Imagine yourself on an Amtrak Northeast Regional train bound for New York City, rolling through the brown-and-silver marshlands of northern New Jersey. In the distance, a tall highway viaduct pinwheels gracefully down towards the Lincoln Tunnel. Over the top of a nearby ridge you see the pinnacles of skyscrapers. Manhattan is not far away.

All at once, the train is in the tunnel. Outside the train is only darkness, and you suddenly remember that a train car is a kind of room—a bright room, full of strangers. A certain shyness falls over the passengers, and their scattered conversations become quieter. Everyone is yearning together for the arrival, which will not be long now.

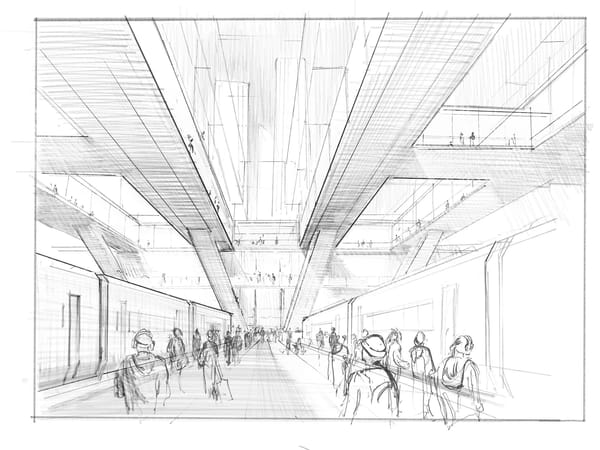

The arrival begins with light. Not the ordinary bright daylight of North Jersey, but something paler, grander, as if coming from a great height. It alternates with blocks of shadow, as if you were walking past cathedral windows. You peer out from the train. Above, there are huge bridges criss-crossing each other, hundreds of people striding to and fro across them. Above the bridges, vast skylights, and you can see people at the edges of the skylights, too, looking down at the trains below. Above them, far, far above, there are skyscrapers, impossibly high. You are in New York. The train doors open, you find the nearest escalator, and begin to ascend effortlessly, up through the light, into the great crowds at the feet of the great towers.

That last part is pure fantasy. If you have taken the train into New York’s Penn Station since 1968, the experience of coming out of the tunnel and arriving at the station is more like this: First a weird yellow light appears outside the train and you begin to see random bits of machinery and infrastructure in disorganized piles, all of it indescribably filthy. Then you start to see other trains, pressed up against a black ceiling (also filthy) that is a frenzy of pipes, ducts, flakes of rust, and horrid inhuman lights, that looks like it's simultaneously leaking, dripping, and off-gassing. When you get off the train, fetid heat, deafening locomotive noises, and an acrid smell. Your fellow passengers are crowded together on the platform, jostling and sweaty, trying to file through the narrow doorways that lead to narrow stairs. Once you've hauled yourself and any luggage you might be carrying up these stairs, trying not to crash into anyone else more than is absolutely necessary, you emerge somewhere into the station proper, a low-ceilinged warren of passageways, mezzanines, sub-mezzanines, pizza joints, and confusing signs that seem to contradict each other (they do not, in fact—it's just that there are many different routes to every point in the station).

It was not always thus. The old Penn Station, built in 1910 and designed by McKim, Mead, and White, was one of the grandest train stations in the world, modeled after the baths of Caracalla in Rome. The station was torn down in the mid-1960s, the most famous victim of an era when big stone buildings and trains were both considered to be irredeemably out of date. Its replacement was the utilitarian underground station that is still in use today. The architectural historian Vincent Scully summed up the change: “One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat.” No one who has ever arrived in the new Penn Station disagrees.

The question is what to do about it. Proposals abound. One of the most compelling is quite simple: just rebuild the old station. Unfortunately, despite the conceptual simplicity of this proposal, executing it would be extraordinarily complicated. It is not clear that it is even possible. While American society is far wealthier now than it was in 1910, changes in the labor market, construction technology, supply chains, and safety standards have made the construction of such an edifice, already a herculean task in 1910, an near impossibility in 2025. I offer a new proposal herewith, one that can actually be built, which can make the story I told at the beginning of this essay a reality.

Nostalgia for the old station often focuses on its colonnaded facade, or the coffered vaults in the main waiting room. I suspect that even more important for the passenger experience was the enormous glass roof that flooded much of the station, and the tracks themselves, with daylight. Even in photographs, it is possible to discern something of the grand, spacious quality of that light as it filtered down to the passengers below.

