Lillian, a senior at the University of Virginia, is taking a step that has scandalized her parents, peers, and professors. It has nothing to do with her performance at UVA. Lillian is killing it academically. She is a dedicated volunteer in Charlottesville, and looks primed to make her mark on the world. In these ways, she is a typical student at Mr. Jefferson’s university. But what makes her really stand out from the crowd at UVA is that she is planning on getting married this year, in November, at the age of twenty-two.

Her early marriage plans did not go over well with her parents, at least not initially. When Lillian told her parents, they “weren’t immediately supportive”—in fact, they were “angry, maybe heartbroken.” She added, “They want what’s best for me, and they defined that as seeing the world, working for [awhile], and ‘realizing my full potential’ before settling down. While I understand the appeal of that [conventional] path—and sure, a random weekend trip to Spain sounds nice—it simply doesn’t measure up to the importance of marriage for me.”

Her parents’ concerns about her marrying young were echoed by many of her professors, friends, and other family members. “Marrying young is [viewed as] abnormal” for many of her college friends and mentors, she said. They think your twenties are for “figuring out who you are,” having fun, and—above all—getting your career launched. One professor at UVA put it this way: “You’re throwing your whole life away. Why would I help you get a job if you’re not going to work that long? You could be something really cool on Wall Street, and you’re choosing marriage instead.”

The pushback has been profound because so many of her peers and professors are devoted to what I’ve called the “Midas Mindset”—the idea that what matters most in your life is building your own individual brand, seeing work as the summit of your life, and steering clear of the encumbrances of family life in your twenties. Your twenties are supposed to be devoted to education, work, and fun. This decade is for self-development and having the freedom and independence to do what you want, when you want. Only after you have gotten all your ducks in a row, around the age of thirty, are you supposed to even think about something or someone beyond yourself—to lean into love, marriage, and family life.

“I’ve had to fight off [so much] unsolicited ‘advice’ and cling to what I know to be true: I am ready to be married,” she told me. Her relationship is strong, she and her boyfriend are mature, she is eager to start a family, and she is devoted to her Christian faith. What matters most to her (besides her faith) is marriage and family and she’s ready to get started on both. “Why should I delay the life I truly want and know is right just because society calls it ‘abnormal’?”

Although Lillian is in the minority at UVA, her pursuit of early marriage is supported by a growing chorus of voices on the right. From online influencers such as Riley Gaines to White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt, from conservative pundits like Ben Shapiro to tech billionaires like Palmer Luckey, young marriage is getting renewed attention as a valuable option. But no one has given voice to the case for young marriage more prominently and insistently on the right than Charlie Kirk, who was killed five months ago.

To be honest, I had not paid a lot of attention to Kirk prior to his assassination on September 10, beyond knowing that he was a prominent Republican political organizer and campus activist. But after he was killed, I learned that besides being a big player in politics, Kirk had also been a powerful and prophetic voice on behalf of something bigger than politics: the American family. I also came to learn that this man, a man who never even graduated from college, was possessed of more wisdom than many academics when it came to our most fundamental social institution, marriage. Not only did he frequently and eloquently articulate the value of marriage and family in general, but he also made the case for young marriage in particular. In fact, Lillian named Kirk as one of the thinkers who shaped her decision to embrace young marriage.

Kirk’s case for twenty-something marriage to young adults was three-fold. First, the culture is telling you to lean into work and travel. But working for the man and “traveling to Thailand” is not going to bring you the fulfillment you think it will. Second, you will minimize your odds of being miserable and maximize your odds of living a meaningful and happy life by getting married and having kids. So, don’t wait to embark on life’s most important journey. Third, do not assume that you can wait until your thirties to find a spouse and start your family. If you wait, you may miss out.

“If you wait, you may miss out.”

