were asking this age-old question because of the Global Financial Crisis. Money was plentiful, and then it wasn’t. Why? Mainstream economists had failed to anticipate the crisis, so some turned to unorthodox theories of economics to make sense of what had happened. One of these theories was Austrian economics, a radical anti-statist school of free-market libertarian thought. The Austrians’ answer to the question seems simple enough: Money comes from nature. Simply put, it is (or should be) some form of scarce commodity, like gold; the decentralized market decides which particular commodity is used as money. It follows from these premises that the printing of money by governments artificially corrupts nature. Hence, financial crises like the 2008 crash are the inevitable outcome of this centralized corruption.

“Austrian economics” reached its all-time-high on Google Trends in February of 2009 and its second all-time-high in January of 2012. It was during this period of popularization that Bitcoin was developed and promoted by Satoshi Nakamoto—a pseudonym for a shadowy figure whose identity remains uncertain. Nakamoto led the development of the project from 2008 to 2011, when he mysteriously disappeared.

Bitcoin was digital money that you could send to anyone, anytime, anywhere. No one could control or confiscate it. Its combination of cryptography, blockchain networking, and proof-of-work mining created a true technological novelty. Devotees of Austrian economics flocked to it because it was a money not forced on them by the government, but offered to them in the marketplace. From forum posts, it is clear that Nakamoto was a follower of Austrian theories on gold. Bitcoin’s most cherished feature is its 21 million coin finite supply, which emulates the scarcity of precious metals.

At first, Bitcoin wasn’t sold as a get-rich-quick scheme, but as a political revolution. One of the most famous early Bitcoiners, Roger Ver, earned the nickname Bitcoin Jesus for his evangelistic idealism. As Ver later explained to The New York Times, “At first, almost everyone who got involved did so for philosophical reasons. We saw Bitcoin as a great idea, as a way to separate money from the state.” He and like-minded enthusiasts saw Bitcoin’s finite supply as a solution to central bank money printing that could restore economic order. They extrapolated the market theory of Austrian economics to Bitcoin decentralization. Bitcoin, they claimed, couldn’t be centralized because its openness to all market actors would dissolve any hierarchical structures before they could consolidate. This meant that no central authority could ever change the software to alter the supply, ensuring Bitcoin’s scarcity as a commodity would be maintained.

“Bitcoin decentralization is more myth than reality.”

Seventeen years since its creation, it is clear that Bitcoin decentralization is more myth than reality. This is a direct result of the fact that Bitcoin is not like gold in a crucial respect: You don’t dig it out of the ground. Bitcoin is a byproduct of software, which is written by humans and needs to be updated by humans. Who are these humans? At one point, all of Bitcoin’s software was centralized under Nakamoto’s control. Over time, that control was distributed more widely—but not by much. According to the official Bitcoin website, 346 individuals contributed to Bitcoin’s software. However, just five individuals were responsible for over 50 percent of the code; 20 individuals were responsible for over 75 percent, and 42 individuals for 90 percent. These are the people who maintain and update the code without which Bitcoin wouldn’t exist.

This centralized hierarchy is at odds with the idealized image promoted by Bitcoin supporters, but its existence is acknowledged in internal documents. Bitcoin’s GitHub software repository contains an introductory page titled “Contributing to Bitcoin Core.” Bitcoin Core is the official name of the core group of software developers. The page declares that “hierarchy is necessary” for Bitcoin’s software, and elaborates on the specifics of this hierarchy. The site also previously stated that there was a “lead maintainer” who had all the technical administrative privileges, while other maintainers had similar but subordinate privileges. Together, they formed a centralized committee that gatekept the software from any ad-hoc contributor. While anyone could submit a proposal, only the maintainers could incorporate those into the official software. Thus, Bitcoin’s software was dependent on their decision-making.

The role of lead maintainer passed from Nakamoto to Gavin Andresen in 2011 and then from Andresen to Wladimir van der Laan in 2014. At the 2015 Epicenter Bitcoin conference, Andresen explained his role as “volunteer dictator for Bitcoin Core.” Andresen had close contact with Nakamoto and was deeply involved in the early years of development, so his understanding of the role is significant. In 2023, van der Laan seemed to concede the reality of centralization when he terminated his role and resigned from formal leadership of the project, declaring in a blog post on his personal website that “I am myself … a centralized bottleneck … we need to start taking decentralization seriously.” The clear implication is that they weren’t before.