The essential thing is to get daylight onto the tracks again. Going through the tunnels is already a perfect setup for a monumental entry to the city. The darkness and the contraction of space even now can seem like preparations for a great ceremony. This effect is easily lost on the poor souls who pass through Penn Station regularly, because they’re used to disappointment, but if you imagine someone coming to New York for the first time, it’s not hard to see that the tunnels are like the silence before a conductor’s baton comes down at the beginning of a concert. What is needed is the first note of the symphony, which should be a sense of expansion and light. Whatever else the station does, it must offer a sense of vast space, and it must do it from the tracks themselves, not merely in part of the station—as is currently the case with Penn’s sister station Grand Central. The best way to do this is with a flood of daylight and a view up to the city above.

This can be accomplished mostly by demolition. The two floor levels between the track level and the street level are entirely unnecessary. What is needed is a single level between the street and the tracks throughout the station, as is currently the case for the Long Island Railroad concourse. This level will be a sort of lattice over the track level, with a series of east-west bridges and north-south bridges. Each of the north-south bridges will have access points via escalator to all the tracks, which run east-west. (New access points are desperately needed, track access being the only aspect in which the current station is truly functionally deficient, beyond its aesthetic and symbolic failures.) The east-west bridges will provide circulation between the north-south bridges, and can host shops, bathrooms, ticket machines, and other amenities as needed.. The gaps left between the bridges will be fully open to the tracks below, and it will be possible to look down from the bridges to the tracks.

It is through these gaps that the daylight will wash down from above. To make this work, the level above the bridges, street level, will be turned into a public square, punctuated by large glass canopies. These canopies will let in the light that filters down to the tracks, and will also be the access points into the station from the street.

These canopies will also serve as the only above-ground architecture. Their appearance will be important, but not decisive, as the main architectural effect of the station will be the space and daylight, not the specific details of the canopy design. Contemporary architects are good at designing glass canopies with a wide range of stylistic effects. Grimshaw Architects’ retro-utopian Eden Project, Thomas Heatherwick’s neo-Steampunk Bombay Sapphire distillery, Foster and Partner’s glass roof for the Dresden Hauptbanhof, and many other recent projects, could serve as precedents.