Of course, as Lillian’s experience indicates, Kirk’s view is by no means the majority view today. Most professors, peers, and parents encourage young adults to steer clear of a trip down the altar and focus instead on money and work. A recent Pew survey found that nearly nine in ten parents say financial independence and career fulfillment are crucial for their kids. But when it comes to marriage and children? Only one in five think those are extremely or very “important” for their kids when they reach adulthood. As Kay Hymowitz observed, “college-educated professionals and devoted parents [prod] their kids to prepare for the Big Career. When it [comes] to that other crucial life goal—finding a loyal, loving spouse, a devoted parent for their grandchildren—their lips [are] sealed.”

This helps explain why students such as Holly, a recent UVA graduate, told me that “UVA students are definitely more focused on their education and getting their career started than getting into a serious relationship,” adding: “If it happens, great, but the focus is definitely on building our own brands first. The thought process is, relationships and love are a risk, but you will always have your career and success to fall back on— at least while you are young.” She’s not alone. Young adults overwhelmingly prioritize the Midas Mindset over marriage: while 75 percent of eighteen- to forty-year-olds consider making a good living crucial to fulfillment and 64 percent say the same about education, according to one recent poll, just 32 percent view marriage as essential.

But the path to living a meaningful and fulfilling life, as Kirk realized, is much more likely to run through marriage and family than it is through money and work, not to mention traveling to Thailand. Of course, there are plenty of voices in mainstream and social media today telling young women and men otherwise. From the left, we have writers like Amy Shearn in The New York Times insisting that “married heterosexual motherhood in America … is a game no one wins.” From the right, online influencers like Andrew Tate assure us that “the problem is, there is zero advantage to marriage in the Western world for a man.”

Elizabeth, a thirty-four-year-old lawyer living in Texas, would beg to differ with these marriage and family naysayers. She’s living the dream valorized by the Midas Mindset—she has graduated from a top college in the South, gotten a fancy law degree, works for Big Law, and pulls down a large six-figure salary. But financial and professional success have not been enough. She is feeling alone and dissatisfied with a life that hasn’t yet led to marriage and motherhood.

A recent visit to her sister’s home crystalized her sense of dissatisfaction. “My sister just had her third baby,” she told me, also noting that her sister and her husband are struggling financially to stay afloat supporting their growing family. Meanwhile, on the very day she was visiting them, Elizabeth got news from her boss that she had received a promotion and salary boost at the Texas law firm where she works.

But visiting with her sister and newest niece at their home that day, Elizabeth didn’t feel happy about her promotion; she just felt sad about the absence of family in her life. “I sat there on the stairs in the house with her [and the baby],” she said, continuing, “And I would have given every dollar in my bank account to have my sister’s life… How empty the promotion felt when my sister has her third baby.”

Charlie Kirk would not be surprised by Elizabeth’s dissatisfaction. He knew young adults’ faith in the Midas Mindset was mistaken. In a podcast the day before he was killed, Kirk said that young women without families were more likely to be “miserable.”

Kirk’s way of framing the issue is off-putting to many. But he is onto something. Young women (aged 22-35) who are single like Elizabeth are indeed more likely to report that they are lonely and unsatisfied with their lives. Fifty-five percent report that they are frequently lonely compared to 36 percent who are married; likewise, 47 percent of unmarried young women say they are “not satisfied” with their lives, compared to just 18 percent who are married, according to the American Family Survey.

It’s not just women. Young men (22-35) who are single and childless are also more likely to be lonely and unsatisfied with their lives. Unmarried young men are 23 percentage points more likely to be frequently lonely and more than twice as likely to be unsatisfied with their lives compared to their married peers. One thirty-something man pulling in a healthy six-figure salary in New York City underlined his frustrations with his love life in this way: “Even for those of us who are successful in other areas of life, the [way] these dating apps [rate us] feels futile and transactional,” adding he had not been able to find a good relationship. “The experience is immensely lonely.”

The inverse is also true. Kirk was a big booster of twenty-something marriage in part because he saw it as the best path to forging a meaningful and happy life for young adults. He noted the “happiest women in America are married with children” and encouraged his followers to “Live life to the full” by forming families.