Following the money makes Bitcoin’s centralization even harder to deny. After the early experimental years, built mostly on volunteer labor, a formal organization was set up to support the software. The Bitcoin Foundation was created in 2012, with Ver, among others, on the leadership team. Its mission stated that it would be “funding the Bitcoin infrastructure, including a core development team.” Funding came from Bitcoin insiders, whether large investors like Ver or companies like Bitcoinstore, Mt. Gox, Bitinstant, Coinbase, and CoinDesk. It is estimated that the foundation had a few million (in dollar terms) under its control to finance developers and other activities. But amid allegations of mismanagement and ties to individuals accused of corruption, criminality, and incompetence, the Bitcoin Foundation became defunct in 2015.

A new centralized authority arose in the same year when the entrepreneur and former MIT Media Lab director Joi Ito announced the launch of the Digital Currency Initiative under his department within MIT. As its website states, “DCI was formed… in order to provide a stable and sustainable funding for long-term Bitcoin Core developers.” Parallel organizations emerged as well. For-profit entities like Blockstream, Block (formerly Square), Xapo, and BitMEX, as well as non-profit organizations like Chaincode Labs and Brink, also helped fund developers.

Contrary to its promoters’ rhetoric, then, Bitcoin is anything but decentralized: Its functionality is maintained by a small and privileged clique of software developers who are funded by a centralized cadre of institutions. If they wanted to change Bitcoin’s 21 million coin finite supply, they could do it with the click of a keyboard. Try doing that with gold.

Bitcoin has failed to live up to the promise of decentralization in other important ways. In his original white paper, Nakamoto defined Bitcoin as “a purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash.” By his account, Bitcoin would be a network of nodes called “miners”—because they “mine” Bitcoin by processing new transactions on the distributed digital ledger known as the blockchain. When someone wants to transmit funds as Bitcoin, he broadcasts his request to all miners in the Bitcoin network, who compete for these transaction requests as inputs to blocks.

Blocks are containers for transactions. Only one block is issued every ten minutes. Each block provides a fixed compensation to miners (called a block reward) and variable fee determined by supply and demand. Blocks are won by miners allocating large quantities of computing power (called hashpower or hashrate) to solving an arbitrary math calculation. Whichever miner solves it first gets the block to process transaction requests and receives the block reward in addition to the variable fees. This new completed block is broadcast to all other miners, who then accept it as part of Bitcoin’s historical accounting record. This consensus of all miners, on that new block’s legitimacy, ensures the operational efficacy of Bitcoin. Once in consensus, all future blocks will be sequentially added to the last block by the same method.

Bitcoin presents itself as a payment processor without middlemen. But don’t miners, who mediate between the digital money and those who want to use it, perform this function? Nakamoto sought to evade the categorization of miners as middlemen by appealing to free-market assumptions. The first was that miners would include all transaction requests—in other words, that they wouldn’t refuse service to and thereby “censor” some users, as a bank or other institution might—because including all requests maximizes their revenue. The second was that miner centralization was improbable because the network was permissionless and open to any entrant. Additionally, Nakamoto claimed, Bitcoin’s structure would incentivize competition and honest processing, which counteracts centralization. For example, it would be counter to the long-term interest of miners to commit fraud because it would diminish the value of their Bitcoin holdings.

In hindsight, these assumptions don’t hold up to scrutiny. Miners can and do censor Bitcoin transactions. As the Princeton computer scientists Malte Möser and Arvind Narayanan have shown, because Bitcoin addresses are akin to bank accounts inside the Bitcoin system, miners can create blacklists of addresses to exclude from each new block. This possibility did not go unnoticed by early Bitcoiners, who debated and warned about the possibility that miners might refuse to process transactions under pressure from regulators.