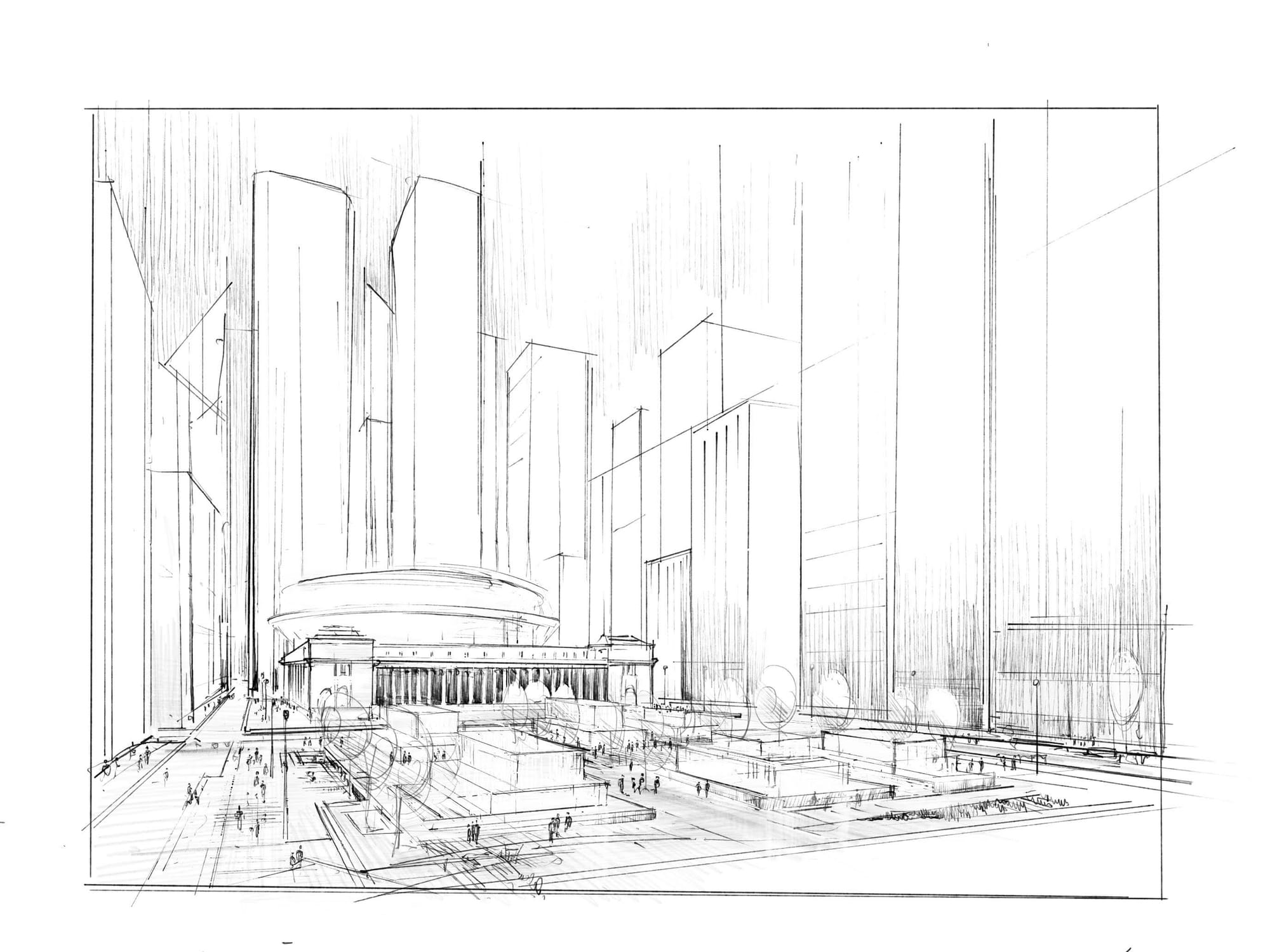

Apart from the canopies, the present footprint of the station will be given over to a public square. In fine weather, this square can serve as an extension of the station itself, with benches for waiting and storefronts along the edges. The recent pedestrianization of part of 33rd Street at the station’s northern edge provides a good example of how the square's edges can flow naturally into the surrounding city. Ideally, a renovated station would see the full pedestrianization of 33rd and 31st Streets between 7th and 8th Avenues.

On the western edge of the square, across 8th Avenue, the flattening of the current site into a square will liberate the stately colonnaded facade of the 1912 Farley Post Office building, also designed by McKim, Mead, and White, art of which now houses Moynihan Train Hall a large and pleasant waiting room retrofitted into the old building, that is, alas, quite awkwardly detached from the core Penn Station complex, readily available only to passengers who happen to disembark from the westernmost end of certain trains). The facade will serve as the natural monumental focus of the square, bracketing its entire western edge.

To the North, East, and South, the parcels surrounding the square should be radically upzoned, and rights to develop these parcels auctioned off to the highest bidder. The resulting revenue from these sales can pay for the redevelopment of the station, and revitalize the surrounding neighborhood. Locating tall buildings near transportation nodes is sensible on pragmatic grounds; aesthetically, the area would only be improved with the addition of new and taller buildings. At present some of the surrounding parcels are absurdly underdeveloped, low-rise and low rent.

One particularly tricky problemis what to do with Madison Square Garden, the largest and most important indoor arena in Manhattan, which currently broods over the top of the western half of Penn Station. Few would object to tearing down the existing arena, an undistinguished cylinder built at the same time as the new Penn Station. The difficulty is finding a new location for it.

The best solution is to relocate it exactly one block to the west, at an elevation roughly 100 feet higher. While the eastern third of the old Post Office Building has been given over to Moynihan Hall with its beautiful glass roof, the western two-thirds of the building contains only offices. Madison Square Garden should occupy this footprint instead, rising high above the current roofline, like a monumental bauble. Alterations to the Post Office Building would be purely internal. The current facade would remain untouched.

From the square, looking west, you would see first the classical Post Office facade, then, higher and further back, the new Madison Square Garden (ideally a sculptural, iconic form), and then, higher and further still, the glassy skyline of Hudson Yards. All around you, you would see New York: new skyscrapers, towering ambition, brash confidence. The effect would make for the grandest public space in the city. One would again, at last, enter the city like a god.