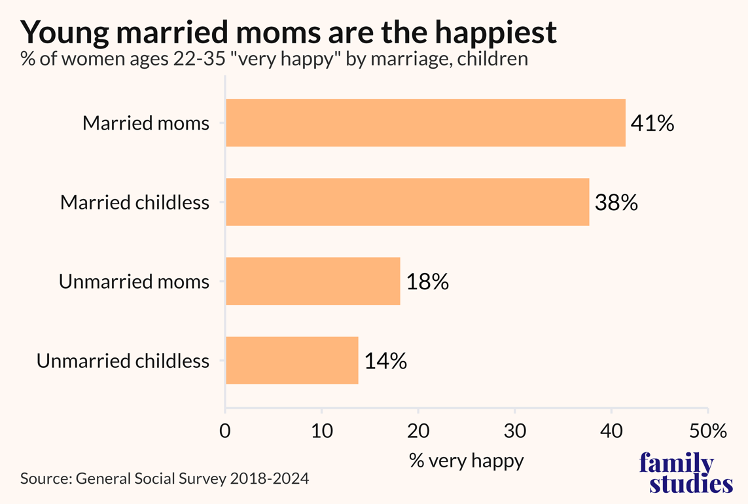

Here again, Kirk knew what he was talking about. You might not guess it from watching the latest episode of Emily in Paris, but the happiest young women (22-35) today are not footloose and fancy free, they are married moms. And the ones least likely to be happy are single and childless. Data from the General Social Survey indicate that 41 percent of young married moms (22-35) are “very happy” with their lives, compared to just 14 percent of their female peers who are single and childless. That’s a big gap.

What is particularly striking about this gap is that it flies in the face of conventional wisdom among single women today. A majority (55 percent) of unmarried women today believe that single women are typically happier than married women, according to a recent poll from the Survey Center on American Life. Conditioned by social and mainstream media to view marriage and family as constraints on women’s freedom, exposed to one pop cultural offering after another depicting urban single life as the best, and occasionally frustrated by lackluster dating experiences, many young women have grown skeptical of our oldest social institution.

But these marriage skeptics haven’t met Samantha. This young woman met her future husband in New York City in her early twenties, while working in the theater. At that point, she was “eat, sleep, and breathe Broadway” and living in a world where most of her friends put “career first, family second.” But after meeting and falling in love with Joey, who shared her Catholic faith and love of family, she decided to forge a different path. Samantha got married, left New York for the more family-friendly environs of Texas and started a family.

“I don’t miss that season, because I love the season that I made,” said this twenty-nine-year-old wife and mother of two young children, who now works part time in the theater. “I don’t want to miss a moment with the kids and with Joey, and it brings me even more joy to sit down and be able to have dinner with my husband every night than to be off on a stage every night” without them. Samantha is clearly happy amidst the hubbub of family life.

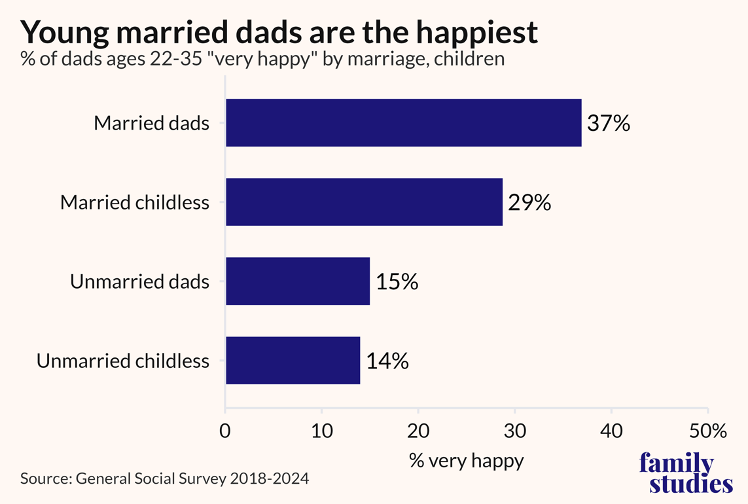

What about young men? Kirk once observed that for men, getting married amounted to a kind of death—“It’s the death of the bachelor mindset. It’s the death of the wondering eye. It’s the death of ‘I get what I want to do.’ It’s the death of playing video games until 1 a.m..” That may seem off-putting to some young men, but Kirk went on to say, of marriage and men, that “it’s the birth of a man” who now finds meaning, direction, purpose in something larger than himself, and is happy for it.