Real-world examples of censorship would soon pop up. In March of 2018, the Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) in the US Department of the Treasury announced it was considering digital currency address blacklists. In November of 2020, US-based Blockseer Mining Pool launched with the overt aim of censoring transactions from blacklisted addresses using the OFAC guidelines among others. In May 2021, US-based Marathon Digital Holdings’ mining pool created its first “sanctions-compliant” block of Bitcoin using the same OFAC standards. As CEO Fred Thiel noted, the blacklisting was necessary to be compliant with US government oversight. His message was simple: For US-based Bitcoin mining to be increased, US-based Bitcoin miners had to censor.

In short, Nakamoto’s claim that Bitcoin was immune to censorship has been disproven. Miners always had the ability to censor, and there have been documented examples of miners doing just that. When they don’t, that has less to do with the incentives and affordances of the technology than variable conditions and subjective whims.

The broader assumption that Bitcoin’s peer-to-peer market structure works against centralization also collapses under closer examination. Pools—collaborative groups of miners combining computing power—have largely replaced individual miners and mining companies, which means that pool operators act in turn as the principal agents within the peer-to-peer system. By one estimate from Hashrate Index, Foundry USA and Singapore-based AntPool control more than 50 percent of computing power, and the top ten mining pools control over 90 percent. Bitcoin blogger 0xB10C, who analyzed mining data as of April 15, 2025, found that centralization has gone even further than this, “with only six pools mining more than 95 percent of the blocks.”

Even as he promoted the gospel of decentralization, Nakamoto anticipated this outcome. In a November 2008 Cryptography Mailing List email, he wrote: “As the network grows beyond a certain point, it would be left more and more to specialists with server farms of specialized hardware.” On April 12, 2009, in a private email to early Bitcoin software developer Mike Hearn, Nakamoto wrote, “eventually, most nodes may be run by specialists with multiple GPU cards.” In a 2010 forum post, Nakamoto wrote, those nodes “will be big server farms.”

“Bitcoin mining is more costly than ever for new entrants.”

Nonetheless, Nakamoto put his faith in the incentive structures around computing power to mitigate centralization’s corrupting effects. Computing power costs created high stakes, meaning miners had a strong material incentive not to debase the value of the network. Free entry created abundant competition between miners. Nakamoto believed that this combination guarded against the byproducts of centralization even if he couldn’t prevent centralization itself. But today, Bitcoin mining is more costly than ever for new entrants. The only way to have a decent probability of winning a block is to join a pool. Once he has joined, the new miner becomes an appendage of the pool operator. Only those who can raise large sums of capital to create industrial-scale Bitcoin mining farms can effectively compete. Upstart miners, in other words, have turned out to be far less autonomous and less powerful than Nakamoto thought.

Several more blows to Nakamoto’s original vision came during the Bitcoin “Scaling War” between 2014 and 2019, which disproved his hypothesis that computing-power incentives would ensure the integrity of Bitcoin. This conflict was over whether to increase transaction capacity in each block by increasing the block size limit from 1 MB to 2 MB. The impetus for the proposed increase came from miners; in opposition was the “small block” faction, led by Bitcoin software developers. A larger block size would benefit miners by allowing them to include a higher quantity of transactions per block. As Bitcoin adoption increased, so too would demand for sending transactions per block. A higher supply of block space would enable miners to charge affordable fees on individuals while still collecting higher aggregate revenues. If the block size was frozen, on the other hand, fees would necessarily have to increase. This is economics 101: If demand increases without increased supply, then prices must increase.

When Nakamoto and other early developers originally set the block size limit, it was a temporary solution to avoid spam transactions. According to Mike Hearn, Nakamoto “added a quick hack” to manage data transfer and storage problems. But he added that the limit could later be increased. The limit was never meant to be permanent or intrinsic to Bitcoin’s functionality. A car jack is temporarily used to change a tire, but no one would consider the car jack a permanent nor intrinsic feature to a car’s functionality. Neither should anyone assume that with the temporary block size limit. In 2010, Nakamoto explained how it would be possible to scale Bitcoin with larger block sizes. To Nakamoto, then, increasing the block size wasn’t controversial. It was part of his vision.

