The UK Supreme Court’s recent ruling that “woman” and “man” in the Equality Act refer to biological sex has been hailed as a landmark victory for gender-critical views. However, it might prove far more difficult to walk gender madness back, not just in Britain, but around the world. This is because for decades, our governing institutions have been dead set on transing the political subject. Great Britain might be reawakening to the reality of biological sex, but a worldwide effort to push society toward a collective sex change is still underway.

For example, across sub-Saharan Africa, UNESCO’s “Our Rights, Our Lives, Our Future” (O3) program, funded by European governments and the Packard Foundation, promotes comprehensive sex education in 35 countries including some of the poorest in the world. One of its key aims is to “challenge gender norms, specifically targeting children aged 5–12.” Curricula encourage children to reflect on their internal “gender identity” and to see gender norms—paradoxically—as both harmful and as a deeply held sense of self that must be respected. Programs like this reposition gender recognition as a human right on par with access to food, water, and shelter.

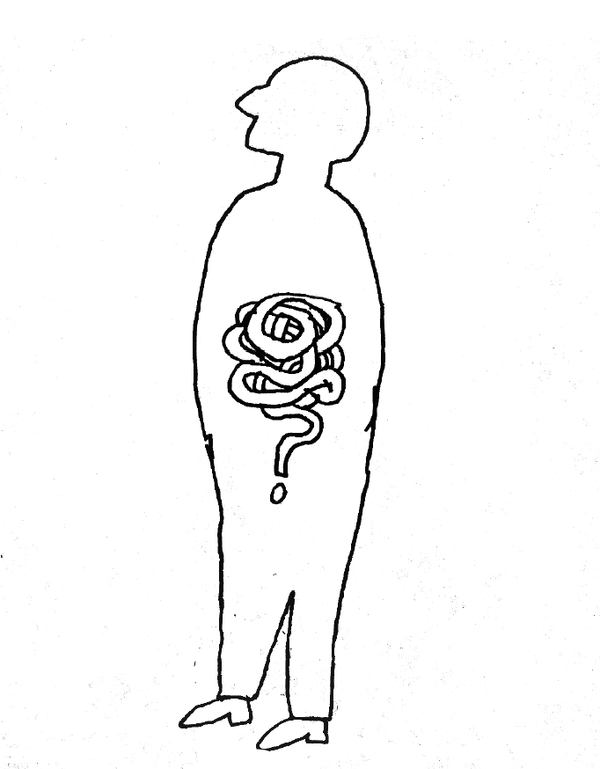

The only way to make sense of the commitment to this agenda is to realize that “gender identity at variance with biological sex” has become a master signifier for suspicion of the old ideal political subject of liberal democracy. This was the vision of the rational citizen capable of reasoned reflection. This capacity made him the cornerstone of liberal society—it was why he could sign contracts, vote, and consent to be governed.

But in recent decades, this “he”—this implied masculine universal—came to be seen as a hindrance to social progress. As feminist theorist Monique Wittig observed, “The universal has been, and is continually, at every moment, appropriated by men.” Judith Butler used such critiques as a launchpad for dismantling the very idea of a coherent subject at all, writing: “the question of women as the subject of feminism raises the possibility that there may not be a subject who stands ‘before’ the law, awaiting representation in or by the law.”

But the ideal liberal subject did not wither away in the face of such critiques—he simply transitioned. Butler’s statement can be taken prescriptively: If the subject is constructed, then it can also be reconstructed into something more governable, adaptable, and “resilient.”

A similar logic is at work when left-leaning economists like Joseph Stiglitz tell us that the rational, calculating homo economicus is a myth. “Individuals act systematically in an irrational manner,” Stiglitz says in his post-2008 crash analysis, echoing the now standard claims of behavioral economists who present themselves as critics of economic orthodoxy.

This sounds progressive—after all, wasn’t the myth of homo economicus a tool of capitalist ideology? But this supposed critique actually lends support to our ruling misanthropology. As Philip Mirowski argues, when reality fails to conform to economic models, economists don’t revise their theories—they blame human nature. Subjects are no longer the bearers of reason but the source of risk, persistently failing to behave as they “should.” And so rationality must be kept at a safe distance from irrational man: in evidence-based policy, predictive models, and trained “expert consensus.” The more impersonal and opaque, the more “scientific,” the more we free ourselves from fundamental human frailty.

“Problematic” men today still stubbornly cling to the myth of rationality. They believe in their own judgment; they selfishly demand more in the workplace. The working-class movements of the 19th century were a profoundly destabilizing force, and they were movements of “working men.” Masculinity comes to represent all that elite governance fears: populism, resistance, the refusal to comply. Once the bearer of liberal democracy, the old ideal of the citizen becomes the saboteur of our new “democracy” of managed compliance.

“Transition signifies letting go of these old attachments.”

Tradition and culture, from this perspective, are distorting forces that lead to poor choices and an inability to adapt. Transition signifies letting go of these old attachments. In this regard, transgenderism epitomizes a model of subjectivity prized by technocratic elites: malleable, untethered from tradition, and committed to an endless project of self-creation. Gender-identity literature emphasizes that “coming out” is not a one-time act but a lifelong process across ever-changing jobs, homes, and relationships, implying an ideal subject ever ready to adapt themselves to an ever-changing world. A fluid subject for a fluid world.

This is the ideal political subject for today’s postliberal managerialism: heteronomous and willing to doubt its own judgment and intuition. People need not transition to live up to its ideals. By accepting the assertion that I cannot know the gender of the person sitting in front of me, I am accepting that I must doubt the evidence of my own eyes and look to others for an official line on reality. Nor can tradition or common sense tell me how to understand and treat others: I must look now to new official guidelines for the correct language and rituals. And since these are always changing, I must be ever alert, ever malleable, ever willing to shift to new truths.

The embrace of gender identity, then, isn’t a cultural detour but the very logic of contemporary technocratic rule: distrustful of ordinary people, hostile to autonomy, obsessed with management. UNESCO’s work in Africa shows how global this project has become. When schools without plumbing receive gender-identity curricula, it becomes clear this is not about local need. It is about making new kinds of people suited to a new kind of world-building, which no longer happens in bricks and steel but inside people’s heads.