Samantha’s husband, Joey, whom I taught when he was an undergraduate at UVA, would certainly agree with the idea that twenty-something marriage has involved sacrifices, though not quite the ones Kirk mentioned. Once they decided to get married, Joey left his high-flying finance job in New York City for a more “family-oriented” firm in Dallas that would give him more time with Samantha and the kids they hoped to have.

This twenty-nine-year-old finds family life in Texas much more meaningful than his single phase in New York. “When you’re single, there’s a lot of excitement. But it’s all individual, right? Everything is experienced just by yourself,” he said, adding, “The world opens up so much more when you have a life partner, and a family that you can experience it with together.” Getting married and having kids, for Joey, means “experiencing their joy on top of your joy—it is exponential.”

Indeed, young married men (22-35) who are married with children are almost three times as likely to be “very happy” with their lives compared to their peers who are single and childless. Only 14 percent of young men who are single and childless are “very happy” compared to 37 percent of their peers who are married fathers. Not only are young adults who put a ring on it happier with their lives in general, the research also suggests they enjoy marriages that are somewhat happier and more sexually satisfying than those who marry later. These data suggest young men and women who take their cues from pop culture—whether classic shows like Friends or contemporary series like Adults, both celebrating single life in New York City—may be in for a rude surprise. Because the reality is that today’s young men and women who reject this path, like Joey and Samantha, are the ones truly thriving.

Most of the students that I teach at the University of Virginia are planning on waiting until around thirty to marry and start a family. One reason this is their plan is that it is the current social convention—the median age at first marriage is close to thirty for today’s young adults, according to the census. Another is that most of their parents expect them to wait until around thirty to put a ring on it.

Zach’s experience with his parents is typical. Although the twenty-two-year-old senior at UVA is personally hoping to marry his long-term girlfriend in the next two years, his parents had more conventional expectations for him. Their message to him was “you’re very young, definitely don’t tie yourself down,” he told me, adding that from their perspective “obviously college and career are the important things to focus on right now.” Like most parents, they assumed Zach could focus on building a relationship in his late twenties and then get married as he approached thirty.

This was Elizabeth’s view, as well, when she was in college and law school in her early and mid-twenties. She had dated successfully in high school growing up in Texas, describes herself as “reasonably attractive” and “friendly” and simply assumed that it would be easy to date in her twenties, after she had finished law school. Back in her early twenties, she said, “I was thinking more about just, you know, education and work,” adding, “I wanted to get married, but pursuing it wasn’t a priority.” She thought she had time to focus on education and work in her early twenties and then pivot to finding a husband in her late twenties. This approach to sequencing education, work and marriage that “was in the air” when she was in her twenties. Hence, she did not “feel any urgency in pursuing a relationship” in her early twenties.

She now regrets that. Because after graduating from law school in her mid-twenties, she spent almost two years in New York City working long hours at a big law firm until she was twenty-seven. She found the New York dating scene difficult, in part because her job required “insane” hours that did not leave much time for socializing. But when she returned to Texas, she did not find dating—primarily through online platforms—much easier in her late twenties. In fact, online dating was hard, because there is no easy “way of figuring out chemistry” through online profiles. And she was getting nervous in her late twenties, realizing that she would have to find a good guy, establish a relationship, marry, and start having kids before her biological clock might make getting pregnant more difficult.

Her concerns about the timeline for forming a family were legitimate. That’s because even though she did find a serious boyfriend in her early thirties, that relationship recently ended when he made it clear he did not want children. So, right now, at the age of thirty-four, Elizabeth has no clear path towards marriage and motherhood.