Contrary to the founder’s intention, core Bitcoin developers argued that Bitcoin was best scaled by way of non-Bitcoin based “layer 2s,” which interfaced with Bitcoin but were not bound by its structure and incentives. Increased Bitcoin transaction capacity would increase the aggregate variable fees miners could receive, whereas frozen Bitcoin transaction capacity meant that providers of layer 2s could divert those fees to themselves. For example, Blockstream—one of the major Bitcoin companies—offered a layer 2 product called the Liquid Network, which promised to accommodate increased demand for transactions. Blockstream employed high-profile Bitcoin Core developers. Digital Garage, co-founded by MIT’s Joi Ito, invested in Blockstream. This put lead maintainer van der Laan, whose role was funded by Ito’s DCI, in the nexus of Blockstream as well. Those advocating an increase in block size considered these connections a conflict of interest and a break with the original intention of Bitcoin.

In his white paper, Nakamoto had stipulated that Bitcoin community decisions, from basic transaction processing to the more complex software upgrades, would be determined by miners. In March of 2017, an upgrade to increase the block size limit to 2 MB was announced. The intention was for the community to debate over the ensuing months and signal their preference. As of May 25, 2017, 83 percent of miners, calculated by computing power, signaled their preference to increase the block size limit. Many Bitcoin-based businesses supported the miners and the upgrade in what became known as the New York Agreement. Miner support for a block size upgrade climbed to over 90 percent by October of the same year.

Nonetheless, a vocal minority of small blockers maintained their opposition. They portrayed miners as powerful oligarchs corrupting Bitcoin for their own benefit. The small blocker’s sought to set aside Nakamoto’s “one-CPU-one-vote” rule, which limited Bitcoin “democracy” to miners. They argued for expanding the definition of Bitcoin nodes to non-mining nodes, which don’t contribute any meaningful computing power to process transactions. This was in effect the “one-IP-address-one-vote” rule that, Nakamoto had warned, “could be subverted by anyone able to allocate many IPs.”

Miners bore substantial costs, which Nakamoto had argued worked as an incentive to increase the value of the network, whereas non-mining nodes had trivial ones. It costs nearly 16,000 times more to run mining nodes than non-mining nodes. The drastically lower cost increases the risk that a minority of special interests could fabricate an illusion of a larger vote. This was also aided by the anonymous nature of Bitcoin actors, which enables the few to hide behind the appearance of the many.

The small blockers appealed to populist rhetoric, pitting the mass of Bitcoin users against allegedly corrupt, oligarchic miners. But in reality, the small blockers were unable to prove a measurable majority, even on their own terms. Nonetheless, the rhetoric had staying power. Social media platforms and informational websites controlled by small block administrators—forums like BitcoinTalk and r/Bitcoin as well as websites like The Bitcoin Wiki and Bitcoin.org—generally promoted the small block side of the debate and censored the big block side. Big blockers started losing confidence in the face of this opposition. As a contingency plan, some big blockers prepared to “fork” Bitcoin, effectively breaking away from the small blockers. On Aug. 1, 2017, some of them forked the Bitcoin blockchain and software into one that had an 8 MB block size. They called it Bitcoin Cash. There were now two Bitcoins.

As more debate ensued, three camps emerged: the Bitcoin (S1X-BTC) that intended to keep the original 1 MB block size on Bitcoin (BTC); the Bitcoin (S2X-BTC) that intended to upgrade to a 2 MB block size on Bitcoin (BTC); and the contingency Bitcoin that had already forked into Bitcoin Cash (BCH) with an 8 MB block size. Whichever camp could claim the brand of Bitcoin and its ticker symbol would gain a substantial advantage. Despite the vast majority of miners preferring option two, the small block faction held firm. On Sept. 11, 2017, Blockstream co-founder and Bitcoin Core developer Matt Corallo wrote a letter to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) urging the government entity to intervene in the Bitcoin market to limit the growth of Bitcoin (S2X-BTC) and Bitcoin Cash (BCH). Incidents like this started to scare the Bitcoin community. For example, support for the big blockers decreased from above 90 percent to about 85 percent, indicating a shift in momentum.

Although almost all miners had signaled their support for the big block side, with much of the businesses and user community in agreement, a concentrated small group of special interests, who never documented any definitive measurement of majority support, coordinated an online campaign to distort perceptions and exert pressure.

