Americans, it is often observed, have lost their capacity to laugh. The culprit for the widely lamented “death of comedy” seems clear enough. The intense political division in American society has sent partisans to the barricades. On one side stand the battalions of the perpetually offended, eager to ferret out victimization, defend the marginalized, and cancel the perpetrators. On the other side rally defenders of tradition, furious at what they see as unrelenting attacks on mainstream values by the legacy news media and the education and entertainment establishments. Many others have been caught in the crossfire.

One of the fatal casualties of this raging culture war, it seems, has been our ability to find things funny. Like everything else, humor has been relentlessly politicized and thereby narrowed to the point of oblivion. Laughing about public issues, ideological disputes, or controversial figures has become increasingly dangerous and divisive as even the most innocuous jokes are subjected to hostile partisan readings. Surges of anger, outbursts of moral preening, and the cultivation of delicate feelings among great swaths of Americans have made it nearly impossible to make light of anything or anyone in modern life without offending someone. Comics including Jerry Seinfeld, Mel Brooks, Dave Chappell, and Shane Gillis have complained about the swelling sensitivity that has hamstrung humor and led to firings and cancellations.

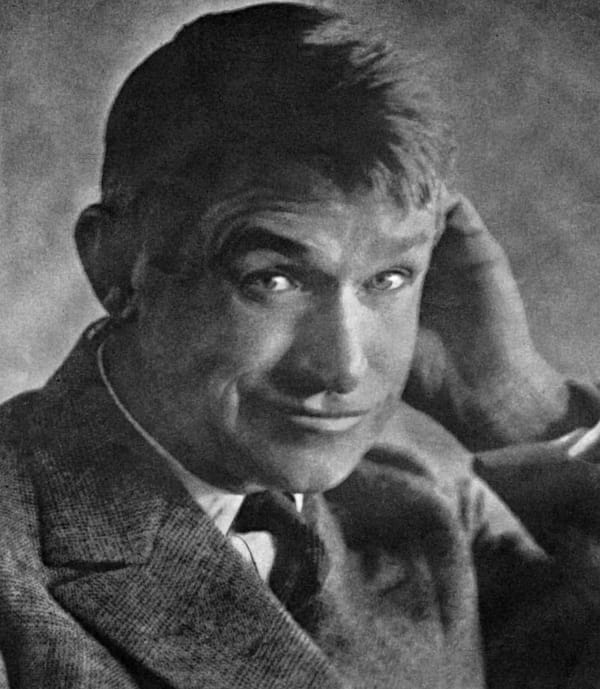

“He became the nation’s most popular comic commentator.”

The humor that does break the surface is often mean-spirited and mocking—you only laugh by denigrating and insulting your political opponents. This is especially true with late-night comedy shows, once a mainstay of American entertainment. Over the last decade Jimmy Kimmel, Jimmy Fallon, Seth Meyers, and Stephen Colbert have relied on relentless mockery of Donald Trump and Republicans for much of their comic commentary, while giving a free pass to liberals. The controversy surrounding CBS’s recent cancelling of Colbert’s show—arguably the result of his unrelenting, tedious leftist tirades causing popularity and economic losses—illustrates the broader decline of late-night comedy. As Jay Leno, the former host of The Tonight Show, recently warned, “I love political humor, don’t get me wrong. But [backlash] happens when [hosts] wind up cozying too much to one side or the other . . . . I don’t think anybody wants to hear a lecture. Why shoot for just half an audience? Why not try to get the whole?”

Is there any hope for finding a way to chuckle at the silly, sordid events of our day and the flawed human beings who struggle to deal with them? Will it ever again be possible to make jokes on public affairs topics that go beyond a partisan appeal and reach a wide audience?

Perhaps, and an example from a century ago shows how. For two decades from the late 1910s to the mid-1930s, Will Rogers tickled America’s funny bone with his commentary in a variety of venues—on stage, in writing, on radio, and on the silver screen. He did so not by avoiding political and social controversies, but by tackling them head-on in a spirit of good will, generosity, even-handedness, and fairness, eschewing cheap point-making for wit, cleverness, and shrewd insight. Prompting much laughter and inspiring little rancor, he became the nation’s most popular comic commentator. His example deserves our attention.