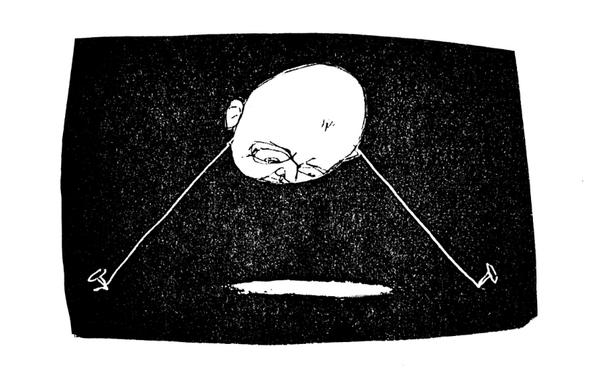

A Prisoner’s Cinema

By Justin Lee

Passage Press, 264 pages, $29.95

As I made my way past the window displays and Salvation Army Santas on Fifth Avenue, I happened upon a sign that read “This Holiday Season, Give the Gift of Kindness!” Who wants to wake up to find “kindness” sitting under their tree, I wondered. Of course, the world could always use a little more kindness and good manners. But there was little that could be called respectable or “nice” about Christ’s life on earth. Between being born in abject conditions in a stable and dying a gruesome death, he spent his lifetime clashing with the religious authorities of his day and hanging around prostitutes, lepers, and other social rejects.

“Some stories left me feeling revolted to the point of sickness.”

I bore this in mind as I read Justin Lee’s A Prisoner’s Cinema. The collection of short stories published by Passage Press, which was founded in 2022 to “as an alternative to the increasingly closed-minded worldview of modern mainstream publishing,” dabbles in horror, the grotesque, and at times the downright disgusting. Some stories left me feeling revolted to the point of sickness. Yet what makes Lee’s debut collection notable is not its grotesqueries, but the fact that filth does not have the last word.

Throughout the twelve short stories, we encounter an array of characters who are faced with horrors as mundane as sexual repression and as fantastical as a shape-shifting demon. The collection opens at a show featuring a Bosniak mesmerist who is determined to “make believers” out of the skeptics in the audience. His tricks range from erasing an arachnophobe’s fear of spiders by placing one in his hand to calling up another audience member’s repressed memory of watching his mother get killed by Serbian soldiers in the 1990s.

Memories are a source of grace as well as horror. In “Lightning in a Cloudless Sky,” Michael reluctantly attempts to protect his drug-addicted brother, Dane, who’s on the run from Black Rob, an imposing “wigger” to whom Dane owes $1000. After a series of verbal and physical altercations with his brother, Michael happens upon old VHS tapes of the two of them as kids. Dane refuses to watch them at first, but his rigid exterior eventually melts away. His confrontation with his lost innocence brings him to tears. Just before Black Rob begins pounding on the door to demand his money, Dane disappears and is replaced by his eight-year-old self, who miraculously emerges from the screen. Michael fights and chases away a confused Black Rob as little Dane watches from the other room. We’re left with a tender scene of the two brothers on a boat, as if they’re sailing away from the demons that poisoned their affection for each other.

Much of Lee’s collection evokes the “God-haunted” world of Flannery O’Connor, where doubt-filled characters are plagued, and at times consoled, by the sense that God—despite his silence in the face of human suffering—is indeed present. In “Lovecraft,” Colin admits to having “drifted in the aimless ambiguity of a faithless adulthood” after being “decidedly religious” in his youth. Ever since his girlfriend Meredith was brutally raped, the cruelty of the world leaves him unable feel any kind of religious wonder. Nonetheless, Colin retains the sense that God is hidden somewhere within life’s absurdity—perhaps as a monster “residing beneath me in the depths of the ocean.”

In “Faintly Falling.” Michael, a bookish evangelical Christian, finds himself plagued by his sexual desires and spiritual emptiness. While reading Saint John of the Cross’s sixteenth-century The Dark Night of the Soul, he cries out to the heavens asking: “Where are you? Why is this so difficult? Why so fucking difficult?” Soon after, he dreams of walking into a hospital room to find Jesus dying with IVs poking his veins and an oxygen mask over his face.

While continuing to read the Carmelite mystic’s love poetry directed to God, Michael is forced to confront the sexual shame imparted to him by his puritanical upbringing. “According to St. John, sexual temptation of a ferocious nature will certainly arise and in all likelihood coincide with the peak of the night, with the darkest, lowest hour. In order to pass through the night this temptation must be mastered.” Is sexual desire a curse or a gift? Are suffering and temptation things to be swept under the rug, or to be endured in order to reach the heights of spiritual ecstasy?

Perhaps the most disturbing story of the collection demands how far God’s mercy is able to reach into the depths of evil. Cal, who is on death row for raping children, is tormented by a demon named Paul who is determined to convince him that he’s bound straight for hell, and that no amount of repentance can redeem him. Lee boldly juxtaposes gruesome descriptions of Cal’s vile sins with moments of “tender mercy” and unsuspecting grace.

At Christmas, Christians celebrate the scandalous fact that God took on mortality in order to be executed as a criminal. Not all Christians will be prepared to celebrate Lee’s book, which certainly has its grotesque and graphic passages. But Christ is not foreign to the horrors and absurdities that plague humanity. In taking on human form, he took on humanity’s sins as well, bearing their weight so we might live. A God who doesn’t descend to the depths of hell cannot offer real redemption. He can only mask it, while it threatens to crack through the surface of our false propriety.