This eventually led Bitcoin (S2X-BTC) to voluntarily surrender in early November of 2017. This left only Bitcoin Cash (BCH) as the big block rival to the small block Bitcoin (BTC). According to BitInfoCharts, a big block revolution began rumbling on Nov. 10, 2017 when Bitcoin Cash’s (BCH) computing power doubled overnight and the small block Bitcoin’s (BTC) computing power started to fall. This was a signal that miners were starting to vote in favor of Bitcoin Cash (BCH). On Nov. 11, 2017, Nakamoto’s direct heir and big blocker Gavin Andresen tweeted, “Bitcoin Cash is what I started working on in 2010: a store of value AND means of exchange.” This was like rocket fuel.

Two days later, Bitcoin Cash’s (BCH) computing power overtook the small block Bitcoin’s (BTC) computing power in what became known as the Flippening. The former now composed the majority of total computing power. The small block Bitcoin (BTC) had lost 53 percent of its computing power in only a few days while Bitcoin Cash’s (BCH) computing power had gone up over 6 times in the same period. It appeared that Bitcoin Cash (BCH) was about to win the Scaling War, vindicating Nakamoto’s vision of decentralization. Investors who observed these mining trends started to push Bitcoin Cash’s (BCH) price up and Bitcoin’s (BTC) price down. But somehow it was not enough. The miner Flippening failed to translate to a price Flippening on the cryptocurrency exchanges. This was because, among other things, the small block side had the backing of the crypto industry’s most significant exchange and its money printer.

No cryptocurrency exchange was bigger than Bitfinex. Bitfinex was an early investor in small blocker-led Blockstream. Bitfinex’s executives also managed Tether, the company that pioneered stablecoins: cryptocurrency tokens backed 1-to-1 with the equivalent dollar reserves. Stablecoins are desired for trading because they offer easier use on unregulated cryptocurrency exchanges than traditional dollars. Tether tokens were the blood pumping through the body of the exchange: More tethers equaled more trading.

On Jan. 1, 2017, the tether supply was about $10 million. By Aug. 1, it grew 32 times to a total of $319 million. By Jan. 28, 2018, it was $2.3 billion. In just about one year, the Tether company’s supply of tether tokens and its alleged 1-to-1 reserves grew 230 times. Was Tether such a good product that it attracted that level of customer frenzy? When Tether’s activities were closely examined, it revealed their growth to be more artificial than natural.

University of Texas finance professor John M. Griffin and his doctoral student Amin Shams detailed Tether’s activities in a 2018 paper. For the period of March 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018, Griffin and Shams found plausible evidence to conclude that a few actors printed tethers without real dollar backing to artificially rescue Bitcoin (BTC) when its price fell and stimulate its overall growth. The trading activity was concentrated on Bitfinex with trading patterns not seen on other exchanges. Griffin and Shams also noted the dubious nature of Tether’s reserves and demonstrated unbacked issuance. So long as no one could tell the difference between a tether token and a real dollar, these unbacked tokens could be traded as if they were real dollars. Think of it as a cheat code in a video game for unlimited gold when every other player must grind quests to get them.

According to Griffin and Shams, Bitfinex would receive tethers and use some to buy Bitcoin (BTC) on its own exchange as well as others. If those tethers pushed up Bitcoin’s (BTC) price, Bitfinex’s holdings and Tether’s reserves increased in value. This creates a self-perpetuating flywheel. More tethers fuel higher Bitcoin prices, which increases the US dollar value of reserves (composed partly of Bitcoin) on paper, which fuels more tether printing from the nominal reserve growth. Other researchers like Coinmonks’ Gerard Martínez corroborated Griffin’s and Shams’ paper. But Tether’s unbacked dynamic is best corroborated by legal sources. In April 2019, New York Attorney General Letitia James filed a case against Tether and Bitfinex. Their general counsel’s affidavit admitted that tethers were only 74 percent backed by cash at the time. At a hearing in May of the same year, another attorney for the companies said: “Tether actually did invest in instruments beyond cash and cash equivalents, including Bitcoin, they bought Bitcoin.”

