At Thanksgiving, Americans used to give thanks to God, and to ask him to forgive, in the words of George Washington, our “national and other transgressions.” In our time, they have been asked to thank no one in particular, but to gesture with gratitude toward themselves. It expresses therapeutic rather than Christian faith, powered by a gratitude industry that promises the modern equivalent of salvation: mental health.

Pop science underlies this belief. According to Psychology Today a meta-analysis proves “gratitude practices have a positive effect on well-being.” It’s trivially true that if you ask people to sit and think about nice things, they will feel a little nicer. But therapeutic gratitude can’t fill in for a broader loss of meaning. The trouble is that Americans seem no longer so sure to whom or for what gratitude is owed.

That hasn’t always been the case. Early New England Thanksgivings, for all their questionable mythologization, were acts of providential piety. The Puritans believed, in the words of the historian Francis J. Bremer, that “all men deserve damnation.” But “God in his benevolence chose to save some men in spite of their unworthiness.” For them, gratitude was vertical and external. It was part of a moral order that lay outside of human control.

But the harvest feasts and general days of fasting and thanksgiving dotted throughout the year gave way to a more encompassing purpose. By the 19th century, Thanksgiving became a national rite. The fractured republic needed a shared civic festival, and after years of campaigning by the influential editor Sarah Josepha Hale, Abraham Lincoln provided it in his 1863 proclamation declaring the last Thursday in November a national day of “Thanksgiving and Praise.” Fusing the old religious meaning with a new, national one, it declared the Union’s survival a “gracious gift of the Most High God.” Gratitude was put to use for the symbolic repair of the nation, anchored in a providential vision of the Republic. It was still vertical and external, but this time tied more concretely to the shared task of nation-building.

However, by the mid-20th century the impulse behind this task, the sense of belonging to something greater for which one should be grateful, began to wear thin. Thanksgiving had long been a rite of family reunion, and stories of jubilant homecomings had been burned into public consciousness by sentimental magazine stories, often overseen by Hale herself. Like other holidays, Thanksgiving became focused on the family home. The religious and civic elements were still there but felt perfunctory. Gratitude became more domesticated, horizontal, and sentimental.

“Gratitude became one of the tools of the positive psychology boom.”

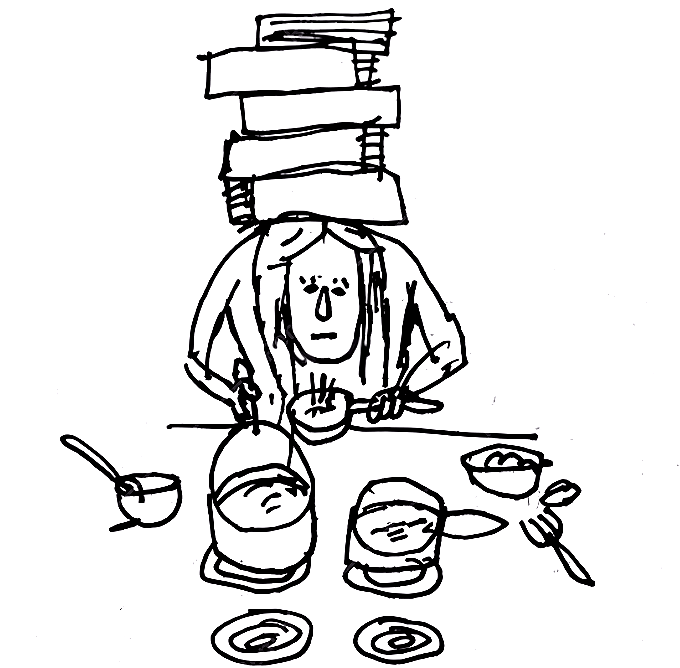

By the turn of the millennium, the invitation to gratitude shifted inward, toward a more internal and personal frame of reference. God, nation, and family lost their centrality. Gratitude became one of the tools of the positive psychology boom. This movement filled in the void left by the decline of aspirations to personal holiness or social progress. Its leaders preached mantras of personal resilience, coping, and “well-being.” Therapeutic gratitude was uncontroversial, apparently secular, and came with a supposed evidence base to back it up. Government proclamations now regard gratitude as a practice that can build “social capital” and improve your “mental well-being.” This gratitude is not directed toward anyone in particular. It is a feeling to be cultivated as part of the good citizen’s mental hygiene.

And yet this year, as I combed through the typical Thanksgiving headlines about how being grateful will increase your well-being score by this or that many points, something felt so much more passé about it all. Fewer people seem willing to accept that coping is really all we are called to do. The positive-psychology script is still being earnestly updated, but emotional regulation as the horizon of politics made much more sense when it seemed PR-savvy vacuous politics was the “end of history.” But things feel different now.

Of course, the void that therapeutic gratitude tried to fill hasn’t gone anywhere. We still do not have a widely shared, “thick” answer to the question of what we, as a society, ought to be thankful for. God, if he exists at all, is largely private; references to the nation feel narrow and partisan; and the family is take-it-or-leave-it (and for the good of your well-being, you should probably leave it).

But the thin therapeutic plaster is starting to crack. It seems not coincidental that at the height of “gratitude” as a bestselling therapeutic object in the mid-2010s, the fashionable thanksgiving posture in liberal circles was: Don’t go. Cut off the Trump-voting relatives and protect your emotional equilibrium. Remove the “triggers,” have a “friendsgiving.”

But the vaguely farcical Trump-Mamdani meeting in the lead-up to this Thanksgiving seemed to signal that something has shifted. New York City’s democratic socialist mayor-elect has spent years calling Trump a fascist and a despot. In the Oval Office, when asked if he still believes that, Mamdani seemed to hesitate. “That’s okay,” Trump laughed. “You can just say yes.” They then spent most of the meeting talking about rent and grocery bills, ending with a promise to work together on affordability.

The mood is murkier, but in an odd way, more grown up. Even over on Bluesky, the prevailing sentiment is less “cut them off” than, “how to roast your MAGA uncle.” In other words, you might feel contempt, but you’ll still be there. You might even have a bust up, but you’ll still pass each other the potatoes.

It is hardly the reconciliation of 1863, but it does at least concede that political disagreement isn’t a mental health crisis. Therapeutic gratitude tried to turn all the mess into a coping strategy. But being an adult means recognizing that life feels bad a good deal of the time, people can be infuriating, and disagreement can be annoying and sometimes productive. Gratitude became a therapeutic ritual, but it is best when it carries a faint recognition that, despite everything, we still have each other and a whole world to wrestle with.