Looking back, Elizabeth wishes she had dated seriously in college. The students in her selective college were smart and hard-working; she thinks she could have found a guy back then who would have been a good fit for her—both “roughly the same intelligence” and the “same nerdy personality” that she has. But her parents did not encourage her to date when she was in college or law school “because I think they just had no idea how difficult it actually would be” to date later. In fact, “they’re very surprised that I’m not married.”

What her parents—and many other parents, professors, and peers of today’s young adults—don’t know is that dating has become much more difficult now than it used to be. A new Wheatley-Institute for Family Studies (IFS) report finds that about two-thirds of young adults (22-35) who are not married but interested in marrying had not dated or dated only a few times in the last year, in part because they lack the confidence to approach the opposite sex. Another survey from Pew found that more than one-third of single young adults (18-39) are not looking to date. Trends like these help explain why a record share of today’s young adults—one-in-three—are projected never to marry.

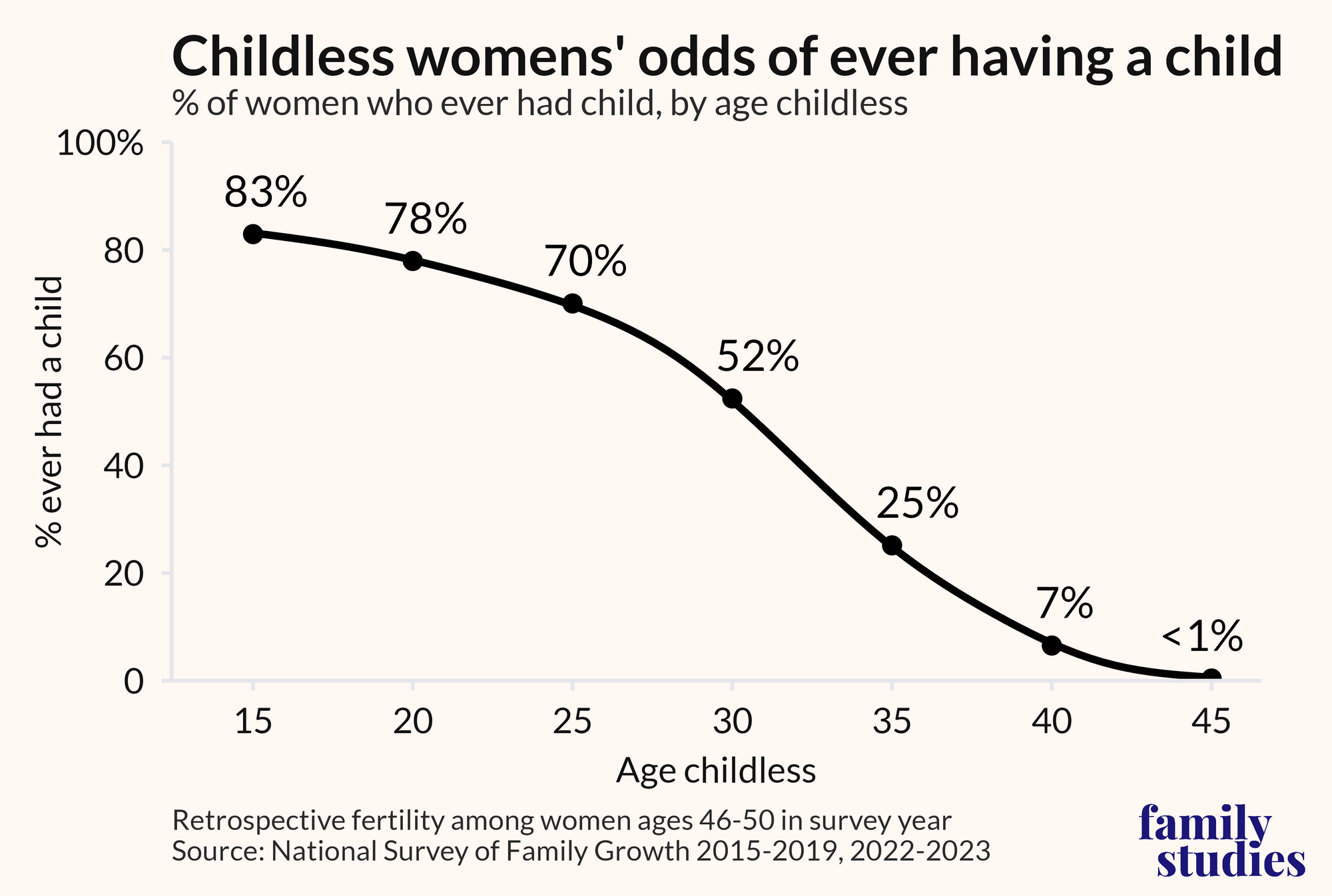

They also explain why Charlie Kirk made this provocative claim about young women’s odds of having a child: “If you don’t have kids by the age of thirty, you have a 50 percent chance of not having kids.” His comment struck even me as a stretch, and I’ve been studying the American family for the last twenty-fix years. But, again, he was onto something. An analysis of retrospective demographic data by Grant Bailey at IFS found that women who are middle-aged today and reached thirty without starting a family did indeed have only a 52 percent chance of having children. It’s true that delayed motherhood is increasingly common, and that may nudge the statistics in a slightly more optimistic direction for women reaching thirty childless. Still, the fundamental calculation remains: Cross that threshold without children, and your odds of having children fall closer to almost one-in-two.

Statistics like this can seem abstract, but they’re not for women and men like Elizabeth who are struggling to find love and get started on a family in their mid-thirties. This is even more so for the record share of never-married adults in their forties. One never-married female colleague at UVA who falls into this demographic jokingly told me that more college students need to start thinking again about the BA as the place to find a Mrs. or Mr. degree.