In February 2021, Bitfinex and Tether settled the New York suit for $18.5 million. They were also banned from the state and compelled to submit transparency reports. James’s office stated that “Tether’s claims that its virtual currency was fully backed by US dollars at all times was a lie…starting no later than mid-2017, Tether had no access to banking, anywhere in the world, and so for periods of time held no reserves to back tethers in circulation at the rate of one dollar for every tether, contrary to its representations.” When all these sources are digested together, the logical conclusion is that unbacked dollar-like tokens were printed to tilt prices on an exchange bottleneck. Bitfinex, an exchange with a clear small block conflict of interest, was in total control of what Griffin and Shams described as a pseudo-central bank.

With the victory of the small blockers, Nakamoto’s theory that miners controlled Bitcoin crashed on the shores of reality. Miners were subordinate actors. They were scared of backing the losing side in the Scaling War and having their holdings go to zero. They also had to deal with short-term operating expenses of running server farms, which meant they needed to convert Bitcoin holdings to fiat currencies to pay their bills. The miners couldn’t afford to fight a war of attrition. A decentralized market didn’t decide the outcome of the Scaling War—a small group with conflicts of interest and a de facto money printer did. Bitcoin failed its ultimate test.

“One money printer propped up the whole market.”

The promise of Bitcoin was that decentralization would create an alternative to the unaccountable elite control and corruption of fiat money. As it turned out, software developers held centralized control over the code and could alter it however they chose. As miners matured from hobbyists to industrial-scale server farms, they centralized, which led to the monopolization of the blockchain. In turn, social-media forums and sites dealing with Bitcoin censored speech, and the owners of crypto exchanges were able to pick winners and losers. Finally, these people had the power to print fake dollars in a way that utterly distorted the “market.”

At most five software administrators were in control of 100 percent of the code. Forty-two software developers contributed 90 percent of that code. A few organizations fund those software developers. Six mining pools mined more than 95 percent of the Bitcoin blocks. A handful of exchanges gatekept the buying and selling. One money printer propped up the whole market. The top 1.86 percent of Bitcoin addresses controlled more than 90 percent of Bitcoin’s supply. By comparison, the top 1 percent of America controls just 31 percent of wealth. How is Bitcoin decentralized, again? During the Scaling War, big blockers offered legitimate arguments about the minority status and flaws of the small blockers. What big blockers couldn’t accept is that they were complicit in the same centralizing tendencies as the small blockers they criticized.

Despite its pretense of total autonomy from the state, Bitcoin is dependent on software produced by the government—specifically SHA-256, a cryptographic secure hash algorithm published in 2002 by the US National Security Agency. Without this technology, it couldn’t operate. But Bitcoiners are unable to acknowledge their dependence on the state. By imagining the latter as an entity separate from and opposed to the private sector, Bitcoin believers fail to grasp the reality: As oligarchy grows, it captures the state, and the state’s operating logic gradually becomes that of the oligarchy. Neoliberalism, with its emphasis on free markets, advances this process by weakening democratic checks on the power of oligarchy. Bitcoin is only one example of how free-market ideology obfuscates the true nature of the oligarchy-captured state.

“Bitcoiners are unable to acknowledge their dependence on the state.”

The economist Yanis Varoufakis has described the emerging new variant of neoliberalism “techlordism,” writing that it has supplanted classical liberalism’s belief in the infallible market with a faith in the algorithm as a “new divinity.” Bitcoiners often invoke the sanctity of code, which they present as a quasi-divine being. Tyler Winklevoss, co-founder of the cryptocurrency exchange Gemini, put it this way: “We have elected to put our money and faith in a mathematical framework that is free of politics and human error.” More recently, Brandon Lutnick, chairman of Cantor Fitzgerald (and son of Donald Trump’s commerce secretary), rhapsodized that “the beauty of Bitcoin is the fixed supply … it’s beautiful, it’s scientific, it’s written in code.”

If cryptocurrency enthusiasts are now turning to the state to protect their industry, in line with the broader capture of government by oligarchic interests, those at the highest levels of state power are also trying to instrumentalize cryptocurrencies to their own ends—specifically stablecoins, 99 percent of which are pegged to the US dollar. As Trump has made explicit, he views stablecoins as a way to “extend the dominance of the US dollar to new frontiers.”

