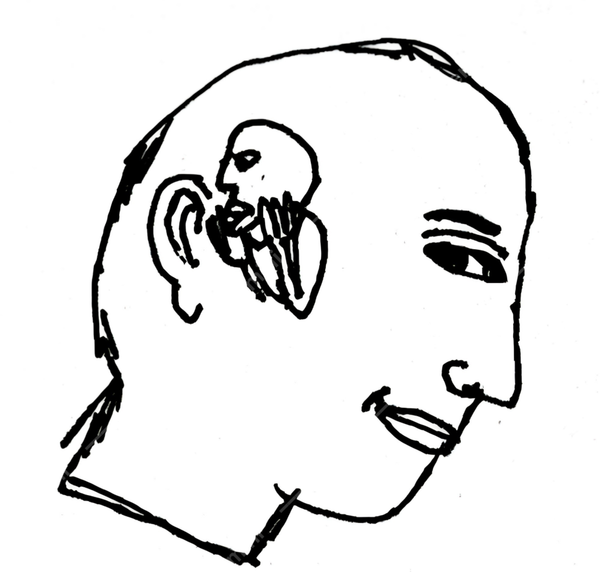

Harek, who was Hildirid’s son, whispered in the ear of King Haraldr: His trusted hersir Thorolf, hero of Havsfjord, lord of Sandnes, was a traitor. Like his father Kveldulf, he was a malcontent and rebel, and was hoarding his true fortune in secret. The king had just returned from a feast, thrown for him by Thorolf, at which he had been presented with a gift: a longship, newly carved, with its prow in the style of a dragon. It almost wasn’t so, Harek revealed. Thorolf meant to ambush you; the feast was thrown together at the very last, only when the size of the king’s retinue caught the schemers by surprise. Soon, Harek said, Thorolf would raise an army and declare himself a rival king. A dozen other courtiers attested to these facts. King Haraldr, enraged, sailed to Sandnes. There he set fire to Thorolf’s longhouse, burning his men inside, and slaughtering those who managed to break free. Thorolf himself fell in battle just a few steps from the king. His lands and duties were given to Harek and the other witnesses against him. Thorolf was remembered as a traitor and that was the story for four hundred years until the truth of Harek’s slanders were revealed by the poet Snorri Sturluson in the Egils saga Skallgrimssonar.

We do not know if in the days or weeks or centuries after Haraldr slew Thorolf, some idle rower on a raiding ship, turning matters over in his mind, ever turned to his fellows and told them, in hushed tones, that this whole story about honor and ambition stank. If you thought about it, if you put two and two together, you would see that the establishment at court feared Thorolf. There was no “hoarded treasure.” There was no planned ambush at the feast. Harek had invented the whole thing in order to seize control of his tax domains. He’d probably bribed or blackmailed the other witnesses. By the time the king figured it out, it didn’t matter. He had to help cover it up, had to stick to the official story or there’d be a rebellion by Thorolf’s kin. We do not know, either, if the other rowers rolled their eyes and called their friend a crank.

“We have always whispered, doubted, speculated, wondered.”

We do know that we have always whispered, doubted, speculated, wondered: The guards outside the door of Al-Amin, Caliph of Abbasid, who whispered that this bitter civil war with al-Ma’mun was not about the will of al-Rashid’s succession, nor who might be the child of a Persian whore, but who controlled the rich trade routes of Khurasan—it’s all about the money. The minor counts of Francia, who passed notes, uncertain in their providence, that the deus vult of Urban II was the vult of a shadowy deal between the Pope and the Emperor of Byzantium to weaken the position of the Holy Roman Emperor Otto IV. Wild rumors spread through the streets of Constantinople: the cura annonae, the grain dole, had not been stopped because of the fall of Alexandria, like the liar Heraclius claimed, but because the Basileus wanted to starve the people into servility. They’d seen the long boats loaded down with cereals arriving in the middle of the night. It was being hoarded in the palace for the fat eunuchs of the court.

Were these “conspiracy theories”? The term is often spoken but rarely understood. As we read in issue 88 of the Psychology Postgraduate Affairs Group Quarterly: “Psychologists researching conspiracist beliefs have generally avoided the task of articulating a definition, or have sketched out brief, relatively superficial definitions with the unspoken assumption that the distinction between conspiracy theories and other claims is self-evident.” But is it? Like the truth, the definition of conspiracy theory is out there, but it is slippery, elusive. Provisional answers produce unexpected holes, fresh questions, new information to consider. It’s quite easy to forget what you think you know and to find yourself far down the rabbit hole.