She’s onto something. In my sociology of family class at the University of Virginia, I tell my students that they’ll never again be surrounded by such a large pool of eligible dating prospects as they are in college. What’s more: Given the difficulties so many young adults face when it comes to dating today, I add, they should be extra attentive to seizing the manifest opportunities college presents to find a potential mate.

This is not to say there are no risks associated with twenty-something marriage or that everyone should marry their college love. The biggest risk is divorce, given that couples who marry in their early twenties are more likely to land in divorce court, in part because they are more likely to be immature. But those risks can be minimized, I also tell my students, by focusing on finding a mate who is a good friend, as well as by embracing a common faith and avoiding cohabitation. Younger couples who are religious and do not cohabit prior to marriage are less likely to divorce.

But marrying in your twenties also has upsides that don’t get enough play in today’s culture. It maximizes your odds of forging a meaningful life as a young adult, and of having the number of kids you would like to have. It minimizes the odds that your own parents’ “time as grandparents is shortened,” as Elizabeth told me. And, by lending direction, meaning, and a sense of solidarity to your life, it gives you a much better shot at succeeding in the classically American “pursuit of happiness.”

Of course, marrying in your twenties is predicated on finding the right someone. I was fortunate enough to spot the woman who would become such a friend in a UVA classroom more than thirty years ago. It took Danielle and I three years after our first date at Mr. Jefferson’s University to find our way to the altar, at the age of twenty-four. But one thing is certain: Graduate school, work, and parenthood in our twenties and thirties were immeasurably happier and more meaningful because we had marital love as the foundation of our young adult lives.

The value of a young marriage doesn’t just matter for young adulthood. It extends into mid-life. As we head into this Valentine’s Day, I’m so grateful that I did not hesitate to pursue and marry Danielle in our early twenties. I cannot imagine mid-life without her and our kids.

This is another reason that I tell my students they need not wait until thirty. If you find the right person in your twenties, don’t hesitate to commit—or risk missing what may be the most important opportunity of your life: building a marriage and family.