The context for this idea is the diminishing role of the US dollar as the world reserve currency. The dollar fell from about 73 percent of global currency reserves in 2000 to about 58 percent in 2022. Trump and his advisers are worried about a global flight from dollar-denominated assets, which will also reduce the federal government’s borrowing capacity and budgetary flexibility. The cryptocurrency trading market, which is reliant on stablecoins denominated in dollars, provides a strategic avenue to reverse the de-dollarization trend. This is because, as Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent tweeted on June 17, a “thriving stablecoin ecosystem will drive demand from the private sector for US Treasuries, which back stablecoins.” This phenomenon is an evolution of what the economist Michael Hudson calls the Treasury Standard. Instead of other countries buying Treasuries with their surplus dollars generated out of the US balance of payments deficit, stablecoin backers would do so. The US government is now pursuing a Stablecoin Standard.

The Trump administration’s embrace of cryptocurrency as a means of shoring up the dollar builds on arguments made within the post-Scaling War Bitcoin world. In February of 2020, crypto investor Nic Carter argued that “far from compromising the dollar’s mighty advantage internationally, cryptocurrency, and the infrastructure built to support it [i.e. stablecoins], may well entrench its position.” Similar arguments were offered by The Bitcoin Policy Institute in 2021. Bitcoin provides a dollar-denominated market for stablecoins. Together, each of their growth supports the US dollar and debt. If one grows, so does the other.

The evolution of crypto narratives also prepared the way for the current administration’s embrace of stablecoins. Although Bitcoin was intended to be a censorship-resistant medium of exchange and store of value independent of governments and central-bank fiat money, the effect of the Scaling War was to split off Bitcoin’s function as a medium of exchange from its function as a store of value. According to the small blockers, Bitcoin would continue to provide a store of value, but “layer 2s” would serve the medium of exchange function, enabling transactions between users. In 2018, economist Saifedean Ammous argued in the book The Bitcoin Standard that Bitcoin, like gold, could be used by governments to back their fiat currencies. Bitcoin could now serve as a tool of the government and central banks as opposed to a weapon of radicals who rejected them.

The dirty secret of the stablecoin strategy is that it directs global dollar flows that would otherwise never pass regulatory scrutiny into the Treasuries market. To whatever degree poor residents of the developing world use stablecoins, as high-minded crypto advocates suggest, to enjoy the stability of a dollar-based financial infrastructure they could never otherwise access, they can only do so because stablecoins don’t provide the same level of regulatory scrutiny that the traditional financial infrastructure does. This ostensibly humanitarian argument, in that sense, is also an admission of massive regulatory evasion. The US government is using this regulatory gap to enable speculative and dark cash flows to flood into the domestic economy and fuel demand for Treasuries, which in turn allows Washington to continue to accrue debt to finance spending even as the rest of the world turns away from its debt and dollar.

As it grows, the stablecoin system is coming to function as a shadow central bank. As of June 2024, stablecoin issuers own $120 billion in US Treasuries, meaning they own more than Germany, the world’s third-largest economy. In 2024, stablecoin issuers were the third biggest purchasers of US Treasury Bills, right behind China. A Bank for International Settlements (BIS) paper published in May of 2025 found that stablecoins not only acted like a central bank, but weakened the existing central bank. Stablecoins depress Treasury yields and have similar effects to “small-scale quantitative easing.”

“As it grows, the stablecoin system is coming to function as a shadow central bank.”

This mirrored monetary power could diminish the effectiveness of the Fed to manage rates. In other words, the Fed pushing and stablecoins pulling cancels each other out. If stablecoins grow even more, their pulling could overpower the Fed. US monetary policy and Treasury rates thus become a function of not just the Federal Reserve nor even market forces, but the centralized discretion of stablecoin issuers like Tether. If stablecoins are unbacked, then the effects on Treasury yields are not only sizable but artificial. Tether has still never undergone a professional audit.

Now that Tether has become a major buyer of US Treasuries and thus a major securer of US strategic interests, there is nothing stopping Tether from doing with the dollar what it did with Bitcoin. Tether would get a limitless fountain of risk-free interest-paying reserves; in return, the government would get a buyer that can always artificially manifest more demand. Both the US government and US private sector gain from Tether evolving from propping up Bitcoin to propping up the government debt and stock market. As long as the flywheel keeps spinning, the US government has a perpetual motion machine to finance any decision its political and business elites choose. Stablecoins, the government, and the corporations all win; a shadow central bank conducts shadow money printing to shadow monetize the debt and shadow quantitative ease.

If this is where we end up, as seems increasingly likely, crypto will be at the heart of the public sector: sovereign debt. It will be tied to the enemy Bitcoin once sought to defeat.

There was no more idealistic Bitcoiner than Ver, the “Bitcoin Jesus” who believed the new currency could bring an end to what he saw as the evil of a financially unconstrained government. Over a decade later, the industry he helped bring into being has become a means of further removing any constraints from debt-financed government spending. A true believer could once make the argument that the ends of Bitcoin justified the dubious means by which it grew—black markets and criminal activity. But today, government debt is increasingly where Bitcoin’s value comes from. Even from a strictly libertarian perspective, then, it is what Shakespeare’s Brutus, in Julius Caesar, calls “money by vile means.”

In 2024, the Department of Justice indicted Ver for tax fraud. He and his supporters contend that this is an unjust persecution. But even under the new pro-crypto Trump administration, Ver is unable to get his case dismissed. For all Ver’s advocacy and idealism, he has been hung out to dry by his own people while Bitcoin and stablecoins fuse more and more with his despised government. Ver used his Bitcoin wealth to fund Anti-war.com with the catchphrase “Bitcoin Not Bombs;” now, Coinbase sponsors military parades in Washington, DC. Even so, Ver can’t bring himself to admit that Bitcoin’s myth was wrong. He and other Bitcoiners delude themselves into perpetuating a myth that props up the very things they once revolted against.

When Brutus, in Act IV, Scene III of Julius Caesar, declares to Cassius that he “can raise no money by vile means,” he is forced to recognize the gap between his ideals and the sordid reality of the conspiracy in which he has become entangled. In truth, there are no means other than vile ones for him to raise the money, just as there were no means other than vile ones to have carried out their murderous plot against Caesar. Just as Brutus uses noble rhetoric to shroud the vileness of the conspiracy, Bitcoin zealots have claimed, ever since the creation of the first cryptocurrency, to be noble-minded opponents of financial corruption and the tyranny of fiat money. By overthrowing that despotic regime, they have assured us, a just restoration of order and fairness can be achieved. History has revealed that promise to be just as legitimate as Cassius’s.

At the end of Shakespeare’s play, Brutus falls on his own sword, having begun to accept the folly of his ways. Idealistic Bitcoiners should—metaphorically—do the same. However noble their intentions were at the outset, they have given rise to something far worse. Bitcoin and its Frankenstein’s monster of stablecoins are the latest phase of the longer neoliberal trajectory of privatizing public services and responsibilities. As the economist David McWilliams wrote in his 2024 book Money, “the battle over who controls and creates money has been waged for millennia…All these were efforts aimed at privatising public money and the latest example in this illustrious list is crypto…For all its faults, the fiat system is still a [democratic] state-run system…the state giving up [the control of money]...would be to give the private sector control over the most potent substance in the state’s armory.” When I was first inspired by Bitcoin in 2013, it was because it claimed to offer a means for ordinary people to check the powerful and corrupt. Over a decade later, it is clear this was a false promise. The only way to achieve this, on the contrary, is to use the democratic process to make money “for the people and by the people.”

In 1776, American colonists rose up against the English to demand representation in government. As feudal aristocrats gave way to financial oligarchs, later American nationalists fought against the rise of oligarchic private banks. The first case for a democratic central banking system, in opposition to 19th century financiers, promoted by Irish-American economist Henry C. Carey and championed by Abraham Lincoln. Bitcoin and stablecoins are the new instantiation of this long-war between democratic and oligarchic control. At the end of Julius Caesar, Mark Antony turned to his “friends, Romans, countrymen” to rally the people against the elites who had conspired against Caesar. In the same spirit, the only way to defeat vile money and limit the power of oligarchs is through the democratic power of an awakened people.